The Federation of Khasi States: History, Epistemology and Politics PDF

Preview The Federation of Khasi States: History, Epistemology and Politics

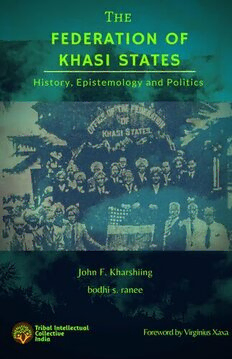

0 The Federation of Khasi States History, Epistemology and Politics by John F. Kharshiing & bodhi s. ranee The Federation of Khasi States: History, Epistemology and Politics COPYRIGHT: @2019 The authors and Tribal Intellectual Collective India COVER AND BOOK DESIGN: Subodh N.W COVER: Governor of Assam Province Akbar Hydari and the members of the Federation of Khasi States taken on 16 August 1947 in the Office of the FKS. Book edition 2019: ISBN 978-81-942059-1-3 Published in India by Insight Multi Purpose Society, Maharashtra in collaboration with the Tribal Intellectual Collective India The Tribal Intellectual Collective India (TICI) is an Imprint of the Insight Multipurpose Society (IMS). The Tribal Intellectual Collective India endeavours to promote Tribal literature and writers. It aims to further the tribal/Adivasi discourse through publishing academic and scholarly works. It is driven by a sincere desire to deepen a ‗perspective from within‘ in Tribal history and theory. This book series comes under the Dialogical Historiography Project of the TICI and attempts to propel the ‗writing of histories from within‘ around a new framework called Decolonial-Historical Approach. No part of this book may ne reproduced, retrieved or transmitted in any form, by any means without the prior permission of the copyright holders. For more information: www.ticijournals.org. Dedicated to Paiem (Dr.) Balajied Sing Syiem and all the Khasi Chiefs from Dorbar Shnong, Dorbar Raid and Dorbar Hima Contents Foreword by Virginius Xaxa i Preface viii Introductory Note: Laying the Context and Frame Part I 1 Part II 11 Part II 19 The Khasi Chiefs Section One Before 1835 38 Section Two From 1836 to 1862 95 Section Three From 1863 to 1913 111 Section Four From 1913 to 1946 163 The Federation of Khasi States Section Five From 1923 to 1949 176 Section Six From 1949 to 1998 237 Section Seven From 1999 to 2017 278 Additional Resources 471 Foreword The Federation of Khasi states is a study of the traditional political system prevalent among the Khasis of Meghalaya. It provides an important site for interesting theoretical discussions on the nature of the state or political system in a traditional tribal society and its engagement with the larger world. Such studies have remained unexplored in the context of tribes in India. The monograph is a pioneering venture in this sense. The conceptual distinction between state and society emerged in European thought in the 18th century. Before this period, the term state and society were in use but there was no distinction made between the two. Writing on the state was considered as writing on society and vice versa. Since the making of the distinction, the state has been a subject of much engagement in European thought and scholarship. The scholarly concern with the state has spread to other parts of the world as well. The prominent role the state has come to play in the lives of the people in modern times may be the reason for such attention on the state. Needless to say, much of the concern has been with the modern state. The writings on the state in social science literature concern with various aspects of the state. Some of the key aspects of concern has been with the nature, role, and character of the state. Since the distinction between state and society, there has been much attempt to delineate as to what the state is. The state has thus come to be thought of as an institution that is concerned with the maintenance of order in society and to this end, it has the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force. Further, the modern state has been studied from several angles that broadly fall into three categories. One of these sees the state as an independent and autonomous entity with its own rules of action. Others see it as tied to the interests of the dominant class but within this too there are variants i of thought. Then there are still others who regard the state as a partly independent force that the different political interest groups may influence via the democratic political process and mobilization at different points of time. Although a lot is written about the nature and character of the modern state, not much is known about the nature of the state in historical societies and much less on societies described as tribes by social anthropologists. The value of the present monograph lies in this endeavour. This is one of the rare studies which attempts to study traditional political systems in the context of tribes in India. The study describes the system prevalent among the Khasis as the state. There have been some studies in the context of tribes including Northeast India that have addressed the question of state formation before tribes were incorporated into the colonial state. The pre-colonial state here is referred to the principality or kingdoms that have emerged among tribes before the entry of the British rule. The traditional Khasi political system does not however fall in the genre of the kingdom. These kingdoms were predominantly territorial entities. In contrast, the traditional political system prevalent among the Khasis, though had a territorial jurisdiction, was not autonomous of the institutions of kinship, the hallmark of tribal society. It may not be out of place here to situate the study of tribes in Africa that have been studied from the lens of the state. In keeping the focus on state, tribal societies in Africa have been classified into state and stateless societies. Tribes with a distinct and centralized authority for maintaining peace and order in the society have been described as societies with state and others as stateless societies. However, tribes even without state-like institutions did maintain order in society. In bearing this in mind, the distinction has been drawn between the state and political system in understanding the maintenance of peace and order in society. The tribes may not have the state but they did have a political system. Hence in the understanding of the polity in tribal society, often the term political system has been preferred to the use of the term state. Thus the study of the Khasi ii state can be the site of an interesting theoretical discussion on the aspects of the political systems of the tribal society. The Khasi traditional political system is strikingly different from other tribal traditional political systems of tribes in Northeast India including its matrilineal tribal communities such as the Jaintias and Garos in the state of Meghalaya. Most tribes in Northeast India had a political system that did not go beyond the village. At the level of the village, the political system was either visible in the institution of the village council comprising the elders of different clans in the village. The council was headed either by a headman or a chief who was either autocratic or democratic in the sense he took decisions on the issues in consultation with the members of the council. The Khasis unlike other tribes had developed a political system that went beyond the village. That is, a number of villages formed a larger configuration or confederation which was referred to by distinct names; Syiem, Lyngdoh, Wahadadar and Sirdar. The territorial structure so developed was headed by a person chosen by the assembly of the elders who comprised of the village‘s headman of the larger territorial unit. In this design of the political, the Khasi political system very much resembled the manki system of the Mundas, manki-pir of the Hos, paraganait of the Santhals, and parha of the Oraons. It is somewhat intriguing that except for the Oraons all those tribal groups that have such political systems belong to a linguistic family ( Austro-Asiatic) as the Khasis. The Oraons as per the existing linguistic classification belong to the Dravidian linguistic family. The Oraons and Mundas have been living side by side for centuries and it is possible, they may have adopted the system from the Mundas. Of course, this needs further investigation. Notwithstanding such commonalities, there seems to be a difference. Unlike the Mundas and Santhal who had two tiers system, the Khasis had developed the system even into the larger unit, that is, of syiemship (chiefship). The traditional Khasi political iii systems comprised of three interconnected sets of institutions viz shnong (village), Raid (elaka), and syiem (chiefship). Each of these systems was intricately related to clans at the appropriate level. Hence unlike the other states or political system, which were primarily territorial, viz primarily centered around the territory and its inhabitants without any other social institution, the Khasi political system at each level was intricately connected with the clan system. This means that states were not autonomous as it was thought about, rather it was related intricately to the kinship system. How to explain the distinct feature of the Khasi political system is difficult to explain. Probably this may have to do with ecology, demography, and technology combined with the kinship. While the role of ecology, technology, and demography is yet to be ascertained, the role of the kinship and its relation to the Khasi political system seems certain. Its presence is visible at the village, raid, and more importantly at the state or syiemship. Not only is it related to kinship but it is also intricately related to religion. Thus, the Khasi state needs to be explored in the context of kinship and religion. As to how the Khasi political system would have evolved in the absence of intervention by the British in the Khasi Hills territory is a hypothetical question and can only be speculated. The fact is that the intervention by the British did change its route. This is evident in course of events that the Khasi political system had to go through following the winds of change that colonial India including Northeast India was going through since the 1930s. The emergence of the Khasi National Dorbar in the 1920s and later in the 1930s into the Khasi States Federation was an attempt to rethink their political status at these backdrops. Its agenda was to work out its future in the event of the shaping of a new political configuration in British India. The tribal communities on the eve of India‘s independence were located in different kinds of political and administrative arrangements. The large size of tribes formed part of the princely states and hence was not part of British India. iv The rest was part of British India but they were organized around different administrative arrangements such as the excluded and partially excluded areas following the Govt. of India Act of 1935. At the eve of independence, the Khasi Federation of states aimed at a different route to their participation in the Indian union. This was evident in a memorandum submitted to the Viceroy, Lord Willingdon who visited Shillong in 1933. Its stated objective was to act as a representative and executive body for all the 25 Khasi States and put forward a claim for securing greater judicial power from the British. The chiefs wanted more administrative powers from the government and the transference of some departments under the Deputy Commissioner to the management of the states. It also carried on negotiations with the government for recognising the KSF as the body to speak for the Khasi states when any alteration of policy and administration was planned. It signed the Instrument of Accession (IoA) and Annexed Agreement (AA) with the Dominion Government of India following which a Khasi States Federation Court was set up. Also, some departments of Administration were opened. The Federation using powers prescribed under the IoA and AA operated like a government. The Federation of Khasi States had its own flags with 25 stars (representing 25 States) side by side with the Indian National Flag. As per the Indian Independence Act 1947, two dominions were formed; India and Pakistan. Many princely states signed the Instrument of Accession (IoA) and the Instrument of Merger with the Indian Union. The Khasi States are the only native state within the India Union who did not sign the instrument of merger, although all of the 25 Khasi states did sign the IoA in phases either individually or collectively. The first was signed on15 December 1947 and the last on 19 March 1948. The last to sign was the Nongstoin state. It did so only at the threat of an army contingent which was sent to pressurise the chief. v