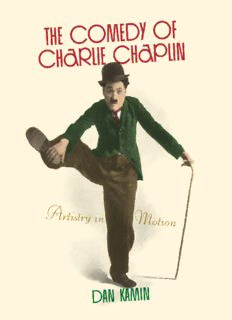

The Comedy of Charlie Chaplin: Artistry in Motion PDF

Preview The Comedy of Charlie Chaplin: Artistry in Motion

The Comedy of Charlie Chaplin Artistry in Motion Dan Kamin THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2008 by Dan Kamin First paperback edition 2011 All images from Chaplin films made from 1918 onwards, copyright © Roy Export Company Establishment. Charles Chaplin and the Little Tramp are trademarks and/or service marks of Bubbles, Inc., S.A. and/or Roy Export Company Establishment, used with permission. Quotations from My Autobiography and My Life in Pictures, copyright © Pac Holding SA. All rights reserved. Used with permission. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available The hardback edition of this book was catalogued by the Library of Congress as follows: Kamin, Dan, 1946– The comedy of Charlie Chaplin : artistry in motion / Dan Kamin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Chaplin, Charlie, 1889–1977—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PN2287.C5K35 2008 791.4302’8092—dc22 2008018036 ISBN: 978-0-8108-7780-1 (paper : alk paper) ISBN: 978-0-8108-7781-8 (electronic) ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Manufactured in the United States of America. For the women in my life, Carol and Hester. Without you, even Charlie Chaplin couldn’t cheer me up. Contents Contents Foreword Acknowledgments A Note to the Reader Introduction: The Surprising Art of Charlie Chaplin Part One Chapter 1: On the Boards Chapter 2: Fooling for the Flickers Chapter 3: Shoot the Mime Chapter 4: Drunk Again Part Two Chapter 5: Gagman Chapter 6: Cast of Characters Chapter 7: Shall We Dance? Part Three Chapter 8: Facing Sound Chapter 9: Swan Song with Music: City Lights Chapter 10: The Machine Age: Modern Times Chapter 11: Split Personality: The Great Dictator Chapter 12: Return Engagement Chapter 13: Monster Movie: Monsieur Verdoux Chapter 14: Full Circle: Limelight Chapter 15: The Banished Monarch Postscript: Teaching Charlie Chaplin How to Walk Select Annotated Bibliography About the Author Foreword People who know of my passion for all things Chaplin occasionally ask me why I’ve never written a book about him. The truth is that I only write books I’d like to read, which presupposes that nobody else has stepped up and done a proper job. But in the vast literature devoted to Charlie Chaplin, there are several books that present a three-dimensional portrait of the man and his art that answer the bulk of the questions I’ve had. I’m thinking of such books as David Robinson’s massive and surely definitive authorized biography, along with such smaller, shining gems as Theodore Huff’s Charlie Chaplin, Lillian Ross’s Moments with Chaplin, and even A. J. Marriot’s surly but invaluable Chaplin Stage by Stage. And there is Dan Kamin’s The Comedy of Charlie Chaplin: Artistry in Motion, an expanded and rethought version of Kamin’s Charlie Chaplin’s One-Man Show, in which the author had the brilliant idea of examining Chaplin through the only communicative tool an actor in silent movies had: movement, command of his body. Of course, thirty seconds of Chaplin shows up the vast majority of silent comedians as comparatively unimaginative processors of gags. Most comedians rise or fall on the quality of their jokes, but great comedians have a special relationship to their material—their specific attitude makes each joke feel customized . . . or should. “Your money or your life,” said to Jack Benny causes a roar; addressed to anybody else, it’s meaningless. Chaplin’s gags have resonance not because they’re always brilliant—although I treasure the sequence with the wood stuck in the grate that he deleted from City Lights, and the feeding machine sequence from Modern Times—but because of his attitude toward them, the dance he does around them, or the preparation that precedes them. The dance of the bread rolls in The Gold Rush is exquisitely done, but what makes the scene hover in your mind for decades is the sequence’s emotional impact, which is only possible because of the time Chaplin has devoted to preparation—the tramp’s isolation in Alaska; the party to which nobody comes; the moment in the spotlight that exists only in his dream. There were comedians who used more of film’s vast potential than Chaplin (yes, Keaton), and there were comedians who got more laughs (Laurel and Hardy, but they got more laughs than anybody), but I’ve yet to see an actor of greater virtuosity than Chaplin, or, for that matter, a filmmaker whose technique was more effectively calculated to present his ideas. The particular glory of an artist is that they change as you do. The artist may be long dead, the work itself frozen in amber, but you see more—or, unfortunately, sometimes less—in it as you age and make return visits. Dan Kamin’s insights are fascinating and invariably apt: A simple declarative sentence like “It is interesting to note that as Chaplin’s sex life became the subject of tabloid headlines, his screen character became less sexually aggressive,” would be belabored by most writers into a chapter, if not an entire book, but Kamin tosses it off in a footnote. Kamin has returned to the films again and again, and this new edition is proof of his even more expansively detailed view of the man who remains, even today, nearly a hundred years after he first tentatively walked onto the Keystone lot in Edendale, the cinema’s premier artist. Scott Eyman is the author of many books on filmmakers, including Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille and Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. Acknowledgments This book is only the latest of my attempts to get Charlie Chaplin out of my system. There are a number of people who must share the blame for my failure. Frank Scheide and Hooman Mehran, coeditors of The Chaplin Revue book series, have repeatedly ensnared me into participating in their dubious literary enterprises. I do so only out of pity, since these unfortunates suffer from an even more virulent form of the disease than I do. Then there are the people I think of as the Chaplin mafia, including Bonnie McCourt, Lisa Stein, Bruce Lawton, Alice Artzt, Shunichi Ohkubo, Ono Hiroyuki, David Totheroh, and Louise Burton, to name a few, all of whom have enabled me through their misguided acts of kindness. Speaking of enablers, Kate Guyonvarch of Association Chaplin in Paris has been all too willing to offer her time and resources, knowing full well what the result would be. She, Josephine Chaplin, and the association allowed me— indeed, encouraged me—to print many of the pictures in this book, no doubt hoping to lure new victims. Cecilia Cenciarelli of Progetto Chaplin has cheerfully provided materials from the Chaplin Archive, housed at the Cineteca Bologna—and why not? The very existence of these organizations attests to the global nature of the crisis. Two generations of Scarecrow Press editors, including most recently Jessica McCleary and Stephen Ryan, must share a portion of the blame as well, though theirs was a hopeless task. Had it been possible to edit Chaplin out of my life, Carol Fryday would surely have done it by now. That our marriage has survived not only Chaplin, but her careful editorial scrutiny of this manuscript, is, like a Chaplin film, a miracle of love and laughter. A Note to the Reader This was supposed to be a revised edition of a book called Charlie Chaplin’s One-Man Show, but it soon became apparent that the book, like almost everything Charlie Chaplin touches in his films, was turning into something else in front of my eyes. It was becoming a new book—based on the old one, to be sure, but so different that it needed a new title. When I wrote the original in the early 1980s, I was cranking 8mm and 16mm prints through small film editors and projecting them onto my living room wall, or taking notes in darkened movie theatres. While there was a certain pioneering charm about having to study the films this way, it wasn’t easy to do. With Chaplin’s complete output now available on DVD I’ve been able to examine the films much more closely. In the process I’ve discovered many gems—gags, scenes, and sometimes whole films—that I overlooked or gave short shrift the first time. I’ve also been able to draw on a wealth of new material that has come out over the past two decades. So many books on Chaplin have been published that there are now books about the books on Chaplin. Significant primary source material, such as the Chaplin studio records and many of his outtakes, has also come to light, so that there is more information available than ever before about the man and his art. But the main reason my old book ended up morphing into this new one is that my ideas have evolved considerably, due in no small part to the doors that opened to me after that first one came out. I was invited to give many presentations on Chaplin at film festivals and colleges, and became involved with a number of intriguing theatrical projects, including plays about Chaplin at Harvard’s American Repertory Theatre and Canada’s Shaw Festival. Symphony orchestras began asking me to create live “silent movies” on stage. Hollywood beckoned as well: I devised the physical comedy sequences for Benny and Joon with Johnny Depp, and helped to re-create Chaplin’s art for the movie Chaplin. Obviously, there could be no better way of putting my ideas about Chaplin to the test than training Robert Downey Jr. for the title role in Chaplin, and I’ve

Description: