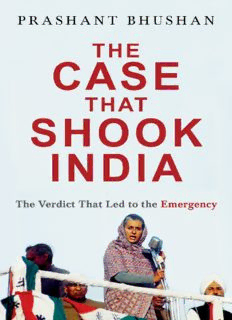

The Case That Shook India: The Verdict That Led to the Emergency PDF

Preview The Case That Shook India: The Verdict That Led to the Emergency

PRASHANT BHUSHAN THE CASE THAT SHOOK INDIA The Verdict That Led to the Emergency Foreword by M. Hidayatullah PENGUIN BOOKS Contents Foreword Preface to the New Edition Introduction 1 PRELIMINARY COURT PROCEEDINGS 1. From Electoral Battle to Court Battle 2. The Petition 3. The PM in Court 2 IN THE HIGH COURT 4. The Petitioner’s Opening Arguments 5. The Attorney-General Defends the Amendment 6. The PM’s Counsel 7. The Petitioner’s Rejoinder 8. The Verdict 3 THE REPERCUSSIONS 9. Rumblings after the Judgment 10. The Stay Order 11. Law? What Law? 4 VALIDITY OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT 12. ‘It Destroys Democracy’ 13. ‘PM Can Be above the Law’ 14. ‘Amendment Is Like a Firman’ 15. Emergency Measure or Tranquillizer? 5 VALIDITY OF THE ELECTION LAW AMENDMENTS 16. Rules of the Game Changed Retrospectively 17. ‘Rules Not Changed, Merely Clarified’ 18. ‘Parliament Cannot Interpret the Law’ 19. The Supreme Court Judgment 20. Epilogue: From Court Battle to Electoral Battle APPENDICES 1. Testimony of Yashpal Kapoor 2. Testimony of Mrs Indira Gandhi 3. The Supreme Court Reviews the Kesavananda Bharati Case 4. Review Application against Justice Beg’s Judgment 5. The Representation of People Act, 1951—Part VII, Section 123 6. The Representation of People (Amendment) Act, 1974—No. 58 of 1974 7. The Election Laws (Amendment) Act, 1975—No. 40 of 1975 8. The Constitution (Thirty-ninth) Amendment Act, 1975 Footnotes 2. The Petition 3. The PM in Court 4. The Petitioner’s Opening Arguments 5. The Attorney-General Defends the Amendment 6. The PM’s Counsel 9. Rumblings after the Judgment 11. Law? What Law? 12. ‘It Destroys Democracy’ 13. ‘PM Can Be above the Law’ 14. ‘Amendment Is Like a Firman’ 15. Emergency Measure or Tranquillizer? 16. Rules of the Game Changed Retrospectively 19. The Supreme Court Judgment 1. Testimony of Yashpal Kapoor 3. The Supreme Court Reviews the Kesavananda Bharati Case Acknowledgements Follow Penguin Copyright Foreword Elections to Parliament and the legislatures of the states are regulated in two ways by law. The first relates to the conduct of the elections by the Election Commission and the second to the personal conduct in it of the candidates. Unlike in other countries, the duty of deciding whether the election was fair and free and if the candidate was guilty of a corrupt practice is entrusted to the High Court and finally to the Supreme Court. After the election is over, the defeated candidate or a voter can challenge the election of the successful candidate by proving irregularities in the conduct of the election by the authorities and/or by proving corrupt conduct on the part of the candidate. In no other way can the result of the poll be challenged. The courts apply to such cases the standards which they usually apply in trials before them. Such cases are like any other case. The allegations made must be strictly proved. Some judges call these quasi-criminal proceedings. This is not an apt description. They rather resemble the trial of allegations of fraud, subject to this that the benefit of the doubt goes to the successful candidate. Ordinarily, I have found more perjury in these cases than in others. Political motivation often colours evidence and courts have to be very careful in assessing partisan testimony. This task becomes even more difficult when the actions of the candidate are also partly referable to his official position. Such was the case dealt with here. The book deals with the election petition filed by Raj Narain to challenge the election of Mrs Gandhi in the 1971 election to Parliament. The author has recorded the day-to-day progress of the case through all stages. He is the son of the counsel for Raj Narain and was presumably present at conferences and in the courts. He has first-hand knowledge of all facts. He has narrated them in a very readable form, describing the proceedings objectively. He has also outlined the many steps by which legislative interference righted what was found wrong at the trial. So much so that the Supreme Court was not even allowed to decide the case in appeal. This was an unusual and undesirable feature of the case. Only one case (McCardie case) was withdrawn from the Supreme Court of the United one case (McCardie case) was withdrawn from the Supreme Court of the United States. It was not an election case but never afterwards was a pending case withdrawn from the courts. All the events are told without acrimony by the author and the comments that one finds are legitimate. I have had my share of election trials as a judge of the High Court and the Supreme Court. Twice I unseated ministers and once upheld an election. There is no doubt that Justice Sinha proved equal to the task. He decided every issue adequately and his reactions during arguments were also relevant and proper. Whether one agrees with his conclusions or not, none can accuse him of taking a strained view of facts. It must be remembered that a person in authority can and should always prevent from acting overzealously the officials who go out of their way to act in aid of such a candidate. The higher the position of the candidate and the more the availability of official aid, the more the risk of allegations. Justice Sinha, in my judgment, has rightly been strict. Although I do not say that I agree with him on every point pro or con, this much I can say, that my approach, by and large, would have been similar. In any event Justice Sinha and Judge Sirica of the Watergate case have much in common just as there is a parallel between Shanti Bhushan and Jaworski in the same case. I have enjoyed reading the book and have found much that was not in the newspapers and I recommend it to the reader. Bombay M. Hidayatullah 1 October 1977 MA (Cantab); LLD, Bencher Lincoln’s Inn and former Chief Justice of India Preface to the New Edition It’s been forty years since The Case That Shook India was published. The book has been out of print now for more than thirty-five years and during these years many people have asked me for copies of this book, including lawyers, law students and academics. I have been giving out photocopies of the book to several people and then many suggested that I should get it republished. I am aware that this book has inspired a number of students to study and practise law and hope that it continues to do so. The Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain1 case was important for several reasons. It was the first time in independent India’s history that a Prime Minister’s election was set aside. It was also the first time that a constitutional amendment was struck down on the basic structure doctrine that had been propounded a couple of years prior, in the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973). It was also the first time that election laws had been retrospectively amended to validate the annulled election of the Prime Minister. The hearing of the case in the Supreme Court of India took place during the Emergency, when fundamental rights had been suspended, press censorship was enforced and therefore there was no public reporting of the case or its hearings. While it was being heard in the Supreme Court, my notes were probably the only ones available as a record of what really transpired during the hearing. I had taken detailed notes of the hearing including the questions asked by the judges and their responses by the counsels, many of which have been reproduced in the book. The case also impacted Indian politics in a big way. The elections that ensued after the Emergency saw the wiping out of the Congress and the installation of the first non-Congress government at the Centre. That government however collapsed within two years, due to infighting amongst the leaders of the various parties who had hastily come together to form the Janata Party. This then led to the split of the Janata Party and the formation of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). This was a landmark development in Indian politics. The BJP contested its first election in 1984, soon after Mrs Gandhi’s assassination, when it won only two seats. By the early 1990s, however, the BJP had stirred up the Ram Janmabhoomi campaign, and riding on its back, it won a substantial number of seats, which paved the way for its eventual victory in 1996.2 The ascendance of the BJP in the twenty-first century has been one of the most significant events of Indian political history. This can be attributed largely to the vacuum left by the Congress. Modi’s rise too can be attributed partly to the anti-corruption movement (Jan Lokpal movement) that took place in the country in the year 2011–12. He used the momentum created by that movement to demolish the Congress with the promise of ending corruption, graft and black money. Arvind Kejriwal also did the same for coming to power in Delhi. Unfortunately, neither of them has appointed a Lokpal yet. In fact, it has been reported that Modi’s government has not worked to strengthen the anti- corruption institutions like the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), Central Vigilance Commission (CVC), the whistle-blower law and even the Prevention of Corruption Act.3 Coming back to the central issue of the Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain case, it is unfortunate that the spectre of dubious electoral funding has not gone away even today, more than forty years after the judgment in the case. Currently the law is that the political parties are allowed to accept cash donations up to 20,000 from each person, which are not required to be reported. Donations above that figure need to be reported to the Election Commission, the details of which can thereafter be obtained by citizens under the Right to Information (RTI) Act 2005. The Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) has been obtaining such details and has recently discovered that about two-thirds of political parties’ funds come from unaccounted sources. Among the national parties, 83 per cent of the total income of the Congress and 65 per cent of the BJP came from unknown sources.4 Since parties are not required to keep any accounts of who has donated the money or how much has been received, they simply report that they received a lump sum amount as cash donations from undisclosed donors. This lump sum amount is usually in the multiples of hundreds of crores of rupees. This has led to parties accepting a lot of black money in large amounts from various donors as illustrated in the Birla–Sahara diaries also. On top of this, there is the problem of political parties not coming within the ambit of the RTI Act, though the

Description: