The Crouching Beast: A United States Army Lieutenant’s Account of the Battle for Hamburger Hill, May 1969 PDF

Preview The Crouching Beast: A United States Army Lieutenant’s Account of the Battle for Hamburger Hill, May 1969

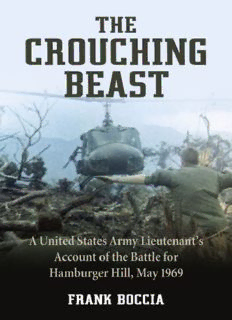

The Crouching Beast A United States Army Lieutenant’s Account of the Battle for Hamburger Hill, May 1969 Frank Boccia McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1308-6 © 2013 Frank Boccia. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover photograph: WO Searcey, Genna’s seatmate, guiding in a Ghost Rider bringing in the first of the Alpha Company troops, at 1300 hours, April 26, 1969. Genna was badly wounded, and Searcey killed, during the NVA attack that night (photograph by Pat Lynch) McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Acknowledgments Preface Author’s Note 1. The Mountains of Viet Nam 2. Firebase Helen 3. The First Patrol 4. Mud Is the Universal Constant 5. The Poor Guys in Korea 6. The Tiger Dines 7. Black Jack 8. Firebase Barbara 9. Firebase Brick 10. Firebase Rakkasan: Abbot’s Tale 11. March Madness 12. Dickson’s Shining Moment 13. Father Haney’s Lament 14. Dennis Helms, Bravo One Six Romeo 15. The Banana Tree 16. The Rao Trang 17. Zeus Frowns 18. The Crater 19. Death Dance of the Ghost Riders 20. Welcome to the 6th NVA Regimental HQ 21. The Body Bags 22. Rescued by the Gnome 23. Black Jack’s Seminar 24. Firebase Airborne 25. Sergeant Samuel Wright RA 26. Palace Guard 27. The Broken Strap 28. The Ordeal of Bravo Four Six 29. The Clearing 30. The Book of Myles Westman 31. Feeling Our Way 32. Sanguis Agni 33. Logan’s Run 34. The Bamboo Corridor 35. Charlie’s Ridge 36. Fratricide 37. The Number Seventeen 38. The Stain 39. The Storm 40. The Naked Beast Epilogue Glossary List of Names and Terms Acknowledgments The list of people who have helped with this manuscript is long. The most obvious ones are those who have taken the time to provide accounts of their actions and perceptions during the six months covered in the book: My brother officers Jerry Wolosenko and Charles Denholm; Joel Trautman and Dan Bresnahan, who not only gave testimony to what occurred with Alpha Company but was invaluable in helping me with the discrepancies and omissions of the after-action report. Gerald “Bob” Harkins, now president of the Hamburger Hill chapter of the Rakkasans, and Mike Smith have been extremely helpful and supporting. Luther “Lee” Sanders, then CO of Delta, and of course, General Honeycutt, who has made me aware of many events that took place out of my ken during the battle. I am grateful to Tom Lough, then CO of the 326th Engineers, and several of the pilots of the Ghost Rider squadron who inserted us into Hill 1485, for their insights and information: Chris Genna, Gene Franck, Luis Molinar, Pat Lynch; all these people helped enormously. And, of course, the men of First Platoon, who have provided both inspiration and information throughout the years. I am grateful to them all, but I must single out Dennis and Beverley Helms, and John and Linda Snyder, for their unrelenting and steadfast support, encouragement and care over the decades. They are four special people. Preface The battle of Dong Ap took place over 11 days, from the 10th to the 20th of May 1969. From a military historian’s perspective, compared to the great battles of the American Civil War and the two world wars, the battle was modest in its scope. Initially, it involved five infantry battalions totaling over 2,000 men, as well as airmen, support artillery, engineers and medical corps personnel from other commands. Fewer than 100 Americans died, among some 500 or so casualties; a minuscule number, compared to the Somme, when 20,000 British soldiers died in less than half an hour, or Cold Harbor, or Saipan. And yet it caused a firestorm of criticism, and earned its sobriquet Hamburger Hill. For those of us who were there, the number of casualties was irrelevant. What mattered was that they were ours, Rakkasans primarily. What mattered to me was that so many of them were mine; men of First Platoon, Bravo Company, 3rd of the 187th. They and many others left their blood on the mountain called by the locals Dong Ap Bia—the Mountain of the Crouching Beast. Casualties were staggering. Alpha Company, the lightest hit of the four companies of the battalion, took over 30 percent casualties; Bravo, just over 50 percent. Charlie lost 60 percent, after replacements—their original roster suffered over 75 percent—and Delta a mind-numbing 75 percent including replacements. When the battalion CP dead and wounded were added, the total represented 60 percent of the entire unit. This is stunning. The two wars in which unit casualties had been the highest, the American Civil War and the First World War, had rarely seen units suffer as much as 50 percent dead and wounded. At the battle of the Somme, which by all accounts represents the nadir in military tactics and is the bloodiest, most sickening example of carnage and destruction the modern world has ever seen on a battlefield, a unit that took 50 percent casualties was classified as destroyed. Such a unit would normally be disbanded. Three of the four company commanders were wounded, two seriously. Of the 14 original platoon leaders, only four made it through the battle, and two of them were lightly wounded; three of the five replacement platoon leaders were also wounded or killed. Three of the four FOs—forward observers—went down; the battalion CO, Lt Col Honeycutt, was wounded twice. NCOs, senior and junior, were also disproportionate casualties: Bravo Company alone lost a first sergeant, were also disproportionate casualties: Bravo Company alone lost a first sergeant, two platoon sergeants and nine squad leaders. The enemy suffered even greater loss. Some 600 dead were buried on the hill itself, in mass graves bulldozed into the flanks of the mountain, but the testimony of the Montagnard tribe that formed the support battalion for the NVA 29th Regiment, who took the brunt of the action, indicates that more than 1,000 died and hundreds more were wounded. The politicians, predictably, were not long in making their opinions known. Ted Kennedy, then still a new and junior senator, denounced the action on the floor; scathing editorials were written, in which the stupidity of the generals was excoriated, particularly so when it was announced, a few weeks later, that we were abandoning the hill we had purchased so dearly. But no war in our history has been as badly reported and as thoroughly misunderstood as the war in Viet Nam, and this is but an example of that. The fact is that we never set out to capture Hill 937; it wasn’t even mentioned in our briefings before the operation. Contrary to published reports, it does not dominate the A Shau valley; there are too many intervening ridges and hills, and the valley floor can’t be seen from its summit. Even on the second day, the 11th, when I was told to move my platoon up the southwestern flank of the hill, it was with the purpose of establishing a battalion CP on top. We had no interest in the hill as a topographical feature, and the only other thing we heard initially was a vague and unsubstantiated reference to a possible NVA supply complex there. No, we didn’t care about the hill. We were there to seek out, find, engage and kill the enemy—the North Vietnamese Army. We didn’t expect them to hold and fight; they seldom did, in the face of as many troops as we had. And when they did hold, and not disappear over the Laotian border, only two kilometers distant, we moved in on them and mauled them until they broke. There was a reason they held their ground. Dong Ap Bia was one of the most heavily fortified hills in all of Viet Nam. It was a perfect defensive position; the ridges leading to its summit were long, narrow and steep-sided, making maneuvering impossible. Laos, as mentioned, was only a couple of kilometers distant, and across its borders were replacements, resupply, medical facilities and a safe avenue of retreat. Other supply areas were within a few kilometers, and so were other regiments, poised to strike our firebases and flanks—as they did on Firebase Airborne, the evening of the 12th. did on Firebase Airborne, the evening of the 12th. The ridge Bravo Company followed, the central of the three western approaches to the hilltop, led eventually to a small clearing; it was a true razorback ridge, no more than a meter or so wide as it approached the crest, and the flanks were not only deep and steep, but choked with dense triple-canopy vegetation. Movement along those ridge flanks was impossible. So in order to reach the top, we had to go through the clearing, about 20 meters wide and perhaps 30 deep, dominated by two small knolls at its eastern end, and by the mountain summit and other, higher ridges on either side. It was full of bunkers, spider holes and automatic weapons positions, and guarded by claymores, shape charges, trip wired grenades and direct RPG fire. I have never seen or heard or read of a more perfect—and deadly—defensive position. So a good part of this book deals with what we went through to breach that clearing, over the 11 days in May. But I begin it much earlier than that, months before May; in mid–December, and it starts not in the A Shau but on a firebase many kilometers to the east called Helen, high on a ridge overlooking the imperial capital of Hue and, not coincidentally, a sprawling base camp called Evans, the home of the Third Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division. It is not that anything of historical significance took place during those intervening months; there were no major battles, and for my platoon, at any rate, no meaningful contact until late April, on Dong Ngai. And when I do begin to recount the battle, my perspective is, by necessity, narrowly focused. The story as I wrote it is not a history, although I emphasize that it is accurate; I have had access to, along with my memory (excellent in my youth), my diary, kept on almost a daily basis; my notebook used while in the field; my letters home; after- action reports; oral and written accounts from other participants, and the research of others who wrote about the battle. But in the main, what I write about is what I saw and experienced directly. It is not a history, but a drama; real, about real events and real people, but a drama. Its protagonists are for the most part the men of First Platoon; I write about them because I know of no other group of men whose story deserves to be told more than theirs. I try to present them as they are; neither cartoon heroes nor unthinking automatons, but human beings of almost incredible resource, resiliency and resolve. They are your neighbors and employees, sons and husbands, students and teachers. And they did extraordinary things. What they

Description: