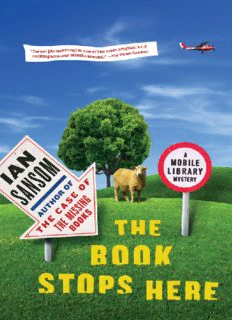

The Book Stops Here aka The Delegates' Choice PDF

Preview The Book Stops Here aka The Delegates' Choice

B O O K THE S T O P S H E R E A MOBILE LIBRARY MYSTERY I A N S A N S O M For the Group Contents 1 ‘I resign,’ said Israel. 1 2 ‘Sorry, Linda,’ he said when they arrived. It was his… 22 3 The meeting had ended, as was traditional at Mobile Library… 36 4 He was packing! Israel Armstrong was packing up and getting… 47 5 They very nearly missed the ferry. 62 6 Israel vomited continually and consistently for most of the journey,… 72 7 Israel’s mother was not a good cook. It was a… 96 8 For a long time he couldn’t get to sleep. First… 123 9 Stolen cars in London are of course ten a penny,… 135 10 Israel was glad that he’d managed to persuade his mother… 156 11 The address they’d been given was just by Wandsworth Bridge. 181 12 Gloria still hadn’t phoned. Or texted. Or indeed turned up,… 200 13 ‘This is madness,’ said Ted. 216 14 When Israel and Ted arrived back at the site the… 243 15 Britain’s premier—and only—convention of mobile librarians, organised by the Chartered… 270 16 The police decided that under the circumstances Israel and Ted… 290 17 They were driving back through England in silence. 302 Acknowledgements About the Author Other Books by Ian Sansom Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher 1 I ‘ resign,’ said Israel. ‘Aye,’ said Ted. ‘I do,’ said Israel. ‘Good,’ said Ted. ‘I’ve made up my mind. I’m resigning,’ said Israel. ‘Today.’ ‘Right you are,’ said Ted. ‘I’ve absolutely had enough.’ ‘Uh-huh.’ ‘Of the whole thing. This place! The—’ ‘People,’ said Ted. ‘Exactly!’ said Israel. ‘The people! Exactly! The people, they drive me—’ ‘Crazy,’ said Ted. ‘Exactly! You took the words right out of my mouth.’ ‘Aye, well, you might’ve mentioned it before,’ said Ted. ‘Well, this is it. I’m up to—’ ‘High dough,’ said Ted. ‘What?’ said Israel. ‘You’re up to high dough with it.’ ‘No,’ said Israel. ‘No. I don’t even know what it means, up to high dough with it. What the hell’s that supposed to mean?’ ‘It’s an expression.’ ‘Ah, right yes. It would be. Anyway, I’m up to . . . here with it.’ ‘Good.’ ‘I’m going to hand in my resignation to Linda.’ ‘Excellent,’ said Ted. ‘Before the meeting today.’ ‘First class,’ said Ted. ‘Before she has a chance to trick me out of it again.’ ‘Away you go then.’ ‘I am so gone already. I am out of here. I tell you, you are not going to see me for dust. I’m moving on.’ ‘Mmm.’ ‘I’m going! Look!’ ‘Ach, well, it’s been a pleasure, sure. We’re all going to miss you.’ ‘Yes,’ said Israel. ‘Good,’ said Ted. ‘So,’ said Israel. ‘You’ve time for a wee cup of coffee at Zelda’s first, mind? For auld time’s sake?’ ‘No!’ said Israel. ‘I need to strike while the—’ ‘And a wee scone, but?’ 2 IAN SANSOM Israel looked at his watch. ‘Meeting’s not till three,’ said Ted. ‘What day is it?’ said Israel. ‘Wednesday.’ ‘What’s the scone on Wednesdays?’ ‘Date and almond,’ said Ted, consulting his mental daily- special scone timetable. Israel huffed. ‘All right,’ he said. ‘But then we need to get there early. I am definitely, definitely resigning.’ They’d had this conversation before, around about mid- week, and once a week, for several months now, Israel Arm- strong BA (Hons) and Ted Carson—the Starsky and Hutch, the Morse and Lewis, the Thomson and Thompson, the Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the Dante and Virgil, the Cagney and Lacey, the Deleuze and Guattari, the Mork and Mindy of the mobile library world. Israel had been living in Tumdrum for long enough—more than six months!—to find the routine not just getting to him, but actually having got to him; the self-same rainy days which slowly and silently became weeks and then months, and which seemed gradually to be slowing, and slowing, and slowing, almost but not quite to a complete and utter stop, so that it felt to Israel as though he’d been stuck in Tumdrum on the mobile library not just for months, but for years, indeed for decades almost. He never should have taken the job here in the first place; it was an act of desperation. He felt trapped; stuck; in complete and utter stasis. He felt incapacitated. He felt like he was in a never-ending episode of 24 or a play by Samuel Beckett. ‘This is like Krapp’s Last Tape,’ he told Ted, once they were settled in Zelda’s and Minnie was bringing them coffee. THE BO O K ST O P S HERE 3 ‘Is it?’ said Ted. ‘Are ye being rude about my coffee?’ said Minnie. ‘No,’ said Israel. ‘I’m just talking about a play.’ ‘Ooh!’ said Minnie. ‘Beckett?’ said Israel. ‘Beckett?’ said Minnie. ‘He was a Portora boy, wasn’t he?’ ‘What?’ said Israel. ‘In Enniskillen there,’ said Minnie. ‘The school, sure. That’s where he went to school, wasn’t it?’ ‘I don’t know,’ said Israel. ‘Samuel Beckett?’ ‘Sure he did,’ said Minnie. ‘What was that play he did?’ ‘Waiting for Godot?’ said Israel. ‘Was it?’ said Minnie. ‘It wasn’t Educating Rita?’ ‘Riverdance,’ said Ted. ‘Most popular Irish show of all time.’ ‘That’s not a play,’ said Israel wearily. ‘Aye, you’re a theatre critic now, are ye?’ ‘Och,’ said Minnie. ‘And who was the other fella?’ ‘What?’ said Israel. ‘That went to school there, at Portora?’ ‘No, you’ve got me,’ said Israel. ‘No idea.’ ‘Ach, sure ye know. The homosexualist.’ ‘You’ve lost me, Minnie, sorry.’ ‘Wrote the plays. “A handbag!” That one.’ ‘Oscar Wilde?’ ‘He’s yer man!’ said Minnie. ‘He was another Portora boy, wasn’t he, Ted?’ Ted was busy emptying the third of his traditional three sachets of sugar into his coffee. ‘Aye.’ ‘Zelda’s nephew went there,’ said Minnie. ‘The one in Fer- managh there.’ ‘Right,’ said Israel. ‘Anyway . . .’ 4 IAN SANSOM