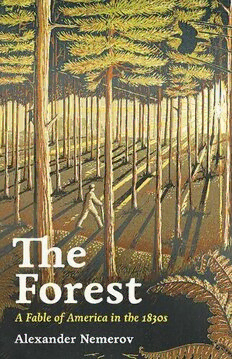

The Forest: A Fable of America in the 1830s PDF

Preview The Forest: A Fable of America in the 1830s

forest the Alexander Nemerov forest the A Fable of America in the 1830s princeton university press Princeton and Oxford the a. w. mellon lectures in the fine arts national gallery of art, washington Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Bollingen Series xxxv: 66 For Jeremi Szaniawski Shakespeare’s plays are not in the rigorous and critical sense either tragedies or comedies, but compositions of a distinct kind; exhibiting the real state of sublunary nature, which partakes of good and evil, joy and sorrow, mingled with endless variety of proportion and innumerable modes of combination; and expressing the course of the world, in which the loss of one is the gain of another; in which, at the same time, the revel- ler is hasting to his wine, and the mourner burying his friend; in which the malignity of one is sometimes defeated by the frolick of another; and many mischiefs and many benefits are done and hindered without design. —samuel johnson, Preface to Shakespeare, 1765 Contents Author’s Note ix Part One: Herodotus among the Trees 1 A Lone Pine in Maine The Town the Axes Made Hat and Tornado rush, rush, RUSH History without a Sound The Sacred Woods of Francis Parkman A Shallow Pool of Amber Grand Central Part Two: The Tavern to the Traveler 24 The Sleep of John Quidor The Dancing Figures of the Mountain Pass The Dutchman’s Diorama Menagerie The Man with the Amputated Arm A Land of One’s Own Down the Well The Song of Cold Spring The Branches Played the Man An Oak Bent Sideways Part Three: Come, Thick Night 47 Smoke and Burnt Pine Sculpting Thomas Jefferson’s Face Reading the Leaves A Meeting in the Great Dismal Swamp Part Four: Panic 60 Ere You Drive Me to Madness Lifesaver Sayings of the Piasa Bird The Death of David Douglas Part Five: Animals Are Where They Are 82 Lord of the Sod Night Vision The Cup of Life Calamity at New Garden Spiders at the Altar Moose and Stencil Encounter in a Black Locust Grove Part Six: The Clocks of Forestville 109 The Time the Peddler Fell Daybreak on Monks Mound The Clocks of Forestville Longleaf Pine and a Length of Time Shades of Noon A Trip to Bloomingdale Asylum The Lost Child Part Seven: Supernatural 145 The Actress at the Waterfall Harriet of the Stars The Glitter of the Argand Lamps A Sight Unseen at New Harmony A Statue in the Woods The Secret Bias of the Soul Deities of the Boardinghouse Triptych of the Snuff Takers The Drug of Distance Painter and Oak Part Eight: Four Greens 207 The Gasbag of Louis Anselm Lauriat Ship of Elms Pray with Me Backflip and Sky Part Nine: Three Levitations 225 The Architect’s Escape The Many Skulls of Robert Montgomery Bird Two Sisters at the Mountain House Postscript: The Shield 242 Acknowledgments 249 Notes 250 Credits 269 Author’s Note This book tells the story of many people. Sometimes they know one another, sometimes they do not. Often they go their separate ways, this person striving for one thing, that one for something else. Together they make a pattern of life at a given time in the history of the United States. The forest is a backdrop— if not always an actual setting— for what follows. Trees play an important role, but this is not a book of ecology. It portrays the dense and discontinuous woods of nation, a forest of people destroying and saving the woods and, in some way, themselves. These people are all artists in one way or another. Some are painters and poets. Others have no artistic intention. But all are creators of private and grand designs, makers of worlds in the way that this book, in telling their stories, makes the world they lived in. My artists—m y characters—a re mystics traveling paths of realization, lost in thought. The action unfolds in brief stories. Each is an episode, an impression, not an argument or claim. The reader searching for conclusive meanings will be disappointed. The book is a fable, not a history. For authoritative histories of the period, I recommend, among other books, Sean Wilentz’s The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln, Daniel Walker Howe’s What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1 848, and Charles Sellers’s The Market Revolution, 1815– 1846. Much of what follows is based on the historical record, though only some of it is true. Yet I hope that something real is revealed: a lost world of intricate relation, of human beings going about their ways, living the dream of themselves in shade and sun. —a lexander nemerov