The Bloomsbury Handbook to Edwidge Danticat PDF

Preview The Bloomsbury Handbook to Edwidge Danticat

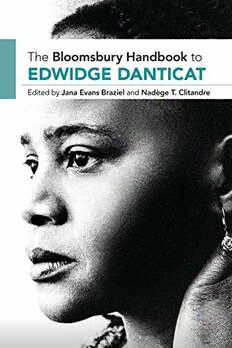

iixx ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Jana and Nadège would like to thank our friends, family, and colleagues for their vital contributions to this collection. Above all, we thank Edwidge Danticat for her input, ideas, creative collaboration, and, of course, for her beautiful words, her passion, her brilliance, and her morally grounded convictions as a writer. For the beautiful photograph of Edwidge and for permission to use it for the cover, we thank photographer Mark Dellas. For reprint permissions, we also thank Maya Solovej, Danticat’s agent; Mary Ellen McNeil, University of Virginia Press; Ginetta Candelario, Smith College and editor of Meridians ; and Diane Grossé, Duke University Press. All of the following are reprinted with their gracious permissions: Clitandre, Nadège T. “Appendix: Interview with Edwidge Danticat.” Included in the monograph, Edwidge Danticat: Th e Haitian Diasporic Imaginary . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2018. Danticat , Edwidge. “ ‘ All Geography Is within Me’: Writing Beginnings, Life, Death, Freedom, and Salt .” World Literature Today , 93 , no. 1 (winter 2019 ): 59–65 . Danticat , Edwidge. “Haiti Faces Diffi cult Questions Ten Years aft er a Devastating Earthquake.” Th e New Yorker (January 11, 2020), https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/haiti- faces-diffi cult-questions-ten-years-aft er-a-devastating-earthquake. Loichot, Valérie. “ Edwidge Danticat’s Kitchen History .” Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism , 5 , no. 1 ( 2004) : 92–116 . 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd iixx 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 33 EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION: A LITERARY LIFE AND LEGACY: DANTICAT’S WRITERLY INHERITANCES Jana Evans Braziel and Nadège T. Clitandre Celebrated writer, passionate activist, literary voice, imaginative wordsmith, and heartfelt conscience of a generation who is an outspoken critic of racism, anti-immigrant politics, police brutality, sexual violence, military interventions, and hemispheric imperialism, Edwidge Danticat is a beloved writer who has an extensive literary oeuvre that moves across multiple genres (short story, novella, novel, memoir, travel narrative, essay, and hybrid, experimental forms). An award-winning author (Neustadt International Prize, Ford Fellowship, Pushcart Prize) and a MacArthur Fellow, Danticat is also an accomplished and well-known author; and her work merits comprehensive and transcontinental engagement. Edwidge Danticat is the most important Haitian-American writer today, and she was a pioneering voice among Haitian diasporic writers writing in English, rather than French or Créole. Born in Port- au-Prince, Haiti, in 1969, Danticat was raised by an aunt in Belair, before migrating to the United States to join her parents in Brooklyn in 1981. She was twelve years old at the time. Like so many other Haitian diasporic writers, Danticat’s works stand in the shadows cast by Duvalierism, the regimes of François Duvalier (from 1957 to 1971) and Jean-Claude Duvalier (from 1971 to 1986), and post-Duvalier militarism and dictatorship in the nation. Danticat studied French literature at Barnard College, where she graduated with a BA in 1990, before studying creative writing at Brown University and earning the MFA degree in 1993. A prolifi c and beloved writer, Danticat’s works of fi ction and nonfi ction include Breath, Eyes, Memory (1994), an Oprah Book Club selection; Krik? Krak! (1996), a National Book Award fi nalist; Th e Farming of Bones (1998); Aft er the Dance (2002); Behind the Mountains (2002); Th e Dew Breaker (2004); Anacaona: Golden Flower, Haiti, 1490 (2005); Brother, I’m Dying (2007); Create Dangerously (2010); Eight Days: A Story of Haiti (2010); Tent Life: Haiti (2011); Claire of the Sea Light (2013); Th e Last Mapou (with Édouard Duval-Carrié) (2013); Mama’s Nightingale: A Story of Immigration and Separation (2015); Untwine: A Novel (2015); Th e Art of Death: Writing the Final Story (2017); My Mommy Medicine (2019); and Everything Inside (2019). Danticat has also edited four collections of short stories, poems, and essays: Th e Butterfl y’s Way: Voices from the Haitian Dyaspora in the United States (2003); Haiti Noir (2010); Best American Essays 2011; and Haiti Noir 2 (2013). Edwidge Danticat is one of the most celebrated and beloved contemporary writers, yet, to date, there exists only one monograph (Clitandre’s E dwidge Danticat: Th e Haitian Diasporic Imaginary (2018)), one edited collection, and one collection of interviews on Danticat even though she is arguably one of the most important writers of the twentieth and twenty- fi rst centuries. Author of more than eighteen books—including six works of fi ction, fi ve works of nonfi ction, seven young adult and children’s books, as well as scores of essays and 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 33 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 4 The Bloomsbury Handbook to Edwidge Danticat articles—Edwidge Danticat is one of the most important contemporary writers: she is also one of the most celebrated and award-winning authors of our era, having won ten literary prizes and awards and having been nominee and fi nalist for many more. Among her distinctions include the high honor of MacArthur Fellow (2009), Ford Foundation Fellow (2017), and the Prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature (2018), and the Vilcek Prize for Literature (2020). Danticat has also edited four volumes of fi ction and penned numerous prefaces and introductions to other books. Books addressing Danticat’s literary and historical importance include Martin Munro’s E dwidge Danticat: A Reader’s Guide (2010), Nadège T. Clitandre’s Edwidge Danticat: Th e Haitian Diasporic Imaginary (2018), Maxine Lavon Montgomery’s Conversations with Edwidge Danticat (2017), a collection of interviews with the author, and the volume N arrating History, Home, and Nation: Critical Essays on Edwidge Danticat , edited by Megan Feifer, Maia Butler, and Joanna Davis-McElligatt (forthcoming). All of these works mark the beginning of a serious, engaged scholarship on the fi ction and nonfi ction writings of Edwidge Danticat and augment hundreds of literary critical essays about her work. Th e Bloomsbury Companion to Edwidge Danticat builds on this literary reception and will be the only comprehensive volume on her writings that tackles the literary oeuvre in its entirety, cross-genre, and organized around myriad themes in her corpus. Providing an extensive and comprehensive overview to the fi ction and nonfi ction oeuvre of Haitian American writer Edwidge Danticat, the book deploys literary, cultural, historical, political, and social analyses to her literary corpus; and the book is organized around key themes and concepts in her body of work. Th ree key features of Th e Bloomsbury Companion to Edwidge Danticat include comparative and multidisciplinary analyses of Danticat’s literary oeuvre; an expansive engagement with multiple genres—short stories, essays, novels, memoirs, and young adult and children’s literatures—and the full corpus of her writing; and an encyclopedic and comprehensive companion to her literary corpus and its location within Haitian history, folklore, religion, and politics, as well as within circum-Caribbean, inter- American, and hemispheric frames. Structure of the Book In Part I, “Literary Beginnings,” we include (following this editors’ introduction) a nonfi ction essay by Edwidge Danticat (“ ‘All Geography Is within Me’: Writing Beginnings, Life, Death, Freedom, and Salt”) and an interview with the author by Nadège T. Clitandre (fi rst published in her 2018 monograph Edwidge Danticat: Th e Haitian Diasporic Imaginary ). Discussing a wide range of issues and authors, Clitandre and Danticat address the literary infl uences on her own fi ction, the political and philosophical problems confronted in her nonfi ction, the importance of mentors and representation for women and girls, and myriad other ideas. In the nonfi ction essay, “ ‘All Geography Is within Me’: Writing Beginnings, Life, Death, Freedom, and Salt,” Danticat explores the impact of literary imagination, geography, and the relations to life, death, survival, and experience in her homeland Haiti. Danticat also probes the literary infl uences of Zora Neale Hurston and others on her own literary imaginary, inherited genealogies, and imagined geographies. Part II is entitled “On Violence and Violated Bodies: Biopolitics in Danticat’s Texts.” Th e chapters included in this second section are by contributors Judith Misrahi-Barak, Myriam 4 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 44 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 5 Introduction J. A Chancy, and Jana Evans Braziel. Judith Misrahi-Barak’s chapter, “Reconstructive Textual Surgery in Danticat’s Krik? Krak ! and Th e Dew Breaker ,” foregrounds literary poetics and body politics through the concept of biopolitics , a term fi rst introduced by Michel Foucault and later elaborated by Giorgio Agamben, Achille Mbembe, Sibylle Fischer, and myriad other political theorists, philosophers, and cultural critics. Tying the concept of biopolitics and tortured, maimed, mutilated, fragmented bodies or body parts to Danticat’s textual forms, particularly the short story and short story cycle, Misrahi-Barak asserts that the author performs a “reconstructive textual surgery” that reconstitutes the body and the body politics, however injured and wounded. Beginning with a powerful anecdote and a cautionary tale about racial, ethnic, and immigrant presuppositions, Myriam J. A. Chancy, in her chapter “ ‘I Might Lose All My Life’: Brother, I’m Dying and (Black) Immigration Discourse in the United States,” tackles the geopolitics and imaginary terrains of contemporary immigrant politics in the United States and in Canada. From this account, and drawing from and textually analyzing Danticat’s literary memoir, B rother, I’m Dying (2007), she stages a literary debate about contemporary immigrant politics and policies in North America, specifi cally the United States and Canada, foregrounding diasporic approaches that center on Haitian immigrant experiences in the two countries. Chancy importantly reminds readers that Black biopolitics in North America need to incorporate African and Caribbean diasporic experiences, and that not doing so demonstrates the devaluation of Black existence in the body politic. In the chapter, “Alleys, Capillaries, Th orns: Th e Violated Terre-Natale of Ville Rose,” Braziel explores the ville imaginé of Ville Rose in Danticat’s literary oeuvre as the historical ground of sexual violence in Haiti. Rereading all of Danticat’s literary texts for their treatments of sexual violence, maternal death, and dead babies, Braziel illustrates the ways in which these violences are foundational not only for understanding Haiti’s entangled histories of slavery, colonial domination, and rape but also for understanding the ways in which Danticat’s literary reimaginings of these histories create alternative spaces for women and children within that violated historical ground: by demonstrating the violences that transpired, the author points to women and children’s absences, or presences as violated terrains, and demonstrates that Haitian futures must unearth these violated terrains and create new spaces—not just imagined spaces but ones that are social and political and economic—for women and children as historical actors and political agents. Part III is entitled “On Death and Dying: Necropolitics in Danticat’s Texts” and includes chapters written by Simone A. James Alexander, Anne Brüske, and Marie-José Nzengou-Tayo. Simone A. James Alexander, in her chapter “Losing Your (M)Other: Danticat’s Narratives of Un/Belonging and Un/Dying,” foregrounds Danticat’s literary and philosophical engagements with death and dying: in the chapter, Alexander adopts Danticat’s ideas of “living dyingly” (from Th e Art of Death ) to conceptualize the spiritual and transcendent terrain of dying through the term “necro-transcendence.” For Alexander, necro-transcendence captures the processes of un/belonging and un/dying; and she analyzes death through this lens in several literary works by Danticat—B reath, Eyes, Memory ; Th e Farming of Bones ; Th e Art of Death ; and Untwine —as well as draws parallels to literary treatments of death and dying in works by American literary authors, particularly Toni Morrison’s S ula and Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.” Further developing the discussion of Danticat’s literary preoccupations with death and dying, Anne Brüske, in her chapter “L ò t bò dlo : Producing Haitian Spaces of Death and 5 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 55 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 6 The Bloomsbury Handbook to Edwidge Danticat Diaspora in Danticat’s Th e Dew Breaker , examines the ways in which death (as theme and trope) informs not only the content of Danticat’s texts but also the author’s “aesthetic form.” Brüske draws on Th omas Macho’s concept of “presence in absence” to do so; and she focuses her analyses of death and dying as aesthetics in Th e Dew Breaker , though she also surveys the “spaces” of death throughout myriad texts— Th e Farming of Bones ; Create Dangerously ; Claire of the Sea Light ; and Th e Art of Death . Using Danticat’s Haitian Kreyòl phrase, “lòt bò dlo,” “the other side of the water,” Brüske explores the mythical spaces of death in diaspora, centering her reading through Vodou understandings of death and the spaces of death. Extending discussions of death and dying in Danticat’s oeuvre, Marie-José Nzengou-Tayo, in her chapter entitled “Death and the Maiden: Writing Death in Danticat’s Fiction,” delves into literary treatments of death as “exorcism” of the “fear of death,” as the author herself fi rst introduces in Th e Art of Death . Probing this recurrent theme—death, dying—in several diff erent literary texts (B reath, Eyes, Memory ; Krik? Krak! ; Th e Farming of Bones ; Th e Dew Breaker ; and Claire of the Sealight ; as well as in Th e Art of Death) , Nzengou-Tayo off ers readers a “typology” of death in Danticat’s literary corpus as well as its role in narration and in the writer’s narrative forms. Nzengou-Tayo thus builds on what Brüske defi nes as the “aesthetics” of death in Danticat’s literature. Finally, and by focusing on processes of mourning, grief, and bereavement, Nzengou-Tayo, like Alexander, attends to the philosophical dimensions of death and dying in Danticat’s work. Part IV, entitled “Tifi ak Fanm, Girls and Women,” foregrounds the relationship of women and girls through feminist lenses and includes contributions by Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw, and Cara Byrne. Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, in her chapter “ ‘Somebody, Anybody Sing a Black Girl’s Song …’: Danticat and Haitian Girlhood,” centers the lives and lived experiences of Black girls in Danticat’s literary texts. Foregrounding analyses of B reath, Eyes, Memory and Claire of the Sea Light , Jean-Charles examines the ways in which Danticat writes for and about tifi , girls in Haiti and in Haiti’s diaspora. Building on the interdisciplinary fi eld of Black girlhood studies, Jean-Charles demonstrates how Black girls are too oft en rendered invisible culturally, historically, socially, and politically, and off ers, through Danticat, a counter-narrative that places Black girls at the literary and imaginary center. In “Th e Good Daughter: Danticat’s Migrating Memories,” Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw takes up the theme of t ifi ak fanm , girls and women, through the fi gure of the daughter. By focusing on the “daughter” as a literary, philosophical, and historical trope (as do other French and francophone writers, notably Simone de Beauvoir in M é moires d’une jeune fi lle rangé e , translated into English as Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter ), Walcott-Hackshaw off ers literary critical readings of two short stories—“Th e Book of the Dead” and “Sunrise, Sunset”—and of Th e Art of Dying , the book of essays in which the writer/daughter philosophically meditates on the death and dying of her own mother. Th roughout the chapter, Walcott-Hackshaw asks how daughters understand what is meant by being a good mother, a good daughter, and also how to lose a father—all experiences that must be meditated on and in relation to memory and migration, the memories of migration, and the migration of memories. Cara Byrne, in her chapter “ ‘I Am the One Telling It’: Resilient Children, Familial Bonds, and Haitian Heritage in Danticat’s Picture Books,” off ers a comprehensive overview of Danticat’s contributions to children’s literature: Byrne, in the chapter, discusses all of Danticat’s children’s books—E ight Days ; Th e Last Mapou ; Mama’s Nightingale ; and My Mommy Medicine —and illustrates the author’s important contributions to diversifying the range of books available to 6 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 66 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 7 Introduction children that candidly talk about diffi cult topics—race, immigration, detention, and separation. Th e chapter thus adds nuance and depth to our understanding of Danticat’s literary oeuvre by foregrounding the writer as writer of children’s books. Byrne’s chapter thus beautifully concludes the section on tifi ak fanm. Part V, entitled “Ecri Angaje: Political Writing: Danticat as Public Intellectual,” includes contributions written by Edwidge Danticat, Anja Bandau, and by Maia Butler and Megan Feifer. Th e section opens with Danticat’s memorial essay marking the tenth anniversary of the 2010 earthquake. Th e essay, “Haiti Faces Diffi cult Questions Ten Years aft er a Devastating Earthquake,” fi rst published in the N ew Yorker , asks readers to consider the progress (or lack of) in the decade since the devastating natural disaster in the country. Placing the earthquake in the ongoing struggles against grinding poverty, international interference, political corruption, and mobilized resistance, Danticat repeatedly and heuristically asks her readers, “What if …?” What if the earthquake had not killed over three hundred thousand Haitians; what if the international community had involved Haitians in the reconstruction process; what if the international funds had not been squandered? Centering on the idea of “memorial art” and the praxis of politically engaged writing in the face of disaster or mass destruction, Anja Bandau (in her chapter “C reate Dangerously : A Poetics of Writing as Memorial Art; the Text as Echo Chamber”) analyzes Danticat’s nonfi ction collection of essays: for Bandau, Danticat’s nonfi ction form of “creating dangerously” (adopted from Albert Camus) must be understood as diasporic, written from a migratory position in relation to the homeland and the site of destruction or ruin. Bandau also theorizes, following Danticat herself and Clitandre (in E dwidge Danticat: Th e Haitian Diasporic Imaginary ), the “echo chamber” as a politicized, literary site of polyphonic voices, testimonials that echo, reverberate, and reiterate the semiotic registers of trauma, including speechlessness or aphasia. Doing so, Bandau also importantly brings Danticat into echoing conversations with other Haitian writers, notably Yanick Lahens, Dany Laferrière, and Kettly Mars. Maia Butler and Megan Feifer, in their coauthored chapter “Haiti’s Past, Present, and Uncertain Future: Danticat’s N ew Yorker Column as Platform for Public Intellectualism,” discuss Danticat’s role as a public intellectual and as a politically engaged nonfi ction writer. In this role, Danticat regularly weighs in on critical, contemporary issues, particularly those impacting her homeland Haiti and Haiti’s diaspora in the United States, as well as contributing short stories and other fi ction pieces in the New Yorker , one of the most infl uential literary and highly circulated cultural journals published in the country (the United States). For Butler and Feifer, Danticat manifests in these regular contributions the role of “engaged citizen,” a guiding and vital voice for her readers around salient issues impacting citizenship and the country, including race, race politics, immigration, presidential politics, mobilized resistances, and the minority perspectives and vibrant spaces of American literatures. Part VI is entitled “Food, Haiti, and Haitian Culinary/Literary Inheritance” and includes chapters by Valérie Loichot, Wilson C. Chen, and Robyn Cope. Reprinted from Meridians: Race, Feminism, Transnationalism , Valérie Loichot’s chapter “Edwidge Danticat’s Kitchen History” marks an important foray into the interdisciplinary spaces of food studies, literary culinary studies, and the importance of food and cooking to women’s writings in the francophone traditions, here Haitian. Focusing on the roles that food and cooking play in women’s lives, in Haitian heritage, and as a metaphor for writing, particularly in Danticat’s fi rst short story collection Krik? Krak! and in her debut novel B reath, Eyes, Memory , Loichot argues that the 7 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 77 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 8 The Bloomsbury Handbook to Edwidge Danticat diasporic kitchen is a feminist space of memory, remembrance, legacy, heritage, and creation in words and in food. Loichot’s original essay (published in 2006) appears here with a new “Epilogue: Kitchen History, Twenty or So Years Later …” Further developing this critical, culinary line of inquiry, Wilson C. Chen (in his chapter “ ‘A People Do Not Th row Th eir Geniuses Away’: Danticat’s ‘Kitchen Poet’ Literary Antecedents”) opens by responding to Alice Walker’s call from “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” for literary excavation of lost, maternal genealogies. Quoting Walker’s essay in his title (“A People Do Not Th row Th eir Geniuses Away”), Chen further probes the importances of food, culinary traditions, cooking, and kitchens in Danticat’s literature and also seeks out her “kitchen poet” literary antecedents, primarily (in Chen’s reading) Zora Neale Hurston, Paule Marshall, and Walker. Chen particularly attends to the literary infl uence of Marshall and her essay “From the Poets in the Kitchen.” Robyn Cope, in her chapter “Scattering and Gathering: Danticat, Food, and (the) Haitian Experience(s),” also probes the interdisciplinary and diasporic spaces of food, cooking, and culinary metaphors for immigration and memory. Building on the praxes of “scattering” and “gathering,” which emulate diasporic separation and transnational closing of distance, Cope examines the generational and geographic divides that Danticat writes across. Drawing parallels to Jacques Stéphen Alexis, Cope also underscores the ways that Danticat’s “scattering” and “gathering” through food and culinary traditions also intersections with the Haitian literary tradition of “marvelous realism.” Part VII is entitled “Th eoretical Approaches” and includes chapters by Kyrah Malika Daniels, Kristina Gibby, Carine Mardorossian, and W. Todd Martin. Kyrah Malika Daniels, in her chapter entitled “S ea, Stone, Sky, and Cemetery : Vodou’s Divine Nature and Religious Archetypes in Danticat’s Krik? Krak! and A ft er the Dance ,” explores the role that Vodou spiritualism, ritual, and folklore play in the writer’s literary imagination and moral compass. Analyzing the short stories in Krik? Krak! alongside the nonfi ction travel narrative Aft er the Dance , which is about Kanaval (Carnival) in Jacmel, Daniels off ers a brilliant and compelling analysis of Vodou as integral to the moral and spiritual fabric of Danticat’s literary imagination. Daniels also incorporates insights from an interview with the author to further underscore the essential importance of Vodou not only for Danticat but also for Haitians in the country and in diaspora. In “ ‘So Much Had Fallen into the Sea’: An Ecocritical Approach to Danticat’s Claire of the Sea Light ,” Kristina Gibby reads Danticat’s most recent novels through environmental lenses. Proceeding from ecocriticism and environmental humanities approaches for analyzing literary texts, Gibby contextualizes Danticat’s fi ction within the interdisciplinary fi eld of Caribbean environmentalism. Asserting the importance of environmental approaches to Haiti, Haitian, and Haitian diasporic literatures, Gibby places Danticat’s novel alongside literary texts by other Caribbean writers (Derek Walcott, Jamaica Kincaid, Édouard Glissant) who delve into the environmental terrains of the archipelago. Carine Mardorossian, in her chapter “ ‘Aha!’: Danticat and Creolization,” positions Danticat as a writer who presumes her location as one of creolization, hybridity, and diaspora—and writes from this politics/poetics of location and relation. Whereas an earlier generation of Caribbean and Caribbean diasporic writers felt the need to defend this positionality, Danticat, like an entire younger generation of writers and artists, begin from this mixed point of departure and thereby create relationally and transnationally across previously held national divides. 8 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 88 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 9 Introduction Doing so allows for greater infl uence and impact in multiple points of departure, location, and myriad arrivals, as well as liminal spaces in between. In a similar theoretical vein, W. Todd Martin addresses cultural inheritance, fragmentation, memory, and remembrance as creolized praxis in and through the short story form in his chapter “Memory and the Possibilities of the Short Story Sequence in K rik? Krak! ” For Martin, as for Misrahi-Barak and Mardorrosian, the short story form and the story cycle manifest fi ction written at diasporic distance: a process of recreating through memory, language, and shards of sutured meaning; and the short story, in its recurrent characters and narrative fragments, works to recreate and suff use with meaning what has been lost. Part VIII is entitled “Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Transnational Hispaniola” and includes chapters by John D. Ribó and Ramon Ant. Victoriano-Martinez. John D. Ribó, in “ ‘Neither Strangers nor Friends’: Transnational Hispaniola and the Uneven Intimacies of Th e Farming of Bones ,” examines the histories of racism, racial violence, and linguistic divides between the Dominican Republic and Haiti and analyzes Danticat’s 1998 novel as a writerly intervention in the vexed relations and borders between the two countries. From this analytical and critical point of departure, Ribó returns to the border wars between the two countries through the recent points of cultural, historical, and political collaboration through the Transnational Hispaniola collective and movement. Transnational and diasporic activists and scholars, operating from a position of shared Afro-Latinidad and Latinx studies, have assiduously labored to heal the trauma and historical wounds. While some Haitian American cultural critics, notably Ayana Legros, declare and champion a Latina identity, others, saliently, Nathalie Cerin, refuse such identity claims, preferring to remain resolutely Haïtienne. Foregrounding the debate between Legros and Cerin, Ribó argues for a similar tension manifest in the novel Th e Farming of Bones between Valencia and Amabelle. In the end, due to Valencia’s refusal to be historically accountable for the violence, the Haitian massacre, Amabelle refuses intimacy and affi liation with her. As Ribó concludes, Dominicans must step forward, accept historical complicity, and acknowledge past and present violences before healing between the two countries can occur. Th e Transnational Hispaniola is one eff ort toward that healing. Ramon Ant. Victoriano-Martinez, in the chapter “ ‘Walk Too Far in Either Direction and People Speak a Diff erent Language’: Navigating Hispaniola in Danticat’s Th e Farming of Bones ,” places ongoing racial tensions and border divides between the Dominican Republic and Haiti in the context of earlier historical violences, including the 1937 “Parsley” Massacre. Placing Danticat’s violence in conversation with other political, literary, and legal writings in the Dominican Republic, Victoriano-Martinez traces the long history of legislative, material, and civic violence against Haitians living in the DR. Part IX, “Critical Sources,” concludes the volume and includes a bibliography of writings by Edwidge Danticat, a bibliography of literary criticism on Danticat, and the biographical notes for all contributors, including the author and the editors. 9 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 99 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 1111 CHAPTER 1 “ALL GEOGRAPHY IS WITHIN ME”: WRITING BEGINNINGS, LIFE, DEATH, FREEDOM, AND SALT Edwidge Danticat 1 Th is past June I was in Haiti in part for the opening of a library in a southern town called Fond- des-Blancs. Fond-des-Blancs, which literally means “Th e Fountain of the Whites,” is mostly known for being home to a large number of people of Polish lineage, the descendants of soldiers from a Polish regiment that switched alliances from the French armies they were fi ghting alongside in nineteenth-century Haiti to join the Haitians in their battle for independence from France in 1804. Th e mutinous Polish soldiers who ended up settling in Fond-des-Blancs were the only whites and foreigners who were granted Haitian citizenship aft er Haiti became the fi rst black republic in the Western hemisphere in 1804. Th e library we were there to celebrate had been started by a nonprofi t called Haiti Projects, which was run by an acquaintance of mine whose mother is American and whose father is Haitian. Th e opening-week program included writing workshops and conversations with writers. I took part in a conversation and writing workshop with the Haitian novelist and short-story writer Kettly Mars. Our moderator, a Haiti-based educator named Jean-Marie Th éodat, asked each of us to read both the beginning and the end of one of our short stories, then explain to the group of twenty-fi ve or so eager teenagers why we had chosen to begin and end that story the way we had. If you have ever spoken to a group of teenagers, you know how intimidating it already is to explain anything to them, but this was a bit extra intimidating for me. It is much easier to explain or elaborate on an ending than a beginning. For endings, you can always say that it ended this way because it had begun t hat way. Or it ended that way because something popped up in the middle that led me there. Beginnings have a much bigger burden and are oft en less clear. In the beginning was the Word, the Good Book tells us. And perhaps the Word—or the Words—was, were … Once Upon a Time, Il était une fois or Te gèn yon fwa or Krik? Krak! 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 1111 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522 12 The Bloomsbury Handbook to Edwidge Danticat I feel the same dilemma right now while trying to trace the geography, or cartography, both internal and external, that has brought me from my own beginnings to this moment. Once upon a time, a little girl was born in Haiti during the middle part of a dynastic thirty- year dictatorship. Her parents were poor, though maybe not as poor as others. My parents didn’t get very far in school because their parents could not aff ord it. My mother was a seamstress. My father, a shoe salesman and a tailor. When I was two years old, my father left Haiti and moved to the United States to look for work. Two years later, my mother joined him and left me and my younger brother, Bob, in the care of my aunt and uncle in Port-au-Prince. One of my earliest childhood memories is of being torn away from my mother. On the day my mother left , I wrapped my arms around her legs before she headed for the plane. She leaned down and tearfully unballed my fi sts so that my uncle could peel me off her. As my brother dropped to the fl oor, bawling, my mother hurried away, her tear-soaked face buried in her hands. She couldn’t bear to look back. If my life were the short story I was asked to explain the beginning of in that writing workshop with the teenagers in Fond-des-Blancs, this might have been my chosen beginning, the most dramatic one I can remember. Aft er all, as the French-Algerian writer Albert Camus wrote, a person’s art is “nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart fi rst opened.” Since I was too young to remember my father leaving Haiti for the United States, my mother’s departure was one of the fi rst images in whose presence both my heart and my art fi rst opened, an art and a heart that suddenly expanded beyond geographical confi nes and also made me realize that one can love from both near and far. In Haitian Creole when someone is said to be “l ò t bò dlo ,” on the other side of the water, it can either mean that they’ve traveled abroad or that they have died. My parents were already lòt bò dlo, on the other side of the waters from me, before I fully even knew what that meant. My desire to make sense of this separation, this l ò t bò dlo -ness, is one of the things that brought me to the internal geography of words and how they can bridge distances. One way I used to communicate with my parents was through letters. We spoke on the phone once a week while sitting in a telephone booth, where we had a standing appointment every Sunday aft ernoon, but we also communicated through cassettes that we sent back and forth with people who were traveling between New York and Port-au-Prince. We wrote letters too. Every month my father would send us a half-page letter composed in stilted French to off er news of his and my mother’s health as well as details on how to spend the money he and my mother wired for my and my brother’s food, lodging, and school expenses. When my parents’ letters and cassettes found their way to me from Brooklyn to Port-au- Prince, I again realized how words—both written and spoken—can transcend geography and time. My mother could tell me stories—once upon a time—in my mind. And I knew, because she later told me this, that she was imagining every day of my life, then would dream of whatever indispensable thing she thought I needed to know, things she believed that only she could tell me. Th e way she imagined my life in her absence was sometimes better and sometimes worse than what was actually happening to me at ages four, fi ve, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven and twelve, but we were constantly alive in each other’s imagination. And because my mother did not write letters and because I did not ever want to forget the things I wished my mother were telling me, the stories I wish she were telling me, I tried to write them down in a small 12 99778811335500112233552266__ppii--444488..iinndddd 1122 1111--DDeecc--2200 1100::3300::5522