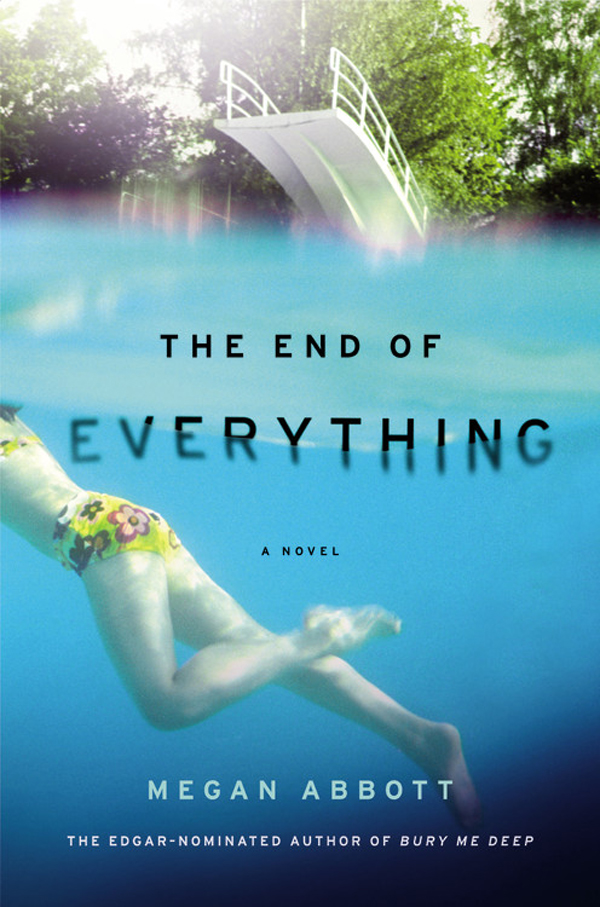

Download The End of Everything: A Novel PDF Free - Full Version

Download The End of Everything: A Novel by Megan Abbott [Abbott, Megan] in PDF format completely FREE. No registration required, no payment needed. Get instant access to this valuable resource on PDFdrive.to!

About The End of Everything: A Novel

Amazon.com Review<p>Thirteen-year old Lizzie Hood and her next door neighbor Evie Verver are inseparable. They are best friends who swap bathing suits and field-hockey sticks, and share everything that's happened to them. Together they live in the shadow of Evie's glamorous older sister Dusty, who provides a window on the exotic, intoxicating possibilities of their own teenage horizons. To Lizzie, the Verver household, presided over by Evie's big-hearted father, is the world's most perfect place. <br></p><p>And then, one afternoon, Evie disappears. The only clue: a maroon sedan Lizzie spotted driving past the two girls earlier in the day. As a rabid, giddy panic spreads through the Midwestern suburban community, everyone looks to Lizzie for answers. Was Evie unhappy, troubled, upset? Had she mentioned being followed? Would she have gotten into the car of a stranger? <br></p><p>Lizzie takes up her own furtive pursuit of the truth, prowling nights through backyards, peering through windows, pushing herself to the dark center of Evie's world. Haunted by dreams of her lost friend and titillated by her own new power at the center of the disappearance, Lizzie uncovers secrets and lies that make her wonder if she knew her best friend at all.<br></p><p>Author One-on-One: Megan Abbott and Sara Gran <br></p><p>In this Amazon.com exclusive, author Megan Abbott is interviewed by Sara Gran (<em>Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead</em>) about <em>The End of Everything</em>.</p><p>Sara Gran: <em>The End of Everything</em> shares common themes with your previous four novels, yet stands out as a departure—it takes place in the 1980s (your other novels took place before you were born), the narrator is 13 years old (your previous narrators were adult women), and it takes place in the suburbs (as opposed to the urban settings of your other books). How is <em>The End of Everything</em> the same? How is it different?</p><p>Megan Abbott: I wanted to try something new, to shake things up for myself. To move out of the world of nightclubs, racetracks, movie studios and, most of all, to move out of the past, worlds I never knew. When I first started writing, though, everything felt foreign, puzzling. I didn’t know if I could adapt my style to this new setting and time period. My past books were so influenced by Golden Age Hollywood movies and that heightened style. And I’d done this foolish thing, giving myself a 13-year-old girl as my narrator. But as I wrote, I just had this revelation that, for most 13-year-old girls, life is dramatic and the stakes feel dramatically high. It’s all desire and fear and longing and disillusion. Everything feels big and terrifying and thrilling. And my past books, I see now, are so much about women feeling trapped and seeking a way out, at any cost. And feeling trapped, and wanting out, is very much the state of being 13.</p><p>Gran: What were the body of influences you drew from in creating this character and this story? Lizzie, your narrator, is a bit of a girl detective, uncovering secrets about her placid suburban town--were you a Nancy Drew fan?</p><p>Abbott: I never intended Lizzie to be such an active agent in the book. My original thought was she would be a somewhat passive observer. But, as she grew in my head, she began to want things, and then she sort of took over. While I don’t think I precisely had Nancy Drew in my head, I was a voracious reader of mysteries as a kid and I do think there’s a natural affinity between writers and detectives (and I don’t have to tell you this, in light of all the magic you cast with your detective in <em>Claire De Witt and the City of the Dead</em>). To me, that link is a desire to look in places you’re not supposed to. To be a voyeur. And, as with many voyeurs (and detectives), you can only peek so long before you want "in." Which is the life of most 13 year olds anyway, isn’t it? <em>I see the adult world. I want "in."</em></p><p>Gran: How did you get back into the mind of a 13-year-old girl? Or is there a part of we adult women that has never left?</p><p>Abbott: I’m alarmed at how natural it felt. I’ve heard it said that we’re all arrested at a certain age, and for me it’s 13, which is probably why I landed at that age. But I think it’s an especially powerful age for girls. It’s the moment you peer with widest eyes into womanhood, or are flung there. It’s an age of constant push-pull, wanting to leap forward and yet often retreating in the face of real adulthood, and the price of it. I think many women look back on that age as the moment of great anticipation and often painful revelation.</p><p>Gran: To what degree, especially compared to you other books, is <em>The End of Everything</em> autobiographical?</p><p>Abbott: In terms of time and place, it’s definitely lifted straight from my growing-up years in Grosse Pointe, Michigan in the early 1980s. Before, I always wrote as an escape, a fantasy exercise to enter these shimmering, foreign worlds. My own world felt pretty mundane, not worthy of such an adventure. But somehow, maybe it was the flush of nostalgia, I was able to crawl my way back into some long-lost feeling from my childhood. That feeling of possibility, mystery, risk that suffuses all your surroundings. Also, I’m now at the age where the 1980s seems like a lost era. And I’m a sentimentalist, of course!</p><p>Gran: Tell me a little about the suburbs, especially the suburbs where this book takes place, a fictionalized version of Grosse Pointe? What is it that we love and hate so much about these liminal spaces (not urban, not rural)? Why do some of us have something like a fear of the suburbs (as I do!)? </p><p>Abbott: I love that you, a Brooklyn girl, could feel that way! I do think of suburbs as “halfway” places because it suggests a sense of complication and mystery when I think the rap they get is that they are places of conformity or hypocrisy or tedium. I think they occupy this strangely contradictory place between utter hidden-ness and this sense of vivid exposure. In the Midwest, at least, it’s impolite to poke your nose in your neighbor’s business. At the same time, there’s something unbearably intimate about them. Because of the way many suburbs of my era were designed, as kids you would end up running through each other’s backyards, hiding out in the basement, hearing all the sounds in the upper floors, uncovering secrets. So there’s this tug of war, the instinct to protect oneself, to hide one’s desires or sorrows and the simultaneous desire to reach out, to pry, to touch each other, to connect. That tension is palpable, fascinating. </p><p>All that easy mockery of the suburbs drives me crazy. To me, they’re places of yearning, which is maybe true of all places. </p><p>Gran: Throughout the course of <em>The End of Everything</em>, Lizzie uncovers secret after secret about her placid town. What role do secrets, in general, play in our lives? Are they gifts, treasures, curses, or burdens? </p><p>Abbott: I think that being 13 is in many ways like an endless process of revelation, and disillusionment. You carry all these ideas of the world, and yourself, and in many ways they all get punctured, one by one. But then somehow you manage to build new ones up. And you start to carry your own secrets, which I guess Lizzie will too. </p><p>Gran: You’re known for, among other things, pushing the boundaries of genre definitions. While your previous books fit well into the “crime” genre, they also contain elements of literary fiction, historical fiction, and mystery. Where does this new book fit in, both in terms of genre in general and in terms of your own list? Is genre relevant to you as a writer—does thinking about these categories help or hinder you as you work? </p><p>Abbott: My impulse is to say I don’t believe in genre distinctions. But I guess I’ve come to think that all novels are mysteries. Reading them, you are always that detective/voyeur, peering in, sifting through its secrets, sometimes wanting to enter the story itself, to sink yourself into those worlds. I admit, I love that John Gardner quote: all stories have one of two plots: someone goes on a journey; or a stranger comes to town. Sometimes both. Usually both.</p><p>Gran: I find that for me, every book I write leads naturally into the next on—every book is almost like a bus or a train that takes me right where you need to go to catch the next bus—i.e., to write the next book. So what have you been working on since <em>The End of Everything</em>? How did <em>The End of Everything</em> lead you to the next book? </p><p>Abbott: I love that bus analogy. That’s exactly how it feels, like the seed of the new book is sown at the very end of the last one, though I never know how it got there. My next book, <em>Dare Me</em>, comes directly from writing about girls’ field hockey in <em>The End of Everything</em>. It’s set in the world of high school cheerleading. The ferocity of that sport, the way it unleashes this inner rage, fascinated me. I see something similar lurking in cheerleading. It’s no longer dancing and pompom shaking. It’s rather dazzling and frequently death defying and it speaks to the dark and bold nature of girls, aspects of themselves that too often remain hidden. In cheerleading, it’s given full reign. Which is something to see.</p><p><em>Megan Abbott photo by Drew Reilly</em></p>Review<p>Praise for Megan Abbott:<br>''Word for word, pound for pound, Megan Abbott delivers more than any writer I know. . . She is simply one of the most exciting and original voices of her generation.'' -- Laura Lippman, <em>New York Times</em> bestselling author<br>''Abbott turns the stuff of sensational confession magazines into a rich meditation on the unclouded depths of the soul.'' --<em>New York Magazine</em></p></br></br></br></br></br></br>

Detailed Information

| Author: | Megan Abbott [Abbott, Megan] |

|---|---|

| Publication Year: | 2011 |

| ISBN: | 316097799 |

| Language: | other |

| File Size: | 0.5902 |

| Format: | |

| Price: | FREE |

Safe & Secure Download - No registration required

Why Choose PDFdrive for Your Free The End of Everything: A Novel Download?

- 100% Free: No hidden fees or subscriptions required for one book every day.

- No Registration: Immediate access is available without creating accounts for one book every day.

- Safe and Secure: Clean downloads without malware or viruses

- Multiple Formats: PDF, MOBI, Mpub,... optimized for all devices

- Educational Resource: Supporting knowledge sharing and learning

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it really free to download The End of Everything: A Novel PDF?

Yes, on https://PDFdrive.to you can download The End of Everything: A Novel by Megan Abbott [Abbott, Megan] completely free. We don't require any payment, subscription, or registration to access this PDF file. For 3 books every day.

How can I read The End of Everything: A Novel on my mobile device?

After downloading The End of Everything: A Novel PDF, you can open it with any PDF reader app on your phone or tablet. We recommend using Adobe Acrobat Reader, Apple Books, or Google Play Books for the best reading experience.

Is this the full version of The End of Everything: A Novel?

Yes, this is the complete PDF version of The End of Everything: A Novel by Megan Abbott [Abbott, Megan]. You will be able to read the entire content as in the printed version without missing any pages.

Is it legal to download The End of Everything: A Novel PDF for free?

https://PDFdrive.to provides links to free educational resources available online. We do not store any files on our servers. Please be aware of copyright laws in your country before downloading.

The materials shared are intended for research, educational, and personal use in accordance with fair use principles.