The Chance Ornament: Aphorisms on Gerhard Richter's Abstractions PDF

Preview The Chance Ornament: Aphorisms on Gerhard Richter's Abstractions

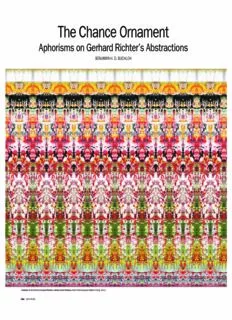

The Chance Ornament Aphorisms on Gerhard Richter’s Abstractions BenjAmin H. D. BuCHlOH Variation IV: 8/16 from Gerhard Richter’s artist’s book Patterns (Heni Publishing and Walther König, 2011). 168 ARTFORum FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 168 1/18/12 6:36 PM The widely acclaimed Tate Modern traveling retrospective “Gerhard Richter: Panorama” arrives at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin on February 12, three days after the venerable German painter celebrates his eightieth birthday. To mark the occasion, art historian Benjamin H. D. Buchloh reflects on abstraction, decoration, and the aleatory in relation to Richter’s latest bodies of work. FeBRuARY 2012 169 FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 169 1/16/12 2:18 PM 1. and bodily space, Richter initiated the aleatory dis- Even the very first of the supposedly first abstract semination and permutational multiplication of paintings Gerhard Richter made in 1966, Ten Colors, color in noncompositional arrangements in 1966, was not a truly abstract painting, since it still copied with 192 Colors, a canvas that effaces any reference a color chart, a swatch similar to those displayed by to the commercial color chart in favor of a mechani- hardware stores and color merchants for commercial cally ordered grid of square color chips. Indeed, the and industrial use. As such, it associated itself with a principles subtending this painting would take on spectrum of color contestations initiated by Marcel increasing importance in the artist’s work, eventually Duchamp in 1918 with Tu m’, a work in which color’s expanding into new registers of noncompositional, supposed capacities to induce psychic and somatic, aleatory, and eventually digitally programmed dis- musical and spiritual forms of experience were dis- tribution, culminating in Richter’s stained-glass win- mantled once and for all—or so it must have seemed dow for the Cologne Cathedral in 2007. In Paris in at the time. 1951, unbeknownst to Richter, Ellsworth Kelly had engaged in similar ventures of noncompositional 2. color arrangements determined by the laws of chance. Color was now declared to be just another industrial The persistence of this new painterly paradigm, readymade, an object like any other item on display from Kelly to Richter, and its emphasis on a paint- in the hardware store, a site that has, since Duchamp, ing’s structural organization according to chance promised an allegorical restitution of use-value in the operations and noncompositionality prove that a face of an emerging totalitarian regime of exchange- historically necessary insight occurred in that period: Gerhard Richter, Zehn Farben (Ten value. Thus, for Richter, the housepainter’s color namely, that the Surrealist aspirations for a psychic Colors), 1966, enamel on canvas, chart (already rediscovered by Jim Dine in his Red automatism of unconscious libidinal liberation could 531⁄4 x 471⁄4". CR: 135-1. Devil Color Charts of 1963) pointed back to that not be credibly secularized or politicized any further lost dimension as much as it distanced itself from all but had to be canceled altogether, since the constitu- the utopian promises that abstract color had seemed tion of the subject and its unconscious formations poised to fulfill in the aftermath of World War I, and could no longer claim to be exempt from any of the with which it had been reinvested with vehemence social systems of linguistic and semiotic control. after World War II, when chromatic consolation was urged on spectators by Rothko et al. 5. Chance as ideology, as the musicologist Konrad Boehmer once described the deployment of these prin- ciples in the work of John Cage, had entered painting in the 1950s in various ways and would soon pose itself as a challenge to Richter as well. A newly liber- ated subject, an author, and an art without any inten- tion appeared on the horizon as one of the great radical promises of the 1960s. Yet the “birth of the reader,” the listener, and the aesthetically unencum- Marcel Duchamp, Tu m’, 1918, oil bered spectator were at best delivered culturally, but on canvas with bottle brush, safety 3. never politically. This dialectic would remain at the pins, and bolt, 271⁄2 x 1193⁄8". The Abstract Expressionists’ aspirations to renew core of Richter’s pictorial anti-aesthetic, perpetually color as psychic and spiritual substance had to be suspended between the involuntary mastery of chance countered by a younger generation of artists in operations and the volatile materiality of paint. America (Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns) and in Europe (Lucio Fontana, Richard 6. Hamilton, Yves Klein) who manifestly situated One of the most bewildering aspects of Richter’s chroma in its seemingly inextricable dependence on work from 1966 onward has been precisely the those regimes that had claimed it for advertising, apparent incompatibility between the indifferently design, and product propaganda. This industrializa- chosen photographs that had formed the iconic core tion of color in painting since the 1950s acknowledged of his oeuvre until that moment, and the painterly Richter’s pictorial anti-aesthetic that consumer culture would now suture every impulse abstraction that would now emerge and henceforth remains perpetually suspended for a psychic space, and every desire for a somatic continuously increase in importance. The question correlative in the material world, to a commodity. posed over and over again (and which has basically between the involuntary mastery of remained unanswered) was how these photographic chance operations and the volatile 4. images could be related to the emerging works of materiality of paint. Advancing this demythification of color as psychic abstraction. After all, our traditional historical nar- 170 ARTFORUM FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 170 1/18/12 6:37 PM ratives had constructed the relations of the two painterly modes either in sequence and in displace- ment (i.e., “This will kill that”) or in a model of returns (i.e., the various rappels à l’ordre, which is to say, the various returns to figuration, as in Picabia and late Pollock). But a model of simultaneity, in which both modes would occur as totally exchange- able equivalents in the oeuvre of an artist, remained for the most part unthinkable and unthought. 7. One way of approaching this question of incompat- ibility might be to recognize that Richter’s deploy- ment of photographs from 1962 to 1965 followed the principles of a universal equalization if not a devalorization of images (in spite of the iconographic subtexts admitted only much later by the artist and formulated even later by his critics). This anti-iconic iconography resulted at least partially from Richter’s enthusiastic encounter with Fluxus in Düsseldorf in 1963, the extent of its impact on his practice remain- ing underestimated until recently. And if Richter did indeed contemplate the legacies of modernist abstraction from the radical Fluxus perspectives of an aesthetic of chance and an absence of intentional- ity, we would have to probe more carefully the modality of his responses to those legacies: Would it still be sufficient to argue (as I have in the past) that his abstractions partook of a general anti-aesthetic, merely operating as parodic or citational (as in a catalogue or in a sampling of past forms of abstrac- tion)—in short, deploying two of the principal dis- tancing devices with which the anti-aesthetic had supposedly performed its various critical operations? 8. What Richter realized early on was that, if the pho- tographic (i.e., the iconic and indexical image) could function in the manner of a readymade, then the purely indexical painterly mark (and its constitutive elements—gesture, facture, pigment, etc.) had to function in the very same way: as neither a purely manual trace of intention nor a purely material trace of process, the manual pressured by industrial pro- duction, and the industrial trace subverted by the mnemonics of an artisanal hand. Abstract painting would have to confront simul- taneously both its originary and innate painterly sublimatory intentions (e.g., the embodiment of Gerhard Richter, 192 Farben vision and desire in projections of unencumbered (192 Colors), 1966, oil on canvas, space) and its actual condition in the present of hav- 783⁄4 x 59". CR: 136. ing been reduced to a merely manual residue, an operative of critical self-reflexivity under duress. From now on it would have to signal its condition of having been subjected not only to total mechaniza- tion but increasingly and manifestly to new forms of FeBRuARY 2012 171 FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 171 1/16/12 2:18 PM Intense chromatic polarities, at touch, an apparent lack of the tragic dimensions of abstraction’s initial aspirations, which had aimed for painterly performance as a substitutional act of com- any type of transcendental experience in 1912, could times saccharine, at times seductive, pensation for absences and loss, effaced or effected now at best be formulated as an affirmative appara- at times histrionic, only intensify by a simulated, offhanded emulation of the very tus of more or less overdetermined geometric design the sense of the deeply anti-aesthetic mechanisms of mass-cultural desublimation that forms. Typically, Stella’s abstractions of the ’70s are skepticism with which Richter painting supposedly resists. no longer noncompositional, in spite of the artist’s initial polemics against relational painting, and their endows his new work. 10. sole purpose seems to have become the tautological Robert Ryman, to the contrary, has counted among affirmation of pictorial planarity and compositional Richter’s favorite painters since the late 1960s, and distribution. Further reflection on the differences this cathexis is as surprising in many ways as Richter’s between Richter’s and Stella’s paintings reveals quite need to distance himself from Johns. After all, a bit more about the precarious conditions of Ryman’s painterly empirio-criticism, the apex of a abstraction in the period of transition from gesture spectacularization. What Walter Benjamin had said late-modernist painterly aesthetic, motivates at best to spectacle, from critical modernist self-reflexivity about the letter—namely, that it had been erected only one half of Richter’s own project. While his is to a seemingly inescapable terminus in which all of into the verticality of the advertising facade at the driven by a similar demand for self-reflexivity and the structural, chromatic, and gestural forms that beginning of the twentieth century after having slept verifiability with respect to the actual optical and abstract painting can conceive in the present end up for centuries in the bed of the book—would now find structural, formal and chromatic (or achromatic) as corporate decoration. its correspondence in pictorial phenomena. In the information that his paintings supply, Richter’s Thus, if the pictorial dialectics of ornament and wake of the 1950s, the spectacularization of chroma, abstractions—quite unlike Ryman’s—refuse that cir- decoration reappear in Stella’s work for the first time facture, and gesture would take its course, initially cumscription as their ultimate norm and confining in postwar painting, we have to recognize that these with Pollock (and then much more ostentatiously parameter. Instead they seem to suggest incessantly are categories that, despite their claims to trans- with Fontana, Georges Mathieu, and Klein), becom- that painting has to confront more than its proper historical neutrality, are as deeply dependent on his- ing an inextricable condition of abstraction that all parameters of production and perception, and that the torical and social formations as gesture and chro- subsequent painting would have to confront. circumspect vision of painting has to circumscribe and matic choice, as compositional order or chance encompass more than the apex of an artist’s extremely operation. The very fact that painting once again 9. differentiated forms of critical self-reflexivity. acquires the condition of ornament necessitates the Richter harbors a strangely intense predisposition to instant questioning of those surfaces it will adorn differentiate himself from two painters in particu- 11. and those structures it will obscure with its decors. lar—two artists whom one might at first sight have Richter’s almost uncanny anticipation of the social In other words: What is the painter’s active or passive considered to be among his closest allies. They are pressures and ideological demands to which abstrac- participation in the affirmative obscurantism that almost his exact peers agewise, and they emerged as tion would from then on be subjected emerges even decoration has traditionally afforded the orders of painters at the very moment (or slightly earlier than) he more clearly when compared with Frank Stella’s power, deposited in architecture just as much as in did, in the early 1960s: Jasper Johns and Ed Ruscha. painterly production during the late 1960s and ’70s. the surfaces embellishing architecture? A seemingly overt and all too obvious proximity— Gesture, facture, and painterly ductus had been sus- too close for comfort (painting and the readymade, pended early on by Stella in favor of an impeccable 13. painting and the photograph)—would offer itself as anonymity of execution. Their effacement would And even if we have said that the assimilation of one quick yet rather simplistic explanation for signal and seal the disappearance of subjectivity from chromatic choices to the regimes of consumption had Richter’s almost compulsory distantiation; but it is painterly production, and this erasure would lay the become an inescapable condition for New York deeply dissatisfying as an explanation, since simplic- groundwork for Minimalism’s surrender to techno- School artists of the second generation, it should be ity is inadequate to discussion of any of these artists. logical and corporate order. While initially radical in noted that by the late 1960s the deployment of color Therefore, something else must be at stake, and its its negations of painterly intention and agency, this in painting and sculpture had actually become uni- comprehension might clarify other facets of Richter’s erasure of the subject also advanced an entropic posi- versally problematized. Artists of the post-Pop and peculiar distinction within the dialectics of his paint- tion that would cancel out every utopian aspiration post-Minimalist generation had become fully con- erly projects: On the one hand, one aspect that he to arise from an alliance between avant-garde produc- scious of precisely these entrapments of the merely might loathe in Johns is the extreme cunning and tion and critical forms of knowledge. This endorse- decorative potential of geometrically structured care, what one could almost call Johns’s artisanal ment of the subject’s apparently inevitable submersion color. All serious practices from Robert Morris’s to fetishism of painterly execution (e.g., the precious- within the technocratic and corporate organization of Richard Serra’s, from Eva Hesse’s to Bruce Nauman’s, ness of the encaustic), not to mention the hermeti- perception and experience now generated a new vari- initiated new forms of resistance against abstrac- cism of his iconography. None of that has ever ant of the conventional deception that painting could tion’s false redemptions, generating multiple artistic appealed to Richter’s pictorial anti-aesthetic, which recover its autonomy in a return to the decorative (as, maneuvers in an achromatic post-Minimalism. Their might be the reason he has always claimed Roy for example, in Stella’s 1967–69 “Protractor” series). initial articulation foregrounded the molecular Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol as his primary refer- details of painterly or sculptural process, the phe- ences from the American repertoire. Ruscha, on 12. nomenological inscription of the subject within the the other hand—in Richter’s misreading, at least— What Stella’s highly controlled forms of painterly apparently infinite inequalities and irregularities of represents the utter opposite: a certain lightness of containment would teach us first of all was that production and materials, and the potential forms of 172 ARTFORum FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 172 1/16/12 2:18 PM resistance to and subversion of the forms of power inherent in accident and aleatory organization. These strategies were supposedly less easily recuperated by the principles of design and decoration and less easily co-opted to serve the affirmative functions that cul- ture can provide the corporate state. 14. Thus, if we have known since Stella that the struc- tures of painterly containment that mimic techno- logical rationality lend themselves perfectly to ornamentation and decoration, we must pose the question with similar acuity when encountering Richter’s recent large-scale abstract paintings, real- ized with the semi-mechanical device of the squeegee and suspended between an almost trance-inducing chromatic opulence and an intrusively concrete spec- ificity of procedural and processual detail. Fully documented in Corinna Belz’s new docu- mentary, Gerhard Richter Painting (2011), the squeegee process becomes transparent as an opera- tion at the extreme opposite end from what chance operations in the wake of the Surrealist legacies of automatism had still promised: Starting the produc- tion of each canvas with strange rehearsals of various forms of gestural abstraction, as though moving Gerhard Richter, Blumen (Flowers), 1992, oil on canvas, 161⁄8 x 20". through recitals of its legacies, in the final phases CR: 764-2. Richter seems literally to execute the painting with a massive device that rakes paint across an apparently carefully planned and painted surface. Crisscrossing the canvas horizontally and vertically with this rather crude tool, the artist accedes to a radical diminishment of tactile control and manual dexter- ity, suggesting that the erasure of painterly detail is as essential to the work’s production as the inscrip- tion of procedural traces. Thus an uncanny and deeply discomforting dialectic between enunciation and erasure occurs at the very core of the pictorial production process itself, opening up the insight that we might be witnessing a chasm of negation and destruction as much as the emergence of enchanting coloristic and structural vistas. If a critic such as T. J. Clark in his recent, exqui- site essay “Grey Panic” (London Review of Books, November 17, 2011) can wonder whether the size, frequency, and multitude of Richter’s large-scale abstractions risks pushing them into the realm of corporate decor, we have been given notice and rea- son to look perhaps more carefully at the actual structure of these abstractions, probing whether the methods by which they were produced might offer evidence of an innate or constructed resistance against that fate. Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes After all, there is no longer any guarantee that Bild (Abstract Painting), 1977, what had started with the emphasis on removing the oil on canvas, 885⁄8 x 783⁄4". CR: 417. hand from the pictorial process in order to have FeBRuARY 2012 173 FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 173 1/16/12 2:18 PM opposition to the extreme rigor of the second major group of Richter’s new work in abstraction, the large-scale digital prints with which the glass pieces were combined when first exhibited in Paris last year. In the four series of glass paintings—the first hav- ing been called “Sinbad,” 2008, followed by the equally Orientalizing titles “Perizade,” “Ifrit,” and “Abdallah” for the subsequent series (all 2010)— Richter seems merely to arrest (rather than to paint) the arbitrary flows of highly liquefied enamel in various, apparently random morphologies and chro- matic constellations on rectangular glass sheets. Paint now appears as an emulsion, as though in a technical test or in the manner of a chemical sample applied to a surface. Or it functions like a gel, oscil- lating between the potential transparency and the actual opacity of chromatic figure and support struc- ture. (The enamel is ultimately sandwiched between the glass and a Dibond support.) Sitting like a chemi- cal film on a surface that refuses to absorb and anchor the wet paint, these puddles shift aimlessly—until they dry, of course—the more or less aleatory consequence of their relative liquidity or elasticity. Above: Gerhard Richter, Ifrit, 2010, Below: Gerhard Richter, Perizade, 16. enamel behind glass mounted on 2010, enamel behind glass Dibond, 135⁄8 x 181⁄8". CR: 915-22. mounted on Dibond, 223⁄8 x 16". Obviously, this deceptively crude denial of all expres- CR: 916-8. sive or iconic potentials of seemingly randomly applied paint and pigment shows color in its purest industrial state, so to speak. Operating in tandem with their abject morphologies, these intense chro- matic polarities, at times saccharine, at times seduc- tive, at times histrionic, only intensify the sense of the deeply anti-aesthetic skepticism with which Richter endows his new work. When trying to describe the glass paintings’ non- gestural agitation, one might be tempted at first to say that their structures are meandering or undulat- ing, yet neither of these terms adequately describes painting compete with the industrial readymade the works’ distinctly nonornamental patterns, since would not inevitably lead to the technocratically they are clearly voided of any intentionality, most ordered assimilation of the body to the rules of a certainly of the serial repetition that constitutes the spectacularized technological universe or to paint- traditional definition of the ornament. ing’s wholesale fusion with the abstracted rationality of the global digital economy. 17. By contrast, in the second and dialectically opposite 15. new series of digital prints, titled “Strips,” 2011, Confronting two groups of Richter’s very recent Richter’s “facture” now has been totally subsumed works, from 2010 and 2011, we must pose these within the registers of a highly developed technological questions all the more succinctly. The first of these application of digital printing of rigorously parallel, groupings comprises four rather strange series of extremely refined and reduced chromatic striations. violently chromatic objects—and they must be con- These “Strip” “paintings” emerged from a para- sidered objects rather than paintings, since they were doxical process in which the artist subjected one of realized by pouring paint onto glass panes. These his earlier large-scale abstractions (Abstract works seem to consist of nothing but the perfor- Painting, 1990 [CR: 724-4]) to a series of program- mance of the pure painterly process, delivered almost matically anti-painterly operations—exceeding the as a calamitous antidote and in manifest dialectical violence of the squeegee’s operations on abstraction 174 ARTFORUM FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 174 1/18/12 6:37 PM In his new work, Richter by far—in order to produce a detailed and volumi- sequence), were deployed to generate visual and tex- nous documentation of the digital breakdown of tual processes of quantitative and qualitative orga- produces a detailed and abstraction for the pages of a book, the massive vol- nization, contesting those compositional operations voluminous documentation ume Patterns (published by Walther König in that had hitherto remained within the mythical of the digital breakdown Cologne and Heni Publishing in London in 2011). privilege of artistic intentionality. of abstraction. At first it appears as though one of Richter’s by Yet after further inspection, it turns out that the now “classic” gestural abstractions was merely sub- operative principles of Patterns are actually more jected to a deceivingly simple series of mathematical complex than merely one mathematical progression. partitions and multiplications, a progression not An additional dimension results from a second oper- uncommon to painterly and sculptural operations ation being performed after the procedures of divi- since Judd’s and LeWitt’s Minimalism. These proce- sion, namely that of doubling. Each of the pictorial dures of temporal and spatial quantification, radical- fragments resulting from the initial divisionary cuts ized in the work of Hanne Darboven and Mario is now matched with its inverted double, generating Merz (one thinks of his focus on the Fibonacci increasingly intensifying, even dizzying prolifera- Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting), 1990, oil on canvas, 361⁄4 x 491⁄2". CR: 724-4. FeBRuARY 2012 175 FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 175 1/16/12 2:19 PM Variation I: 2/2 from Gerhard Richter’s artist’s book Patterns (Heni Publishing and Walther König, 2011). 176 ARTFORum FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 176 1/16/12 2:19 PM FeBRuARY 2012 177 FEB.feat.Buchloh.Richter.indd 177 1/16/12 2:19 PM

Description: