The Biblical Archaeologist - Vol.57, N.4 PDF

Preview The Biblical Archaeologist - Vol.57, N.4

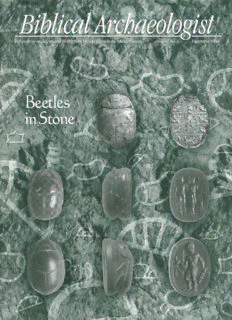

NL. ~r It ?~ --S --4 ICI ..A. Biblical Archaeologist Perspectiveosn theA ncienWt orldfr omM esopotamtioa t heM editerranean Volum5e7 Numbe4r A Publicatioonf theA mericaSnc hoolso f OrientaRl esearch Decembe1r9 94 186 Beetles in Stone: The EgyptianS carab WilliamA . Ward , .. A commonb eetlep layeda n uncommonr olei n ancientE gyptianc ulture. Extraordinariflrye quenat s ana rtisticm otif,t hed ungb eetle'sn amea nd imagep ortrayedth ei deao f birtho, f life,a nde speciallyth es econdb irth intoe ternael xistenceW. hatw as so captivatinagb outt hed ungb eetle?A s a powerfual muleta, seal,o r pieceo f jewelryt,h es caraba lsob oasteda tremendoups opularityb eyondE gyptS. uchp opularityp resentsa rchaeol- !:i ogy withi ntriguingb, utc omplexp ossibilitiefso rt akingt hem easureo f these" beetleisn stone." 203 The Fortressesa t 'En ;IaHeva RudolphC ohen page 186 Excavationasr eb eginningto uneartha singularlyim pressivese rieso f superimposedfo rtresbs uildingsn earo ne of them osta bundanstp ringsi n theA rabahV alleyo f IsraelF. iveo ccupationle velss tretchfr omt heB yzan- tinea ndE arlyI slamicP eriodst hrought heR omana nd NabataeanP eriods all thew ay to thee ighthc enturyo f theI ronA ge.L ocatedst rategicallayt thei ntersectioonf routes,E nI Hasevbae gani ts lifea s a royalo utposts o significantth ati t maye venh avel efta memoryo f its name. 215 What's in a Name: The Anonymity of Ancient Umm el-Jimal Bertd e Vries r.I "Motheorf Camels"is onlyo ne readingo f the modemn ameo f thiss tark and intriguingb asalt-buislte ttlementI.t sa ncientn ame?N oneo f thet anta- lizingp ossibilitieisn thel iteraryso urcesc heckso ut.T hea ncients itew ill havet o remaina nonymousw, itho nlyt her esidueso f itsi nhabitantsli'v es witnessingt o theiri dentity. page 203 220 The WomanQ uestion and FemaleA scetics Among Essenes LindaB ennettE lder Weren ott heE ssenesa tQ umranc elibatem ales?T hep resumptioonf a celi- batem alep opulationo n thes horeso f theD eadS eac ontinuetso rules chol- arlyi maginationsB. utw hata boutt hes keletonso f femalesin thec emeter- ies?A nd whata boutt het extuarl eferencetso liturgieisn volvingw omen? Do nota ll thes ignsp ointt o thep resenceo f femalea sceticsa tQ umran? CP 236 News, Notes, and Reviews TheW allso fJ erusalemW. ithi ts continuouus rbano ccupatione,x tending backt o the2 0thc enturyB CEth, ec ityo f Jerusalemof fersa cruciacl ase-study in urband evelopmenat nds patiasl ymbolismA. new,d etaileda nalysiso f its successivew allsa ndg atesb y G.J .W ightmanre vealsJ erusalemc'so m- plexa ndo ftenb loodyh istoryw rittenin thec ity'sm ortara nds tone. On the cover: Numerous schematic representationso f Egyptiand esign scarabs animate the backgroundf or three examples of the modification of the scarab outside of Egypt:t he highly ornamental Phoenicians carab (top) and two Europeane xamples-Etruscan and Greeks carabsw ith obvious motifs from the classical repertoire. Fromth eE ditor Biblical Archaeologist The last two years have seen BA achieve the transition to full electronic PeMrsepseocptoivtaeosmn titaho e tAh enM cieedniWtt eorrraldnfr eoamn production. Every image and every piece of text of volume 57-from the jots and tittles to the jugs and tells-made its way to the printer on disk. Elec- Editor David C. Hopkins tronic production has offered the possibility of innovative layouts and en- ArtB DoiroekcRt ore viRewobE erdti tDo. rM Jaenmche,s C T.o Mp Doyeseigrn hanced visual presentations of research findings. BiblicalA rchaeologisth as Editorial Assistant Mary Petrina Boyd become a more effective vehicle of communication. Editorial Committee This issue's table of contents manifests the diversity that has become the JefferyA . Blakely Douglas A. Knight magazine's hallmark. Articles roam from the scarabs of Egypt to a spring-fed Elizabeth Bloch-Smith Mary Joan Leith strategic site in the Arabah Valley to the shores of the Dead Sea to the fringe Betsy M. Bryan Gloria London of the Arabian Desert. Despite their geographical, topical, and chronological J.P.D essel Jodi Magness variety, the articles are linked by their preoccupation with the classic ques- REronneasltd SS. .F Hreernidchels GGaeertaalndo L P. Maluamttbinog ly tions of archaeology of the historic periods, namely: typology and toponymy. Richard S. Hess Paul Zimansky The first essay, Ward's presentation on Egyptian scarabs, eventuates in a con- Kenneth G. Hoglund sideration of their typological history. This multifarious history of scarab style, Subscriptions Annual subscription rates are in turn, provides helpful links between Egyptian historical periods and $35 for individuals and $45 for institutions. There archaeological phases of Bronze Age Palestine. Attention to numerically sig- pish ay sspiceaclilayl cahnanluleanl greadte, oofr $ u2n8e fmorp tlhooyseed .o vBerib 6li5c,a l nificant groups of scarabs underlies the typology's usefulness as a chrono- Archaeologisist also available as part of the benefits logical guide. of some ASOR membership categories. Postage Toponomy links Cohen's and de Vries' pursuits at distant locations along for Canadian and other internationala ddresses is ancient Palestine's major north-south line of communication. Cohen is con- aAnS OadRd iMtioenmabl e$r5sh. Pipa/y mSuenbtssc rsihboeur lSde rbvei cseesn, tP t.oO . vinced that the ancient name of his site is preserved in Roman/Byzantine as Box 15399, Atlanta, GA 30333-0399 (ph: 404-727- well as biblical literary sources. For de Vries, the ancient name of Umm el- 2345; Bitnet: SCHOLARS@EMORYUI).V ISA/ Jimal remains unknown and probably unknowable. The royal and imperial Mastercard orders can be phoned in. interests that sponsored the series of fortresses at cEn Haeeva apparently did Back issues Back issues can be obtained by call- ing SP Customer Services at 800-437-6692o r writ- not come into play at Umm el-Jimal's location just a few kilometers off the via ing SP Customer Services, P.O. Box 6996, Al- ilova. For their part, ancient record keepers and map makers stuck to the pharetta, GA 30239-6996. main roads and primary stations. Perhaps epigraphic finds will resolve the Postmaster Send address changes to Biblical toponomic issues for the sites. Barring that, their inhabitants will be known ArchaeologisAt, SOR Membership/SubscriberS er- vices, P.O.B ox 15399,A tlanta, GA 30333-0399. only through the archaeologically recovered and reconstructed detritus of Second-class postage paid at Atlanta, GA and their lives, only through stratigraphy, typology, and sherd counts. additional offices. The counts have always been there, as Elder recognizes in her treatment Copyright @ 1994 by the American Schools of of women ascetics at Qumran. The sheer number of females and children Oriental Research. buried in Qumran's cemeteries unbalances the long-tenured view that its res- Correspondence All editorial correspondence should be addressed to BiblicaAl rchaeologist4,5 00 idents were exclusively celibate males. Elder calls attention as well to texts Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC among the Dead Sea Scrolls that offer entry into women's participation in the 20016-5690 (ph: 202-885-8699;f ax: 202-885-8605). life of the Qumran community. The fact that these data have not been widely Books for review should be sent to Dr. James C. Moyer, Department of Religious Studies, South- heeded makes us conscious of how deeply what archaeologists believe to be west Missouri State University, 901 South worthy of recording impinges upon interpretation. Consciousness about National, Box 167,S pringfield,M O 65804-0095. what one credits with reality, i.e., epistemology, must accompany the funda- Advertising Correspondence should be ad- mental pursuits of collecting, counting, and classifying. The post-modern era dressed to Sarah Foster,S cholars Press, PO. Box 15399, Atlanta, GA 30333-0399 (ph: 404-727-2325; recognizes the continuous shaping and re-shaping of the world of interpreta- fax:4 04-727-2348).A ds for the sale of antiquities tion. Archaeological "collecting," "counting," and "classification" do not suf- will not be accepted. fice in this world, but they do supply the foundation for constructing a past that aims at coherence and correspondence to the recoverable data. qBuibalritcearAll yr( cMhaaeroclho,gJ ius(ntI Se,S SNep 0t0e0m6-b0e8r9,D 5)ei sc epmubbleirsh) ed This larger world of multiple interpretations and perspectives for reading by Scholars Press, 819 Houston Mill Road NE, Atlanta, GA 30329, for the American Schools of the data finds representation in the easy structuring and re-structuring of Oriental Research( ASOR),3 301 North Charles text and graphics made possible by BA's computer production. Eventually Street, Baltimore,M D 21218. Printed by Cadmus these electronic particles find a fixed form as the ink of the pages of the journal. JournalS ervices, BaltimoreM D. Hopefully, the images of jots and jugs offer insight in our encounter with the past and present. OF 0? `A1P4{ Htarw lL Beetles ile a biologist may appreci- Scarab Origins, in ate the beauty of the beetle's Manufacture, and Use physical structure and the Stone: The wonder and precision of its life cycle, Origins to most of us the beetle is simply a pest, Around 2500 BCEa, class of small stone certainly not a creature to be endowed design amulets began to appear in Egyptian with awe and respect. The Egyptian Egypt, found primarily with women attitude toward the beetle was quite and children buried in cemeteries of the Scarab the opposite of the attitudes of most ordinary people of Egypt. The earliest people today.1T he beetle is an extraor- examples are shaped like a tiny pyra- dinarily common motif in Egyptian art, mid and have geometric and animal By William A. Ward it was honored in religious thought, designs engraved on the bottom sur- and the name of the beetle and its pic- face. As time went by, the shape of these ture portrayed the idea "to come into objects changed into circularb ases with existence" in the Egyptian language a pierced knob on the back, the form and script. The Egyptians honored the which caused early archaeologistst o call beetle because it represented some- these objects" buttons eals."S hortlya fter The male beetle makes a ball of dung to thing that was deeply meaningful this, design amulets began evolving into be buriedj ust under the surface and used within the framework of their beliefs objects that retained the circularo r oval later as a food supply.T o rollt his food sup- about the universe. It spoke about the base, but were now carved with backs ply to where it will be buried, the beetle powers they believed controlled that in the form of animal or human heads, balances on its rearl egs, using the front and universe, and reflected thoughts about or whole animal or human figures.2 middle pairt o push the ball. Photograpbhy the Egyptians themselves and their One of these animals was the beetle. S. 1. Bishara.F romW ard 1978:1071. eternal existence. Within a very short time, the beetle be- (cid:127) -- -" - . (cid:127)',,a . , .' ,(cid:127),(cid:127) :,.- . . .r. N, . ~5? ?Yj ) It ?' ???? L L came almost the only back used on this class of object.I t is this final stage of artisticd evelopment that is called the "scarab.3"F roma bout 2200 BCEto late 44 in Egyptian history,s carabsr emained one of the most common objectsm anu- factured in Egypt. Hundreds of thou- Pi 'L? II sands are known in museums around the world. They are found in every ex- C cavation in Egypt and across the ancient 44 " ~ ~ world from Syria to Spain. By the end of 16iIQ 'st its long history,t he scarab had become a universal objecti n the Mediterranean countries and was manufactured in -? lb many places outside Egypt. What was ~i~ created as a small amulet for women and children of the poorer classes of Egypt became an internationalo bject for all classes of people everywhere in the ancient world. Life Cycle of the Dung Beetle But the immediate question is: why the beetle? Or more specifically,w hy one species of this insect, the dung beetle? The female beetle makes an oval ball underground.T he egg is placed in a pouch on this Nothing can be less inspiring to us than ball which becomes the food supply for the larvao nce the egg is hatched. Casualo bservers an army of beetles crawling around a never notice the female's activitya nd can easily attributet he birth-cyclet o the male alone. dung-heap. But the Egyptians saw Photographb y S. I. Bishara.F romW ard1 978: 101. something vitally significanti n that very situation. They saw a vision of rebirth into paradise, the resurrectiono f the 12 3 soul; they saw the daily rebirtho f their most powerful symbol, the sun, as it appears each morning over the eastern horizon. They saw, of course, what they thought was the beginning and the end of the birth cycle of the dung beetle. Time after time, they witnessed the ma- 4 ture beetle rolling a ball of dung, bury- ing this ball under the earth,a nd some fifteen to eighteen weeks later,a new beetle emerging from the ground. But the Egyptians misunderstood the life cycle of the dung beetle. 7 The dung beetle actually makes two balls of dung, one round and one pear- shaped.4T he round ball is simply a food supply tucked away somewhere in the sand for storage in a kind of kitchen pantry.T he pear-shaped ball is the one in which the egg is actually laid. Design-amulets and earlys carabs. Scarabsa re one form of an earlyt ype of object, the de- But this pear-shaped maternal ball was sign-amulet, the earliest (1) having a pyramids haped back. These soon developed into exam- made underground. Casual observers ples with shanks (2) and knobs (3) as well as animal and human figures (4-5). The beetle form, never see it; they see only the round ball or scarab, was one of the latter,f rom the first small ones (6) to the largerm ore elaborate style made on the surface.T his led to the (7). The objects shown here date ca. 2300 to 2100 BCED. rawingsa fter Brunton( 1927; 1948). BiblicalA rchlaeologi5st7 :4 (1994) 187 -y \r I ,/ ---2Z The god Khepri seated in his barka s the personificationo f the morning sun; after a vignette Important Egyptian officials were grant- to Chapter1 7 of the Book of the Dead written during the New Kingdom.K heprii s identified ed the use of a royals ignet ring with which by the symbol of a beetle on his head. The dung beetle (ScarabaeusS acer L),t he model for they could seal documents in the king's the scaraba mulet, was associated with Kheprai lreadyi n the PyramidT extso f the Old Kingdom. name. Here, an unnamed treasuryo fficial of He is frequentlym entioned in the Book of the Dead as being a self-engendered deity who KingT utankhamon( ca. 1336-1327 BCEp)r e- each night creates the morning sun that emerges the next morning. The name Kheprim eans sents such a seal to the Viceroyo f Nubia, "Hew ho comes into existence (by himself);"t hat of the dung beetle/scarabw as kheprer," that Amenhotep, who is identified in this scene which continuouslyc omes into existence (by itself)."D rawingfr omE .N avillel971:p3l.0 . by his nickname-HuyI. n the book of Genesis, Joseph is said to have received such a seal when he became the EgyptianM inistero f misconceptionth ati t is the larger ound up. Whent hel arvab reakso ut of thee gg, Agriculture.F romt he tomb of Amenhotep, balli n whicht he egg is placeda nd from it feedso n them aternabl all.W henr eady no. 40 in the Theban necropolis. Drawing whicht he new beetlei s born.I n reality, to changei ntot hep upals tage,i tb urrows from Newberry, 1906: pl. II. the maleb eetlew orkso n thes urfacet o deeperi ntot hee arth.H erei t carveso ut createt he familyf ood supply,w hile the anotherc hamberin whichi t changes supremes ymbolo f birth,o f life,a nd femalei s undergroundp reparingth e intoa pupa,f eedingo n plantr oots.A fter especiallyt he secondb irthi ntoe ternal nursery. two to threew eeks,i t emergeso n the existenceT. hel ittles tones carabh ad In makingt he roundf eeding-ball, surfacea s a youngb eetle. becomea powerfula mulett o help as- the dung beetleu ses its powerfulf ore- suree ternall ife in paradisea, meaning legs and a spade-likep rojectionin front Symbolic Associations whichw as maintainedt hroughoutit s calledt hec lypeusT. hesea ret he tools and other Uses long historyT. hes carabs ignifiedt he with whichi t worksb y scoopinga nd Observationos f the dung beetlem ade regenerativpe owerso f Atumt he cre- moldingt he raw materiaul ntili t forms by the Egyptiansa rew hatm adet his ator,a nd Re,t he providero f life.A s a ballo f dung aboutf ourt o five times insects o importantto them( Ward1 978: such,i t was a potentt alismani ndeed. its own size.T hisi s the tasko f the male 43-46; de Meulenaere1 972;G iveon Buts carabsa lso had otheru ses. We beetlew ho laboriouslyc ollectst he raw 1974).H erew as a creatureth ate merged now know thatt hee arlyd esigna mulets materialt;h enp ushing,p attings, hap- out of thee arth,a n immediates ymbolo f weres ometimesu sed as seals,f ore x- ing,b uildsu p a near-perfecstp heret hat ther esurrectioonf thed ead.B ecauseth ey ample,o n thec lays topperso f pottery is easilyr olledt o wherei t will be buried misunderstoodth e actualb irth-cycle, jars( Giddya nd Grimal1 979:38-39; in the sand. theya pparentlyth oughto f theb eetlea s 1980:267-68).B y around 2000 BCEt,h e Meanwhilet, he femalel aborsu nder- beingo f a singles ex, male,w ho planted impressiono f a scarabb ecamea com- groundm akingt he pear-shapedm ater- his seed in the roundb allo ut of which mon methodf ors ealingm anyk indso f nalb alli n whicht hee gg is to be laid. cameh is offspringT. heyv erye arlya sso- objectsT. heird esignsw ere impressed Workinga lone,s he burrowsf ourt o ciatedt hism istakenv iew witht hed ivine into thec lay stopperso f potteryv essels, eighti nchesi ntot heg round,d igs out a powert heyc alledK hepriw, ho was a or the mud sealingso n storagec hestso r chambera boutf ouri nchess quare, formo f thes un-godR e,t he morning rolled-upp apyrusd ocumentsS. carabs bringst he rawm ateriailn tot hisc ham- sun rebornb y self-generatioena chd ay.5 useda s sealsf ounde xtensiveu se in gov- ber,a nd createst he pear-shapedb all.A t Theb eetlew as also associatedw ith ernmenta dministratioant all levels.7 theb all'sn arrowe nd, she carefullyc on- Atum,t o whom the creationo f the uni- Witht he advento f theT welfthD ynasty, structsa n oval hollowi n whicht he egg versew as ascribeda, nd who was also therea ppeareda new classo f scarabse n- is laid.T hel ittlec hambera nd the tun- self-engendered.6 gravedw itht hen amesa ndt itleso f kings nel by whichi t is reachedi s thenc losed Thed ung beetlet husb ecamet he and governmento fficialsf romp rime 188 BiblicaAl rchaeologis5t7 :4 (1994) ministers down to humble caretakerso f storehouses. Some officials of the cen- tral government were granted the privi- lege of using a scarab-seale ngraved with the king's name. Since they acted in the king's name, they could thus use the king's name to sign documents. This does not mean that all scarabs engraved with names and titles were used as seals. The scarabb ecame an even more potent amulet for achieving the afterlifew hen it was engraved with a personal name. This identified the I specific individual on an object which Of was intended to help the person gain im- mortality.T his practicew as carriede ven furtherw ith royal names. A king's per- sonal name in itself had important mag- ical propertiess ince the king, while not a god during his lifetime as popularly believed,8 did hold an office which had been created at the beginning of time and which was endowed with divine power. Scarabsn aming especially ven- erated kings were made in bulk, often for centuries after their lifetimes. Such scarabsw ere obtained through visits to royal funeraryt emples as a souvenir of the prayers offered there by an individ- ual on behalf of the royal soul. While the scarab was most commonly used as a talisman to achieve eternal life, it had One group of scarabsn aming Sesos- other uses as well, for example, sealing papyrusd ocuments or as in this case, a Middle King- tris I was made five centuries after his dom wooden wig box found at Lisht. death (Ward1 971:134-36).M any Egypt- ian rulers were so honored long after their lifetimes. Scarabsn aming Thut- mosis IIIo f the Eighteenth Dynasty, for example, were still being made a thou- sand years after he died (Jaeger1 982).A similar practiceh as continued down to the presentd ay in Nubia. A scarabf ound by a local inhabitant often becomes a family heirloom, a kind of a magical '' good-luck piece, passed down from gen- eration to generation.9 The scarab was also used as a piece of jewelry.S tone scarabs in gold or sil- ver ring-mounts are quite common, and scarabsw ere often used as elements in pectorals,b racelets,a nd necklaces (Al- dred 1971;W ilkinson 1971;A ndrews Commoners as well as kings inscribedt heir names and titles on scarabs that were some- 1990).W hile scarabs were thus used for times used as seals. Tot he left is a scarab naming "TheS teward Khnumhotep"o f the Middle decorative purposes, in Egypt they no Kingdoma nd, to its right,o ne naming KingA menhotep IIIa nd Queen Tiyo f the Eighteenth doubt maintained their basic amuletic DynastyN. ote the V-shapedm arkingsc alled the humeralc allosityo n the wing cases of the Eigh- characterT. he horse shoe in America teenth Dynastys carab,a typographicalf eature that was not used before that time. It does not and blue bead in Near Easternc ountries appear, of course, on the Middle Kingdoms carab. Photographcso urtesyo f Daphna The Ben-Tor, are used in the same manner today. IsraeMl useumJ, erusalem. Dr. BiblicalA rchaeologis5t7 :4 (1994) 189 glb~~4 Scarab of the Phoenician tradition, ca. decorated representationo f the beetle itself. ite cloak, the winged sun-disc is taken from 800-700 BCEP.h oenicianc raftsmen, always In this example, the decoration on the back Assyriana rt, and the four-winged scarab is a influenced by Egyptiana rt, produced a new is far more elaborate than on Egyptian Canaanitea daptation of a common Egypt- type of scarab combining Egyptianm otifs scarabs and the design on the base is a mix- ian motif, probably influenced by Hurrian with those of other traditions.T he result was ture of many traditions.T he central figure prototypes. Photos and drawing from Ward often a complicated design and a highly wears an Egyptianh eaddress and a Canaan- 1967:pi. 12:1a nd p. 69. Manufacture Scarabsw ere made of almost any kind of stone, often of glazed composition, or, more rarely of gold, silver, or bronze. The most common material used is universally known as steatite, though it is really a kind of talc (Lucas 1962:155- 56; Richards1 992:5-8). In its natural state, this soft stone is easily carved and engraved, which accounts for its very common use in the manufactureo f scarabsa nd other small objects.O nce the scarab was fashioned, it was plunged into a hot liquid glaze. This accomplished two things: the glaze coating gave a O~ O smooth shiny surface to the object,a nd the intense heat of the glaze altered the chemical composition of the stone through dehydration so that it became ee e very hard. This hardened form is prop- WOE) erly called steatite. The glaze is actually an early form of glass that could be col- ored by the addition of coloring agents. Scarabs were most often given a deep blue or green glaze, imitating the color of the live insect. The second most com- mon material is glazed composition, 4)e often termed faience, frit, or paste; again, this is a form of glass using the same ingredients but in different pro- portions (Lucas 1962:160;W ard 1993:95; Clerc, et al. 1976:24-28). Scarabs engraved with royal names were the center of the design and two examples most often amulets, not seals, and were con- add the name of Amenhotep II( ca. 1427-1401 Scarabs, Scarabs, tinuouslyr e-issuedl ong after a king had died. BCEa)t the top. Theses carabsw ere therefore Everywhere Int his group,a n incorrects pellingo f the name made five centuriesa fter the reign of the king One of the intriguing things about of SesostrisI (ca. 1943-1898 BCEr)u nsd own they honor. Drawingsa fter Ward 1971:fig. 29. scarabs was their popularity outside 190 Biblical Archa'olo(cid:127)'ist 57:4 (1994) Canaanite include Egyptian hieroglyphs and sym- artists adapted bols. Two of these are Keel's jasper- the Egyptian group and the well-known robed Ca- scarabt o local naanite figure. The jasper group (Keel beliefs and en- 1989b)i s characterizedb y stick-figures graving tech- and carelesse ngraving, and all examples niques as earlya s are manufactured from hard stones. the Middle While the standing figures find ready BronzeA ge. One comparisons with Asiatic cylinder seals, such adaptation the jasperg roup scarabs make consis- is the use of sym- tent use of Egyptian symbolism as well. bolism in the The other design-the standing or en- "Omega-group" throned male figure with Canaanite as on nos. 1-4, costume (Schroer1 985)-is obviously representingt he not Egyptian but again includes Egypt- Canaaniteg od- ian symbols as part of the design. dess Astarte. Examplesl ike 5 nos. 5-6 are included in this group as they are engraved in raised reliefa nd show the same crude scarab style. A second group, the "nakedg oddess" of nos. 7-9, por- K4W trays Astarte 7 8 9 herself in a typi- callyC anaanite, but not Egyptian, stance. Drawings after Keel 1989a and Schroer 1989. Egypt. This raises the question of what engraved in raised relief,w hich is not the scarabs ignified in foreign places an Egyptian practiceo n scarabs,a nd and how much this peculiarly Egyptian seems to derive from copying cylinder class of object might be adapted to for- seal impressions. eign ideas and beliefs. Such adaptations We have here, then, a local engraving 5 / 8 are already evident in Middle Bronze technique with a mixed design reper- Age Canaan as shown by Othmar Keel toire of both Asiatic and Egyptian ori- and his colleagues in Freiburg.T wo of gin. The nude goddess shown frontally these adaptations are the Omega-group (Schroer1 989:93-121)i s clearly a west and the nude goddess motif. The Asiatic motif with prototypes on cylin- Other Canaanite adaptations of the Omega-group (Keel 1989a)t akes its der seals and the common Astarte Egyptian scarab include a series done in a name from the prominent symbol in the plaques. Showing human or divine fig- local engraving technique, the "Jasper- design resembling the Greek letter.B oth ures frontallyr uns contraryt o the Egypt- group," nos. 1-4. Nos. 3-4, however, while this symbol and the symbol that usually ian practiceo0s o that, in this case, both carved in this Canaanites tyle are local copies accompanies it are said to representa the subjectm atter and the method of of purelyE gyptiand esigns. Nos. 5-8 repre- Canaanite fertilityg oddess, possibly representationa re Canaanite rather sent the "toga-wearer"g roup, a royalf igure Astarte.T he symbols find their proto- than Egyptian. in Canaanitec ostume, based on prototypes types in the cylinder seal traditionso f The sources of other motifs are not as in Canaanitea nd Syriana rt. Drawingasf ter Mesopotamiaa nd Syria.T he designs are clear as these since they almost always Keel 1989b and Tufnell1 984 BiblicaAl rchaeologis5t7 :4 (1994) 191 The lattert wo scarabg roups present a problem encountered with many scarabsa nd other objects del found outside Egypt:w hat is the purpose of the use of Egyptian symbolism in a clearly foreign context? In other words, these Egyptian symbols have a particular significance within an Egyptian context. Was that significance the same in a for- eign context, or was the meaning al- Egyptian artistic influence, includingt he piece as it portrayst he scarab with four tered to suit the beliefs of that foreign scarab, is found on jewelry made locally wings, a common foreign adaptation of the context?O r are we here dealing with around the MediterraneanT. hisg old bracelet two-winged flying scarab typical of Egyptian nothing more than symbols which are from Sardinia, dating ca. 700-600 BCEiS, art. The four-winged variantp robablyo rigi- used merely as decoration in an attempt embossed with Egyptianp almettes, lotus nated in Syriau nder the influence of Hurrian to copy admired Egyptian originals? flowers, and the "flyings carab"m otif. The art which used such four-winged figures Keel and his colleagues support the latter proves the non-Egyptiano rigin of the extensively. idea that Egyptian symbolism was al- tered to suit Canaaniteb eliefs. Their scarabso f the so-called Phoenician style ed by hard stones, chiefly jasper and arguments are not convincing, and in MediterraneanE urope, for example carnelian,a nd shows a strong Egyptian these scarabsm ay be merely bad copies at Ibiza,S pain and Tharros,I taly (Fer- influence in the repertoireo f motifs (cf. with no local religious significance. nandez and Padr6 1982;A cquaro, Culican 1968:50-56).11A large portion The same problem of interpretation Moscati, and Umberti 1975).H undreds of such scarabs were manufactured lo- is found in other foreign scarab tradi- were found at Carthage on the North cally and, by indirect evidence, we can tions. In the early first millennium BCE, African coast (Vercoutter1 945).T his point to Carthage,P hoenicia, Rhodes, we begin to find large collections of Phoenician scarab tradition is dominat- Greece, Sardinia,a nd Italy as having workshops where these scarabs were produced on the spot. The Phoenician scarabs tyle was bor- rowed by Greek gem engravers in the sixth century BCEw, ho perhaps learned the art of cutting hard stones from Phoe- 2 3 nician craftsmen. By the end of the fifth century,t he scarab form became much less used as this archaicG reeks tyle grad- ually changed into classical Greek gems (Boardman 1968;B oardmana nd Vol- lenweider 1978).T he Greek scarab style was soon brought to Etruriab y Greek immigrants where a new and distinctly Etruscant radition appears from the sixth to third centuries. This is charac- terized by its widespread use of a deep red carnelian,d ecoration on the edge of the plinth and wing cases, and local engraving techniques (Boardman 1975; Zazoff 1968). Both the Greek and Etrus- can traditions early introduced a design 8 9 10 repertoireo f their own, and the Egyp- tianizing motifs gradually disappeared. Concurrentw ith these Phoenician, Phoenician (nos. 1-7) and Egyptian (nos. Mediterraneanw orld. The scarab evidence Greek, and Etruscanh ard-stone styles, 8-10) scarabs portrayinga scene from the indicates that the popularityo f Isisi n foreign countless other scarabs of steatite and Isis-Osirims yth. Thisa nd many other scenes cultures may have arisen somewhat earlier glazed composition were being manu- from the myth are known from hundredso f than now supposed. Drawingsa fter Ward factured at, among other places, Carth- Phoenicians carabsf ound throughout the 1970b. age, Perachorai n south-eastern Greece, 192 BiblicalA rchaeologis5t7 :4 (1994)