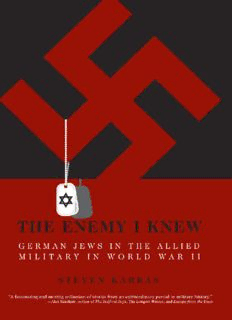

The Enemy I Knew - German Jews in the Allied Military in World War II PDF

Preview The Enemy I Knew - German Jews in the Allied Military in World War II

THE ENEMY I KNEW GERMAN JEWS IN THE ALLIED MILITARY IN WORLD WAR II STEVEN KARRAS For the refugees of Nazism who wore the uniform of the Allied Armed Forces during World War II If we mean peace by slavery, then nothing is more wretched. Peace is the harmony of strong souls, not the fightless impotence of slaves. —Baruch Spinoza CONTENTS Prologue Foreword Preface Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1 Siegmund Spiegel Chapter 2 Jerry Bechhofer Chapter 3 Adelyn Bonin Chapter 4 Eric Hamberg Chapter 5 Bernard Fridberg Chapter 6 Fritz Weinschenk Chapter 7 Peter Terry Chapter 8 William Katzenstein Chapter 9 Karl Goldsmith Chapter 10 Henry Kissinger Chapter 11 John Stern Chapter 12 Ralph Baer Chapter 13 Bernard Baum Chapter 14 Harold Baum Chapter 15 Edmund Schloss Chapter 16 Walter Reed Chapter 17 Manfred Steinfeld Chapter 18 Jack Hochwald Chapter 19 Norbert Grunwald Chapter 20 Eric Boehm Chapter 21 Fred Fields Chapter 22 Peter Masters Chapter 23 John Brunswick Chapter 24 Otto Stern Chapter 25 Kurt Klein Chapter 26 Harry Lorch Chapter 27 Manfred Gans PROLOGUE Dearest ones all, A collective letter is coming your way, one that will be of particular interest to all the Frankfurters, relatives and friends and foes alike. I have finally fulfilled the nightmare which followed me in my dreams, just like it followed you perhaps. I was there. Captain Speckman, Brown, Wolf and I took the jeep this morning and rode. I heard the familiar dialect and I saw familiar sights. Slowly places and names came closer. I can’t deny that my heart was beating a little faster. There was Frankfurt, or was it? On we went slowly, and I tried to absorb every memory. The tower of the Dom was still there, but the church belonging to it was only a skeleton, that is completely uncovered, so that the tower of the Dom stood all alone. The Schauspielhaus has disappeared; there is a tremendous hole in the ground where it used to be, only part of the stage-house has still some walls standing. The familiar sight along the Main River looked changed, it looked familiar and then again it did not. Whatever houses are still standing along the river’s edge, are no more houses, just empty shells. The Gestapo Headquarters on Lindenstrasse is down, so are most of the houses there. We turned slowly into Kaiserstrasse and towards the Rossmarkt. This used to be a fairly long block. But now it seems awfully short because between Frankfurter Hof and Rossmarkt all houses are gone, every one of them, to both sides of the street there is space filled with rubble. You can’t walk on the sidewalks, they are roped off or filled with stone, not a single building is even as much as inhabitable. Most of the streets are impossible to pass, by foot or jeep. Then we went to Wiesenau to look for Oma’s house. It is not there any more, don’t worry over it, mom, Oma did not live to see the day. I went into a few houses and asked a few people for her name, it seemed to me she lived on number 54, but nobody knew her. She is not alive any more, I’m sure of that, mom; she is better off that way, believe me. Our house, number 53, must have had a direct hit, because it is now a pile of twisted girders, stones and dust. The iron front gate sticks out from the end of the letterbox [which], strangely enough, lies on top of the pile. Just one wall is standing. The “house” looks as if somebody had taken a knife and cut it straight down, throwing everything on one big pile, but leaving the rear wall standing. It was very silent in Gruenstrasse, not a soul, the wind was waning some of the hanging window shades and made a weird noise, as if the bones of old times were shuddering, bringing back memories. We traced our steps back to the synagogue. Strangest sight of all: It is complete, absolutely undamaged, copula and all, as if it was ready to open for services any moment. The houses facing it [are] all damaged, empty, burned out, but our synagogue is untouched. Of all things where else could God’s unbelievable justice be more evident than here? It is hard to describe the emotions that went through me, it’s just like going home after many years and looking for the people you used to know and all you find is their grave. That’s what Frankfurt is today, a graveyard, a vast terrible graveyard, a sign of Divine justice, of retribution, a sign of God’s wonderful ways to lead us away from the Sintflut [deluge] before it could engulf us. Where else and where more would we have reason to sink down on our knees with tears in our eyes? I almost had them, and thank Him for all he did for us, that he led us away from it all to this land of Liberty, the United States of America. And where else could it be that I, born in that town, would return after so many years, as an Officer of a conquering Army. I felt as if today I was the safe keeper of the many thousands of Jews of Frankfurt or Germany that came with me together in spirit to see what Justice eternal does. Walter Rothschild 175th Regiment, 45th Division United States Army FOREWORD Almost two decades ago when we began working on the final film for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s permanent exhibition, we revisited the riveting testimony of Gerda Weissman Klein and her husband, Kurt. Gerda was a Holocaust survivor who, after a death march of many months, was liberated in the Czechoslovakian city of Volary. Her liberator was an American GI lieutenant named Kurt Klein. When telling the story, Gerda said, “I looked into his eyes and said, ‘I must tell you something … we are Jews.’ And for what seemed like an eternity he stood there and then he answered, ‘So am I.’” Gerda weighed seventy-eight pounds, her hair was white, and she hadn’t had a bath in years. Yet Kurt and Gerda grew to love one another, married, and raised children and grandchildren. In the testimony Gerda’s story seemed primary. The primary text of the Holocaust is the story of the victims, and the best way to understand their plight—to enter what we now call l’univers concentrationnaire—is to heed their words orally and even visually. Only thus can we understand, only thus can we come close to understanding. And yet that is not the only story—the only narrative—of the Holocaust. Kurt was a German Jew who found refuge in the United States and sought with all his limited power to have his parents join him in freedom. He was unsuccessful and they were murdered at Auschwitz, according to the best of information that he could find. That part of his story was covered in the PBS series America and the Holocaust. Kurt was a German Jew who returned to Germany, the land that had killed his parents, had oppressed him, and was only too happy to see him leave, as forced emigration was the first of the German policies toward the Jews. Mistakenly, I had not understood that Kurt, too, had a powerful story to tell, a story of not only victimization, death, and destruction, but also of exodus and return, empowerment and vengeance, of turning the tables on his former countrymen. He was the Jew as warrior, the Jew as conqueror, the Jew as liberator. More mistakenly, I had presumed that his was an isolated story until I met a young and talented filmmaker named Steven Karras. Steve was working on the film About Face: The Story of the Jewish Refugee Soldiers of World War II, which told the story of the many men and women who shared a common past with Kurt, whose journey resembled his own. Cast out of Germany, often leaving their parents and siblings behind, they found their way to the United States and England where their adjustment was painful. They were regarded as immigrants in countries that did not welcome immigrants. When the war began, they were regarded as Enemy Aliens and were suspected of being “fifth column” spies for the motherland. For a time, it was beyond the comprehension of the U.S. and British governments that Jews deserved a different category. They had not only left their homeland, their homeland had left them. They had every reason to fight Nazi Germany—every possible motivation. They understood that World War II was a matter of life and death, good versus evil, a true clash of civilizations. At stake was the character of civilization. Then, wonder of wonders, the governments of the United States and the