The Cloud-Capped Star (Meghe Dhaka Tara) PDF

Preview The Cloud-Capped Star (Meghe Dhaka Tara)

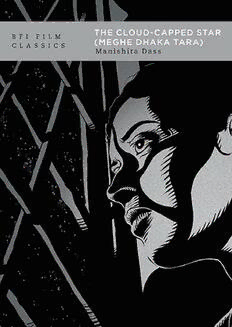

THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR vii Acknowledgments I would like to thank Daniela Berghahn and John Hill for encouraging me to write this book; Rebecca Barden at the BFI, for commissioning it and attentively steering it to publication; Sophia Contento for preparing the visual material for it; and Maitreesh Ghatak for going beyond the call of family duty in helping me weather the emotional cloudbursts that – not surprisingly, given the personal resonances of the book’s subject – accompanied the process of writing it. The book draws on archival research supported by a British Academy Research Grant, and on material from two of my essays: ‘Unsettling Images: Cinematic Theatricality in Ritwik Ghatak’s Films’ (Screen 58:1, Spring 2017) and ‘The Cloud-Capped Star: Ritwik Ghatak on the Horizon of Global Art Cinema’ (in Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories, ed. Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover, Oxford University Press, 2010). viii BFI FILM CLASSICS Prefatory Note/Synopsis Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star, Ritwik Ghatak, 1960, Bengali) has been hailed as ‘a modern masterpiece’ and ‘one of the great classics of world cinema’ (BFI), ‘an extraordinary, revelatory work’ (Adrian Martin) and ‘one of the five or six greatest melodramas in cinema history’ (Serge Daney).1 It is arguably the best-known film by the visionary Bengali film-maker Ritwik Ghatak (1925–76), whose ‘seismographic renderings of trauma’2 have come to haunt world cinema and whose shadow looms large over India’s alternative film culture. The BFI’s decision to release a DVD version in 2002 Neeta in Meghe Dhaka Tara/The Cloud-Capped Star (1960) THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR ix and the recent digital restoration of the film undertaken by Criterion in collaboration with the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project indicate the film’s exalted position in the canon of world cinema. Meghe Dhaka Tara tells the story of Neeta (Supriya Chaudhuri), the eldest daughter of a downwardly mobile middle-class Hindu family from East Bengal, displaced by the Partition of India and struggling to survive in a refugee settlement on the outskirts of Calcutta in the 1950s. Even as a postgraduate student, Neeta largely bears the burden of keeping the family financially afloat. Her older brother Shankar (Anil Chattopadhyaya), who would normally have assumed the responsibility of supporting the family, spends his days practising Indian classical music and dreaming of becoming a great singer, with the encouragement of Neeta, who believes him to be a genius. Their mother (Geeta Dey) is apprehensive about what would happen to the family if and when Neeta leaves home to marry her long-time suitor, Sanat (Niranjan Ray), an ex-student of her father’s and a research scientist. Sanat describes Neeta as ‘a cloud-capped star’ (‘meghe dhaka tara’) in a billet-doux: ‘I didn’t appreciate your worth at first. I thought you were like others. But now I see you in the clouds, perhaps a cloud-capped star veiled by circumstances, your aura dimmed.’ This romantic metaphor acquires a poignant irony as a chain of events not only reveals the shallowness of Sanat’s love for Neeta but also invests this seemingly ordinary young woman with a tragically mythic aura. Through various twists and turns of the plot, Neeta finds herself trapped within her dual role as a provider and a nurturer as her family becomes even more dependent on her earnings. Her father (Bijon Bhattacharya), an eccentric schoolmaster emblematic of a waning Bengali liberal humanism, and her younger brother, Montu (Dwiju Bhawal), a millworker representative of the newly- déclassé Bengali petit bourgeoisie, have debilitating accidents and lose their jobs. Now the family’s sole breadwinner, Neeta abandons her postgraduate studies in order to take up full-time employment and postpones her marriage to Sanat. Unwilling to wait for Neeta, who x BFI FILM CLASSICS cannot bring herself to forsake her family, Sanat ends up marrying her younger sister, Geeta (Geeta Ghatak), with the tacit support and connivance of Neeta’s mother, who sees this as a perfect solution to her dilemma. An indignant Shankar leaves home in protest and Neeta’s doting father watches helplessly while Neeta continues to shoulder her burden in stoic silence. The strains of her life eventually take their toll. When Shankar returns from Bombay after establishing his reputation as a classical singer, he finds Neeta wasting away with tuberculosis, a condition that she has managed to conceal from the rest of the family. He whisks her away to a sanatorium in the hills but it is too late to save her. The film connects Neeta’s individual predicament to the traumatic aftermath of the Partition of India (1947) and a gendered critique of the family through an aesthetic that combines the emotional jolts of melodrama with a neo-realist concern for the everyday and modernist strategies of fragmentation. Note: While the city of Calcutta was officially renamed Kolkata in 2001, I have used ‘Calcutta’ when referring to the city in the pre-2001 period. THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR 1 1 Introduction: Echoes of a Cry Towards the end of Meghe Dhaka Tara, we see the protagonist, Neeta, on the grounds of a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients in the hill station of Shillong, far away from the grimness of her family home in a refugee colony near Calcutta. She sits quietly on a rock as her brother, Shankar, who has come to visit her, tries to distract her with cheerful chit-chat about the family, especially about the mischievous antics of their young nephew, Geeta and Sanat’s son. Suddenly, the usually stoic and reserved Neeta cries out, ‘But I did want to live!’ and breaks down, clinging to her brother, imploring Neeta’s outburst: ‘I want to live!’ 2 BFI FILM CLASSICS him to assure her that she will live: ‘Please tell me that I’ll live, just tell me once that I’ll live! I want to live! I want to live!’ Her desperate yet defiant cry echoes through the landscape, as the camera pans across the surrounding mountains in a dizzying 360-degree turn. Even after her visual image disappears from the screen, Neeta’s disembodied voice reverberates in an empty space – and continues to do so in the Bengali cultural imaginary. A recent Bengali newspaper article claims, in appropriately melodramatic terms, that Neeta’s piercing cry ‘has not only echoed through the hearts of Bengalis as a lament but over the last fifty years, continued to inspire cornered men and women whose hopes have been extinguished’.3 For many viewers familiar with the film’s historical and cultural milieu, including myself, Neeta’s final, uncharacteristic outburst of anguish evokes the thwarted desires and shattered dreams of a generation of displaced Bengalis caught in the crossfire of history. This generation was not a historical abstraction to me as my parents and some of our closest family friends belonged to it. On seeing Meghe Dhaka Tara for the first time in my teens, I was struck by the haunting parallels between Neeta’s story and the lives of two of my favourite aunts: one of my mother’s dearest friends and her older sister. Brilliant, articulate and imaginative students who were encouraged by their liberal middle-class family to pursue higher education, they had to give up on their dreams of becoming a historian and an economist, respectively, in their late teens to Original poster (Artwork: Khaled shoulder family responsibilities Choudhury) THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR 3 in the wake of the Partition and their father’s death. They worked as schoolteachers as they put themselves through college and raised their younger siblings, and then until retirement; never married; and spent their twilight years in a rented apartment, not having managed – despite their frugal lifestyle – to save enough to afford the security of a home of their own. Of course, they did not die young, like Neeta, nor were they crushed by their circumstances. They lived long lives, translating their left-liberal and proto-feminist principles into everyday practice; had a formative impact on the generations of high school students they taught and their surrogate nieces (my sister and I); and never spoke of their disappointments or displayed any hint of bitterness. Nonetheless, their faces get transposed onto Neeta’s every time I watch Meghe Dhaka Tara, and her final scream always reminds me of the broken dreams and lost horizons of hope that my aunts – and countless other women and men – had accepted in silence, with a quiet courage and heart-rending grace akin to Neeta’s habitual response to adversity. Not surprisingly, given its social and emotional resonances and unsettling power, Neeta’s climactic lament is routinely invoked in tributes to the film’s director Ritwik Ghatak and in conversations about his films. It is perhaps fitting that this cry of pain and defiance has become emblematic of the oeuvre of a film-maker who repeatedly described cinema as a means for ‘expressing my anger at the sorrows and sufferings of my people’4 and as a medium that let him ‘shout out’5 and give voice to ‘the screams of protest’6 that had ‘accumulated’ in his psyche as a result of observing the iniquities around him. Ghatak, who came of age in Calcutta in the 1940s, tended to blame the social, political and economic woes of contemporary Bengali society on what he called ‘the great betrayal’: the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in August 1947, which led to the creation of the new sovereign nation-states of India and Pakistan and was accompanied by widespread communal violence, resulting in the deaths of approximately 500,000–1 million people, and one of the largest mass displacements in modern history, involving an estimated 12–15 million people. Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s Urdu poem ‘Subah-e-Azadi’ (‘Dawn of Freedom: 4 BFI FILM CLASSICS Ritwik Ghatak (1925–76) August 1947’) captures the widespread sense of disenchantment, on both sides of the newly drawn border, over the traumatic terms on which independence from British rule had finally been won: These tarnished rays, this night-smudged light – This is not the Dawn for which, ravished with freedom, We had set out in sheer longing… Night weighs us down, it still weighs us down. Friends, come away from this false light. Come, we must search for that promised Dawn.7 The horrors and the tragedy of the Partition – the loss of lives, livelihoods and ancestral homes, and the abrupt sundering of families, communities and emotional bonds – darkened the long-awaited ‘dawn of freedom’ on the Indian subcontinent. Like Faiz and many others of his generation (including my left-liberal parents and their THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR 5 extended family of friends), Ghatak was deeply disturbed by the way in which the Partition seemed to negate or vitiate the promise of the nationalist movement for independence. Until his untimely death in 1976, he continued to agonize over its far-reaching social, cultural and political consequences, especially for the people of Bengal, his home province and one of the regions hardest hit by the Partition. Undivided Bengal, which occupied a total area of 78,389 sq. miles and was perceived in British India as a region where religious differences between the Hindu and Muslim segments of the population were subsumed within a Bengali cultural and linguistic identity, was carved into two separate territorial entities in 1947: Muslim-majority East Bengal, which formed the eastern wing of Pakistan, and West Bengal, which became a state of the federal republic of India. Bengal’s much- vaunted cultural unity lay in tatters, unravelled by sectarian sentiments and Hindu-Muslim riots, and overnight, Bengalis such as Ghatak, who lived in or migrated to West Bengal but had deep roots in East Bengal (or vice versa), saw part of their homeland become a foreign country. While nearly 42 per cent of undivided Bengal’s Hindu population remained in East Pakistan at first, continuing communal tensions led to a steady influx of Hindu refugees, including a large number of middle-class migrants, into West Bengal from 1948 onwards, creating staggering problems of resettlement by the 1950s and exacerbating the socio- economic troubles of an already overcrowded, resource-strapped state. This process continued throughout the 1960s; in 1981, the number of East Bengal refugees in the state was estimated to be 8 million or one- sixth of the population.8 A large number of these refugees settled in or around Calcutta, taking over marshy land in the eastern fringes of the city to build ‘refugee colonies’ – ramshackle settlements similar to the one we see in Meghe Dhaka Tara – and struggled to rebuild their lives from scratch with little or no assistance from the state.9 The government’s failure to create an effective refugee rehabilitation programme not only impinged on the everyday lives of millions of displaced Bengalis but also significantly contributed to West Bengal’s economic decline, political turmoil and social anomie in the post-1947 period.