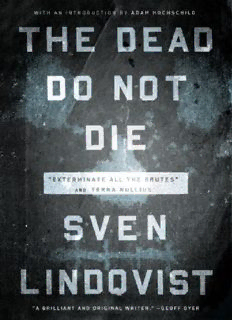

The Dead Do Not Die: "Exterminate All the Brutes" and Terra Nullius PDF

Preview The Dead Do Not Die: "Exterminate All the Brutes" and Terra Nullius

Sven Lindqvist has published thirty books, including The Skull Measurer’s Mistake and A History of Bombing (both available from The New Press). He holds a PhD in the history of literature from Stockholm University, an honorary doctorate from Uppsala University, and an honorary professorship from the Swedish government. He lives in Stockholm. Adam Hochschild is the author of seven books, including King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa and Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. Joan Tate (1922–2000) was an award-winning translator of more than two hundred books, including works by Ingmar Bergman, Kerstin Ekman, and Astrid Lindgren. She was a founding member of SELTA, the Swedish-English Literary Translators’ Association. Sarah Death is a translator, a literary scholar, and the editor of the UK-based journal Swedish Book Review. She won the Bernard Shaw Translation Prize for Ellen Mattson’s Snow. She lives in Kent, England. ALSO BY SVEN LINDQVIST A History of Bombing The Skull Measurer’s Mistake: And Other Portraits of Men and Women Who Spoke Out Against Racism Desert Divers Bench Press The Myth of Wu Tao-tzu Introduction © 2014 by Adam Hochschild “Exterminate All the Brutes” © 1992 by Sven Lindqvist English translation © 1996 by Joan Tate Originally published in Sweden as Utrota varenda jävel by Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1992 Terra Nullius © 2005 by Sven Lindqvist English translation of Terra Nullius © 2007 by Sarah Death Originally published in Sweden as Terra Nullius: En Resa Genom Ingens Land by Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005. Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2014 Distributed by Perseus Distribution CIP data available ISBN 978-1-62097-003-4 (e-book) The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors. www.thenewpress.com Composition by dix! This book was set in Scala Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction by Adam Hochschild “Exterminate All the Brutes” Terra Nullius INTRODUCTION Like many of the most original writers, Sven Lindqvist is hard to pigeonhole. He is not exactly a historian, for his graduate degree is in literature. He is not exactly a travel writer, for he has little interest in the colorful details that make a place seem exotic; he always wants to direct our attention back to our own culture. He is not exactly a journalist, for when he travels to far points on the globe, he is less likely to interview anyone than to tell us about his own dreams. His work does not come in predictable neatly tied packages: he travels through Africa meditating on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness but never reaches the Congo; he goes all the way to Australia to write powerfully about what its native peoples endured but chooses not to interview a single Aborigine. And, for that matter, he’s not someone on whom I, or almost any American writer, can have the last word, for the great majority of his thirty-three books have not been translated from Swedish. If there is an English-language writer whom Lindqvist reminds me of, it might be James Agee: also uncategorizable, also working in many genres, also at times forcing painful detail on his admirers—his masterwork Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is not easy bedtime reading. Yet that book changed and expanded forever our sense of how to see the world, and, at its best, so does the work of Sven Lindqvist. If you asked most Americans or Europeans, for example, to date the great tragic turning points of the modern era, they might say 1914, when World War I began and we saw the toll industrialized slaughter could take, or 1945, when the United States carried this to a new level by dropping two atom bombs on Japanese cities. If you asked Lindqvist, I think he would say 1898 and 1911. Why? These dates, too, have to do with industrialized warfare; the difference is where the victims were. The year 1898 saw the Battle of Omdurman, during which a small force of British and colonial troops, Winston Churchill among them, in a few hours killed more than ten thousand Sudanese and wounded another sixteen thousand, many fatally, most of them falling victim to half a million bullets fired by Hiram Maxim’s latest machine guns. It was the first large-scale demonstration of what this horrific new weapon could do. Thirteen years later, on November 1, 1911, during another long-forgotten war, an Italian lieutenant named Giulio Cavotti leaned out of his open-cockpit airplane and dropped several hand grenades on two oases near Tripoli, Libya. It was the world’s first aerial bombardment. In both cases, of course, the victims Lindqvist draws our attention to were colonial peoples. This, I think, is the insight and the driving passion at the core of the two books in this volume and of several of his others, particularly the remarkable A History of Bombing—where he traces the genealogy of British terror-bombing of German cities in World War II back to similar targeting of civilians in a colonial war in Iraq more than twenty years earlier. To read “Exterminate All the Brutes”, A History of Bombing, or Terra Nullius is to be reminded of how incredibly Eurocentric a view of the world most mainstream historians have. We are accustomed to thinking—in the famous phrase of British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey—of “the lamps . . . going out all over Europe” in 1914 as a catastrophic war began and forget that they were extinguished decades earlier for people on other continents as they experienced European conquest. Almost all of us educated in North America or Europe grew up learning that there were two great totalitarian systems of modern times, each with fantasies of exterminating its enemies: Nazism and Communism. Lindqvist reminds us that there was a third: European colonialism. And, most provocatively, he makes connections between it and one of the others. “Exterminate All the Brutes” takes us deep into the history of Western consciousness in a search for the sources of the very idea of extermination and finds it in many unexpected places. An early “kindergarten for European imperialism,” for example, was the Canary Islands, where some five hundred years ago diseases and weapons brought by conquering Spaniards reduced an estimated eighty thousand indigenous inhabitants to zero in less than a century. How many people who have visited these lovely islands as tourists ever learned this? Not me. Lindqvist also introduces us to Lord Wolseley, eventually commander in chief of the British army at the time of Omdurman, who, in this era when British wars were colonial ones, spoke of “the rapture-giving delight which the attack upon an enemy affords. . . . All other sensations are but as the tinkling of a doorbell in comparison with the throbbing of Big Ben.” Then there is the nineteenth-century birth of scientific racism, which eagerly twisted Darwin’s discoveries to justify the idea that “inferior” races were fated to disappear from the Earth, just like species of plants and animals gone extinct— and implied that there was no sin involved in helping them on their way. And finally, along came plenty of thinkers and politicians who saw this as inevitable. In 1898, the year of Omdurman, one of them declared, “One can roughly divide the nations of the world into the living and the dying.” Who said this? Lord Salisbury, prime minister of Britain. And then comes Lindqvist’s most provocative and unexpected discovery: a German thinker, Friedrich Ratzel, an ardent enthusiast of colonialism, believed that there was a “demonic necessity” for the “superior race” to see to it that “peoples of inferior culture” die out. And who were these inferior people? They included “the stunted hunting people in the African interior” (tens of thousands of whom were wiped out in 1904 in the notorious German genocide of the Herero people of today’s Namibia), Gypsies—and Jews. Hitler had a copy of Ratzel’s book with him in 1924, when he was in prison writing Mein Kampf. “Hitler himself,” writes Lindqvist, “was driven throughout his political career by a fanatical anti-Semitism with roots in a tradition of over a thousand years, which had often led to killing and even to mass murder of Jews. But the step from mass murder to genocide was not taken until the anti-Semitic tradition met the tradition of genocide arising during Europe’s expansion in America, Australia, Africa, and Asia.” Can we prove this beyond doubt? Not without knowing exactly what was in Hitler’s mind. But I defy anyone to read “Exterminate All the Brutes” and not see the Holocaust in a somewhat different light and the Jews, as Lindqvist suggests, as the Africans of Europe. His bold contention has riled some more traditional scholars, deeply wedded to the idea of the Holocaust’s uniqueness. Unique it certainly was in scale, technology, and speed, but Lindqvist makes us realize that it was but one of an appalling series of attempts—the others almost all outside of Europe—to exterminate an entire people from the face of the Earth. Terra Nullius has also not been without its critics, chief among them white Australians who feel that all this history of the shameful treatment of Aboriginal peoples is familiar news by now. To some extent that’s true, but unfortunately, as Lindqvist shows us, not true enough. The achievement of this book, while more complex, again includes reminding us of how people in a country we normally consider enlightened thought so much like Nazis. What would we say, for instance, about a German theorist who, a mere half-dozen years before Hitler took power, wrote, “The survival of the Jews will only cause trouble”? We’d say that this person paved the way to Auschwitz. In Terra Nullius, Lindqvist introduces us to George H.L.F. Pitt-Rivers, a British anthropologist, who wrote in 1927 of Australia, “The survival of the natives will only cause trouble.” By contrast, Pitt-Rivers added, “there is no native problem in Tasmania . . . for the very good reason that the Tasmanians are no longer alive to create a problem.” Hauntingly, Lindqvist quotes an earlier report from similarly minded researchers who described the typical Aborigine as “a naked, hirsute savage, with a type of features occasionally pronouncedly Jewish.” In other ways as well, Lindqvist subtly examines how white Britons and Australians have looked at Aborigines, showing us how their perceptions and theories are so often a projection of white fantasies. Because women used the same form of address for a husband’s brother as for him, for example, early anthropologists theorized that the Aborigines practiced group sex, with brothers owning all women in common. Because Aborigines (unlike whites) used no corporal punishment on their children, their child-rearing was judged inexcusably lax, and their children, half-castes in particular, were often seized and taken from them, in order to be reared in state institutions in ways less “primitive.” Above all, whites eagerly promoted the reassuring illusion that because so much of central and western Australia looked like desert, it couldn’t possibly belong to anyone and so was terra nullius—no one’s land. “There was little appetite for admitting that . . . every stone, every bush, and every water hole had its specific owner and custodian, its sacred history and religious significance.” It was far more convenient to believe that the land was no one’s, which meant it could be used for everything from open-pit mining to testing long-range missiles and British atomic bombs. Lindqvist’s work leaves you changed. “Exterminate All the Brutes” first made me fully aware of one of the real-life models for Joseph Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz and, for a book I was then writing, set me looking for more. Two books later, I found myself writing about the Battle of Omdurman. And no one who reads A History of Bombing will ever again feel that the Allies of World War II fought the “Good War.” Lindqvist opens a world to us, a world with its comforting myths stripped away. You read him at your own risk. —Adam Hochschild

Description: