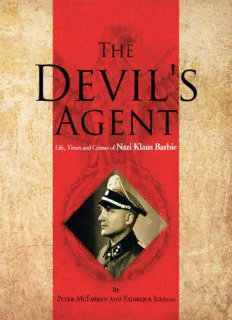

The Devil's Agent: Life, Times and Crimes of Nazi Klaus Barbie PDF

Preview The Devil's Agent: Life, Times and Crimes of Nazi Klaus Barbie

PETER MCFARREN and FADRIQUE IGLESIAS Copyright © 2013 by Peter McFarren and Fadrique Iglesias. 137950-MCFA ISBN: Ebook 978-1-4836- 5479-9 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Rev. date: 12/20/2013 To order additional copies of this book, contact: Xlibris Corporation 1-888-795-4274 www.Xlibris.com [email protected] CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS PREFACE CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 4 CHAPTER 5 CHAPTER 6 CHAPTER 7 CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER 9 CHAPTER 10 CHAPTER 11 CHAPTER 12 CHAPTER 13 CHAPTER 14 EPILOGUE ANNEX 1 ANNEX 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY ABOUT THE AUTHORS END NOTES This book is dedicated to the victims of genocide, hate crimes, and discrimination and the advocates for righteousness who fight to bring to justice the persons and institutions responsible for those crimes. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Devil’s Agent: The Life, Times, and Crimes of Nazi Klaus Barbie has its origin in 1980, when right-wing military and civilian groups funded by cocaine traffickers and organized with the support of Nazi Klaus Barbie took power through a coup d’état, riding roughshod over the most basic standards of human and democratic coexistence. The story of Klaus Barbie, however, has its origins in Europe in the 1930s with the rise of National Socialism, totalitarianism, Nazism, fascism, and religious and ethnic hatred that led to the Holocaust, World War II, and one of the darkest chapters in the history of humankind. Trying to grasp, understand and present nearly sixty years of Barbie’s life and its historical, social, and political context would not have been possible without the support of many friends and family members who contributed in numerous ways to making this book a reality. We wish to thank the persons and institutions who shared their knowledge and experience with us—in many cases painful memories—about the events described here. John Enders, a journalist friend and colleague in the 1980s, played a key role in preparing the articles published during the government of General Luis García Meza that served as the foundation for this book. We also wish to thank and recognize the following people for their support in the past and present, between 1980 and 2012, in clarifying the violent events that have continued to occur after World War II. Among them is Mariano Baptista, who, as editor of the La Paz newspaper Última Hora, helped gather information about neo-Nazis and Nazis operating in Bolivia. A special thanks to our families, especially Mela Aviles-McFarren, Mónica Tejada, Valeria and Daniela McFarren, Ana Maria Mendizábal, Begoña Iglesias, Augusto Iglesias, Lisa Polgar, Henry Polgar, Jill Aviles, Pieter DeWitte, and Neal Piper. Many thanks to Alan Shave, a former British diplomat who lived through many of the periods described in this book, for his help in translating the book from Spanish to English; Bonnie Miller, who played a key role in editing the English version and offered many ideas that strengthened the book considerably; Augusto Iglesias and Connie Echazu Bedregal who helped edit the Spanish version; Douglas McRae, Mark Frautschi, David Atkinson, Lisa Polgar, and Henry Polgar who reviewed the English text of the book and made important comments, and John Enders who wrote the preface. This book included interviews over a period of thirty years with Álvaro de Castro, Gustavo Sánchez Salazar, Beatrix Ertl, Hernán Siles Zuazo, Helena Abuawad, Father Gregorio Iriarte, Herbert Kopplin, Werner Guttentag, Jaime Aparicio, Cayetano Llobet, William Walker, Michael Vigil, Carlos Soria Galvarro, Jaime Paz Zamora, Roberto “Roby” Suárez Jr., Ed Schumacher, Maribel Schumacher-Villasante, Eduardo Gil de Muro, Rafael Sagarnaga, Alfredo Irigoyen, Peter Hammerschmidt, Gastón Velasco Carrasco, and other experts who preferred to remain anonymous. This project was made possible through the support of a Kickstarter campaign that attracted 104 supporters without whom this book would probably not have been published. We are also grateful for the generous support we received from Jill Aviles, Dr. Jerome Dancis, Betsy Ruderfer, Emil Ruderfer, Virginia Watkin, Petrus and Godelieve, Alfonso Tejada, John Newman, Anita Bhatia, Bryan Aviles, and Lynnwood Farr. Figure 1. Contact sheet of photographs taken by co-author Peter McFarren of Klaus Barbie’s documents and personal photos in 1983 shortly after he was arrested and expelled from Bolivia. PREFACE One afternoon in mid-1982, Luis Arce Gómez, the interior minister in Bolivia’s right-wing military dictatorship led by General Luis García Meza and formerly the regime’s dreaded head of army intelligence and its secret paramilitary police, left his office for a ceremony at the army’s Estado Mayor, or general staff headquarters, inside the Miraflores army building in central La Paz. It was a ceremony closed to the public and the press and included all then-current officials of army intelligence (known as G-2) as well as past officials who had served during the decades following World War II. I had just finished interviewing Arce Gómez, and he invited me to accompany him. The event at army headquarters was to decorate an ailing septuagenarian general for his many years of work in the country’s intelligence apparatus. The chiefs of Bolivian intelligence and all its branches were there, as were several less presentable creatures who normally never left the basement of the Interior Ministry, where the torture rooms were located. Klaus Barbie, known in Bolivia as Klaus Altmann, was a guest of honor at this event. Barbie’s presence in the country and his role in advising Bolivia’s military and intelligence officers in interrogation techniques and other practices were widely known and had been for years. He was of great interest to the Nazi hunters in France and Israel. Arce Gómez introduced Barbie to me as “my so-called instructor.” Then Barbie began talking about the allegations that he had committed crimes against humanity during the time he headed the Gestapo unit in Lyon, France. He ranted against journalists who were attempting to expose him to international publicity, including several who he said had cheated him out of book rights or had otherwise hoodwinked him. He talked openly about his connections to other former Nazis living in the Southern Cone region of South America without naming them. It was clear then that Barbie felt no remorse for his wartime actions. “I was a man of war in a time of war,” he told me. The personal affection and close professional ties between Arce Gómez and Barbie were clear. They had worked together closely over the years, particularly after the military seized power in a July 1980 coup d’état and during the months of severe and brutal repression against Bolivia’s labor unions, campesino and leftist political leaders and journalists that followed. Everything comes to an end, however. Eventually, Barbie lost the protection afforded him by his friends in the Bolivian military. At the end of 1982, a liberal democratic regime returned to power in Bolivia, and the military leaders who had led the coup, including Arce Gómez and García Meza, were disgraced and eventually jailed. The rest of the army returned to their barracks where they have remained. All of a sudden, Barbie had nowhere to hide and no one to hide behind. The world knew who he was and where he was, and he had no one to protect him any longer. Barbie, after World War II, had entered first Argentina and later Bolivia with false documents under the Altmann name, and he lived for many years in relative prosperity and comfort. By the 1970s, however, largely due to investigations by the couple Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, his real identity and whereabouts became known. France first requested his extradition from Bolivia in 1973. Today, Barbie’s horrendous crimes during the war as a Gestapo Nazi officer, his work for U.S. and West German intelligence agencies, his ties to right-wing military dictatorships in South America and the thugs who ran them and to the illicit trafficking in cocaine have all been exposed. It has always astonished me that Barbie (and other Nazis) lived freely and openly for so many years in South America and that even after he was unmasked and France had requested his extradition, it still took a decade to bring him to trial. It wasn’t until 1983 that he was finally returned to France, where he was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison and where he died a pathetic old man in a prison cell in 1991. Barbie’s ties to military leaders in Bolivia had first paid off during the 1971-78 regime of General Hugo Banzer Suárez, himself a descendant of German immigrants. Banzer ruled Bolivia as an ironfisted, anticommunist dictator. Not surprisingly, France’s extradition request was denied in 1974 by Bolivia’s military-appointed Supreme Court. It ruled that Barbie could not be extradited because he was a Bolivian citizen, even though it had clearly been shown that his citizenship was fraudulently obtained. During the extradition proceedings, Barbie spoke to the local press and seemed unfazed by the possibility that he might lose his freedom or his comfortable place in Bolivian society. And comfortable it was. During the 1970s and early 1980s, he was regularly seen walking the streets of La Paz, sipping coffee at his regular corner table at the Club La Paz with a bodyguard and friends. After his

Description: