The Biblical Archaeologist - Vol.27, N.1 PDF

Preview The Biblical Archaeologist - Vol.27, N.1

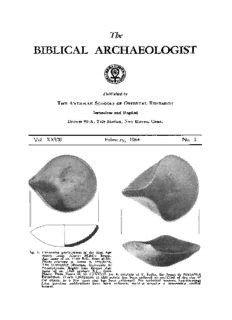

The BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST IWV, IF Published by THE AMERICAN SCHOOLS OF ORIENTAL RESEARCH Jerusalem and Bagdad Drawer 93-A, Yale Station, New Haven, Conn. Vol. XXVII February,1 964 No. 1 :W ,... K~I7 "' -i Fig. 1. Canannite predecessors of the Iron Age t??r?' saucer lamp. Above: Middle Bronze Age lamp of ca. 1700 B.C., from el-Jib. Photo courtesy of James B. Pritchard, The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. Right: Late Bronze Age lamp of ca. 14th century B.C., from Hazor. From Hazor II, pl. CLXXVII, no. 4, courtesy of Y. Yadin, the James de Rothschild Expedition. (Each illustration in this article has been reduced to one-third of the size of the object; in a few cases size has been estimated. For technical reasons, line-drawings from previous publications have been redrawn, making possible a moderately unified format. 2 THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST (Vol. XXVII, The Biblical Archaeologist is published quarterly (February, May, September, December) by the American Schools of Oriental Research. Its purpose is to meet the need for a readable, non-technical, yet thoroughly reliable account of archaeological discoveries as they relate to the Bible. Editor: Edward F. Campbell, Jr., with the assistance of Floyd V. Filson in New Testament matters. Editorial correspendence should be sent to the editor at 800 West Belden Avenue, Chica- go 14, Illinois. Editorial Board: W. F. Albright, Johns Hopkins University; G. Ernest Wright, Harvard University; Frank M. Cross, Jr., Harvard University. Subscriptions: $2.00 per year, payable to Stechert-Hafner Service Agency, 31 East 10th Street, New York 3, New York. Associate members of the American Schools of Oriental Re- search receive the journal automatically. Ten or more subscriptions for group use, mailed and billed to the same address, $1.50 per year for each. Subscriptions run for the calendar year. In England: fifteen shillings per year, payable to B. H. Blackwell, Ltd., Broad Street, Oxford. Back Numbers: Available at 600 each, or $2.25 per volume, from the Stechert-Hafner Service Agency. No orders under $1.00 accepted. When ordering one issue only, please remit with order. The journal is indexed in Art Index, Index to Religious Periodical Literature, and at the end of every fifth volume of the journal itself. Second-class postage PAID at New Haven, Connecticut and additional offices. Copyright by American Schools of Oriental Research, 1964. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, BY TRANSCRIPT PRINTING COMPANY PETERBOROUGH, N. H. The Household Lamps of Palestine in Old Testament Times (First of a three-part series) ROBERTH ouSTON SrITH College of Wooster Although less impressive than monumental remains, lamps are among the most important artifacts of the ancient world. During their long history they underwent frequent changes of form, with the result that today they afford archaeologists a valuable chronological yardstick for the dating of other remains. They also constitute a rich mine for students of cultural dif- fusion, ceramic techniques, art, religious practices and, in some cases, sym- bolism. And to scholar and layman alike lamps impart, to an extent hardly matched by any other common ancient objects, an impression of the reality of life in times long past. Lamps are mentioned many times in the Bible, sometimes in contexts of considerable significance. The student of the Bible finds his attention drawn particularly to the ancient lamps of Palestine, since most of the biblical al- lusions to lamps arise from a Palestinian context. A century ago, when bib- lical archaeologyw as just coming into existence as a discipline, not even an outline of the history of these lamps could have been given, for objects had not yet begun to be excavated in such a way that they could be arranged sequentially and correlated with historical data. Today, having at our dis- posal a large amount of carefully excavated material, we can recover in con- siderable detail the history of Palestinian lamps throughout the biblical period. There are, to be sure, gaps in our knowledge, for some of the necessary evidence concerning rare specimens-particularly those of fine quality--is 1964, 1) THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST 3 lacking. We regret, for example, not having full information about metal lamps, for, as the ancients themselves knew, metallic forms sometimes in- fluenced ceramic ones (see Wisdom of Solomon 15:9). If we had a full repertory of metallic lamp forms we could undoubtedly explain puzzling features of certain terracottal amps. By working carefully, however, with the existing archaeological evidence we can fill in the picture reasonably well. The First Israelite Lamps From the time of the Hebrew settlement through the beginning of the divided monarchy, the per- ~??' iod commonly called Iron I, which spanned approximately the years 1200-900 B. C. - the dates are still the subject of lively debate - the only lamp in widespread use in Palestine was a simple wheelmade L'; one of the kind shown in Figure 2. Archaeologists, seeking a con- venient descriptive term, have var- iously called this a "shell lamp," "cocked hat lamp," and "saucer lamp." The ancient Hebrew, not needing to trouble himself with Fig. 2. Ifrroomn IT ellal mepn -Nofa scbae.h . 10Pthho tcoe nctouurryt esBy. Co.f, descriptive terms, called it by the tShceh loPoal loefs tiRneel igiIonns.t itute of the Pacific generic name ner (plural ner6th), a word meaning simply "lamp." This term ner comes from the root nyr (nwr), which probablyo riginally meant "to flame." Many extra-biblical texts more ancient than the Old Testa- ment use cognate terms in a way which reveals the background of the He- brew word. In the Ugaritic texts we find what appears to be a masculine noun n-y-r used in connection with the moon-god Yarikh (Nik. and Kath. 1.16, 2.3) and with the stars (Keret 2.1.37), and a feminine noun n-r-t used in a fixed (and probably very old) formula referring to the sun-goddess Shapash (Baal 2.8.21, Aqhat 1.4.49, etc.). Celestial associationsa re similarly attested in Accadian-Assyrian literature, where niiru is frequently used of gods such as Shamash (= Ugaritic Shapash), Marduk and Ninib, and nan- naru (from the same root) is used specially of the moon-goddess Sin, with the meaning "luminary, light-bearer." Aramaic texts from later times use cognate terms in a similar way, as does ancient Arabic tradition (e.g., the use of nfir in the Koran to refer to the moon, Sura 71.16). Celestial bodies 4 THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST (Vol. XXVII, were probably being called by the term ner or its various Semitic cognates long before lamps came into common household use; thus we do not find household terminology moving into cosmology but rather cosmology influ- encing household usage. Canaanite affinities were not limited to matters of terminology. The Hebrews did not invent the saucer lamp, but borrowed it largely unchanged from the Canaanites of the end of the Late Bronze Age, whose ancestors in Syria and Palestine had gradually been developing it since early in the 2nd millennium B.C. Contrary to widespread assumption, the lamp did not arise as an imitation of a shell. Bivalve shells may indeed have been used as lamps in some instances along the Mediterranean coast, as they apparently were upon occasion at Carthage in North Africa,1 and conch shells were made into lamps (and copied in stone and metal as well) in Mesopotamia as far back as the 3rd millennium B.C.;2 but these practices do not stand in the mainstream of lamp history. The saucer lamp actually developed from the ordinary household bowl, which itself had been used as a lamp during the Early Bronze Age. An interesting attempt to adapt the bowl-form to the spe- cific function of a lamp had been made during the centuries of disruption following the Early Bronze Age, when potters devised a flat-bottomed bowl with an undulating rim forming four equidistant spouts. When the chariot- warriorsa nd city-builders of the early 2nd millennium B.C. came upon the scene they did not perpetuate this design, but fashioned a simpler lamp by putting a single little spout on one side of a bowl. The development of the saucer lamp through the Middle and Late Bronze Ages consisted mainly of the evolution of the spout into an increasingly large and well-defined fea- ture of the lamp (see Fig. 1). By virtue of this Canaanite ancestry, Hebrew lamps had cousins in Cy- prus, north Africa, Egypt, Malta, Sardinia and elsewhere, even in parts of continental Europe-in short, wherever the Canaanite culture went over the centuries. During the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, specimens of Canaanite lamps had appeared only occasionally outside Syria-Palestine, but in the Iron Age they came into use to varying extents in these regions as a result of the energetic trade and colonization pursued by those latter-day Canaanites known as the Phoenicians. Even in areas where the Phoenicians were not actively colonizing, saucer lamps sometimes may have influenced local forms. The earliest household lamps of Greece, for example, appearing around 700 B.C., were saucer lamps not greatly unlike those of the Canaanites, even though they had some distinctly local features.3 1. M. Moore, Carthage of the Phoenicians, p. 32. 2. L. Woolley, Ur Excavations: The Royal Cemetery, p1s. 101a, 102a, 163, 182; cf. the bivalves and metal imitations used as cosmetic bowls, pl. 137c. 3. R. H. Howland, The Athenian Agora IV: Greek Lamps and Their Survivals, nos. 1-20. 1964, 1) THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST 5 Let us take a closer look at the Iron I saucer lamp of the Hebrews. Potters manufactured lamps as a part of their much larger repertoryo f cera- mic vessels. The craftsman first shaped a simple clay bowl and then folded its rim so as to form both a flange around the oil reservoir and a spout for the wick. This spout was probably called a museqeth. This noun, from the verb ysq, meaning "to pour, cast, flow," appears in connection with lamps only in Zech. 4:2, where until fairly recently it was mistranslated" pipe."4A lthough its attestation in the Old Testament is both late and scanty, it probably was used throughout the Iron Age to refer to a spout of almost any kind. The lamp-spout, was perhaps not originally devised as a wick-trough at all, but as a means by which the oil in the lamp could be poured back into a small- mouthed storage bottle without spilling; but it must at once have proved useful in holding the wick in position, for even the earliest Canaanite speci- mens of saucer lamp usually show by their carbon deposits that the wick was laid in the spout. The shape of the bowl and the folds of the wick-trough were deter- mined largely by common practice, potters ordinarily being careful imitators but reluctant innovators. The shape varied slightly from place to place and doubtless from potter to potter, as it necessarily does in a hand-crafted item, but throughout Palestine lamps of this period were fairly uniform in design. The most notable variation appears in the flange, which is usually fairly pronounced but sometimes, in a manner reminiscent of certain Late Bronze Age forms, is slight or even non-existent. Specimens were usually from five to six inches in length, though potters sometimes turned larger ones. As in any period, the kind of clay which was used varied with the locality, but throughout the Iron I period it tended everywhere in Palestine to be coarse with a sprinkling of limestone grits to give it strength. To judge from the speed with which Palestinian potters work today, an ancient potter was able to fashion a lamp in a few minutes, although the drying of the clay required many days and the firing and cooling of it several days more. An Iron I lamp was usually fired moderately hard to some drab shade of brown. While gen- erally pleasing in proportions, it seems to have been regarded by both its manufacturer and its user as a strictly utilitarian object, for it was almost never painted or otherwise decorated. In view of the simplicity of its pro- duction, a finished lamp probablys old for very little. Wicks were ordinarily made of flax, the usual term for which was pisheth; but in the two passages in the Old Testament where "wick"i s speci- fically intended, a less common term for flax, pishtah, from the same root, is used. The ancient Hebrews perhaps had no more specific term for "wick" 4. On the proper derivation and meaning of the term, see W. F. Albright, The Excavation of Tell Beit Mirsim II, p. 4. 6 THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST (Vol. XXVII, than this, though in later times the Aramaic word petilah, which literally means "twistedc ord,"b ecame a common designation for "wick."A wick could presumably be plaited from raw flax with little difficulty, but one could also be improvised from worn-out linen cloth or a number of other substances.5 Specially woven wicks may, of course, have been available for ceremonial purposes. As the carbon deposits on many lamps indicate, the wick was usually allowed to project slightly beyond the edge of the spout. The amount of this projection, along with the size and porosity of the wick, largely deter- mined the size of the flame. The ordinary saucer lamp was intended to hold only one wick, as its single spout indicates. When a householder wanted an especially bright light he could sprinkle some salt into the oil, apparently with the idea that it would clarify the flame. The Greek historian Herodotus noted in the 5th century B.C. that Egyptians fed their lamps on a mixture of oil and salt (History 2.62), and in the early centuries of the Christian era rabbis also knew the practice.6 We cannot be sure when the idea of salt as an additive first became known in Palestine, but it is not unreasonable to suppose that it dates back to the Iron Age. The function of the salt is not entirely clear. There is no doubt that burning sodium gives a bright yellow flame, but since salt is not soluble in oil it could not be drawn up into the flame. G. and C. Charles-Picard, who have performed some experiments with ancient lamps, say that a lamp's flame is brightened by the addition of a few grains of coarse salt directly to to the wick,7 but in my own experiments with ancient lamps I have been unable to get any satisfactoryr esults by this method. A much more effective way of obtaining a brighter light from a single- spouted lamp was the improvisation of a compound lamp by laying addi- tional wicks on the flange at the back of the lamp's oil reservoir.T his prac- tice was surely known in Iron I, though our earliest evidence consists of two Iron II specimens, one from 'Ain Shems and another from Tell en-Nasbeh,8 which show soot-blackening from six wicks laid at intervals along the flange, in addition to carbon on the spout. The householders may have been im- provising seven-spout cult lamps of the type which we shall soon discuss. Improvisations were not, of course, limited to adaptions of regular saucer lamps; sometimes an ordinary bowl was pressed into service as a lamp- probably most often in connection with burials, where there was sometimes a need for lamps on short order. 5. Cf. the list given many centuries later in the Mishnah, Shabbat, 2.1, 3 (all Talmudic citations are from the Babylonian Talmud). Numerous weeds and barks were usable. 6 Shabbat, 67b and the editorial notes in the Soncino translation of the tractate; also S. Kraus, T7 alGnm. uadnidsc hCe . ACrhcahraleeos-loPgiciea,r d, I, Dp.a il6y9 . Life in Ancient Carthage, p. 144. 8. E. Grant, Ain Shemis Excavations II, pl. XLV, no. 33; C. C. McCown, Tell en-Nasbeh 1, pl. 39, no. 16. 1964, 1) THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST 7 Many substances could be and were used as fuel for lamps,9 but the commonest of them was olive oil, extracted from the fruit by means of a series of beatings and pressings."0T he first extraction, obtained by beating the olives by hand, produced a light, relatively fat-free oil which was edible. The second and third extractions, obtained by crushing the olives in a press, produced oil of increasingly fatty content which was decreasingly edible. Consequently it was this oil of lower quality which was most often used in lamps, though only the best grade of oil was prescribedf or certain cult lamps (see Exod. 27:20, Lev. 24:2). Imported oils - sesame oil from Mesopotamia, castor oil from Egypt, or even more exotic substances-may occasionally have been used as lamp fuel," but it is unlikely that the ordinary householder could have afforded anything but local produce. It is impossible to determine by means of chemical analysis the kinds of oil used, since decomposition has almost always removed any residue of oil a specimen may have contained. A lamp of moderate size held enough oil for it to burn throughout the night if one desired, and since householders did not have the luxury of matches they had to keep a banked fire or a pilot light burning continuously. If analogies from other cultures are valid, we may assume that a woman was regarded as a poor housekeeper if she allowed her pilot flame to go out and had to borrow fire from a neighbor. It may be such a concept which under- lies the statement in the famous ode to a good wife in Proverbs 31:18, "Her lamp does not go out at night." Seeing that a pilot light stayed lit was not a task for a sluggard, for although a lamp would burn for several hours after being kindled, its wick would eventually burn down and require adjustment; the dutiful housewife would therefore probably have needed to arise two or three times during the course of the night to attend the lamp. This ever- burning flame did not, so far as one can discover, have any particular re- ligious significance;12y et what connotations popular piety gave to it we cannot say. The equipment for the maintenance of a lamp included several items besides the wick and the oil. Obviously a householder needed a storage con- tainer for the oil supply, but we cannot identify any particular form or size of vessel used for this purpose. He also needed a sharp-pointed instrument with which to adjust the position of the wick from time to time as the lamp burned. Numerous metal and bone objects which might have served such a 9. On the substances used in later centuries, see the Mishnah, Shabbat, 2.1-3 and Kraus, Talmu- dische Archaeologie, I, pp. 226f. Among the items which had probably been used for a very long time are animal fat and the sap of resinous trees. 10. See the Mishnah, Menahoth, 8.4f., which probably describes practices which were already centuries old; see further in Kraus, Talmudische Archaeologie, II, pp. 217ff. and J. M. Calderon, "Olive Oil," Encyclopedia Britannica (1960 ed.), XVI, p. 775. 11. K. Galling, Zeitschrift des Deutschen Paliistina-Vereins (ZDPV), XLVI (1923), pp. 32ff. 12. Ibid., where Galling discusses the matter at some length. 8 THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST (Vol. XXVII, function have been found in Palestine, but apparently none in clear associa- tion with lamps; in any case, such objects are far less numerous than lamps themselves, a situation which suggests that the householder frequently used nothing more than a sliver of wood as a wick-adjuster. Tweezers sometimes may have been used to extinguish a lamp's flame; apparently utensils of this sort, on a larger scale (i.e., tongs), are mentioned in connection with the tabernacle and temple lamps of the Yahweh cult under the name of mel- qdhayim or malqdhayim (see Exod. 25:38, 37:23; Num. 4:9; I Kings 7:49 [= II Chron. 4:21]; cf. Isa. 6:6), from the root lqh meaning "to take." Tweezers (and rarely tongs) have been found among excavated Palestinian artifacts, but never in close connection with lamps. Probably not to be in- cluded among the items of lamp maintenance is the knife-blade, since lamp wicks did not have to be kept trimmed in order to operate satisfactorily. Lamps were probably kept most of the time in concave niches in the walls of the house. House walls have rarely survived well enough for such niches to be preserved, but some Iron Age tombs contain them, as do some water tunnels.13 When the householder put a lamp on a table he probably placed beneath it a bowl, primarily for the purpose of guaranteeing stability to the round-bottomed vessel. Rabbinic literature of many centuries later speaks of this custom, but Iron Age evidence is largely lacking. One can compare, for what it is worth, the arrangemento f lamps and bowls in founda- tion deposits such as we discuss below. In Punic burials at Carthage saucers seem regularly to have accompanied lamps, but it is not clear whether these were always placed under the lamps. There is no close correlation of lamps and bowls in Palestinian interments, but the disorder in which most Iron Age tombs are found makes conclusions difficult. Iron I lamps are often poorly balanced, tending to tip backward when placed on a flat surface. The lamps cannot have been used in such a position; the lamp-maker seems to have supposed that the lamp would be placed in some kind of concave rest- ing place where balance was not required. On a table, a bowl would most easily meet this need. A bowl beneath the lamp would also have caught any oil which might slowly seep through the lamp, though a well-made specimen did not absorb and exude oil very rapidly. Some scholars have suggested that a lamp was soaked in water prior to each use, or even kept in a saucer filled with water, so that the water would fill the pores of the clay and prevent oil seepage. It is somewhat more likely that users poured a little water into a lamp before they poured in the oil; this would fill the pores of the clay and give the oil a surface upon which to float. W. M. F. Petrie draws attention to a passage 13. See, for example, W. F. Bade, Some Tombs of Tell en-Nasbeh, pp. 11, 16 (lamp-niches in a tomb), and J. B. Pritchard, Gibeon, p. 61 (lamp-niches in a tunnei). 1964, 1) THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST 9 in an Egyptian demotic text which speaks of one's putting gum-water or other substances into new lamps, presumably to fill the pores in some sort of per- manent fashion.14 The Talmud mentions saucers filled with water set be- neath lamps (Shabbat, 47b), but the passage may presuppose the special circumstances created by the use of naphtha as fuel in Mesopotamia in post-biblical times. It also speaks of one's putting a lump of clay under a lamp in order to make it burn more slowly (Shabbat, 67b); but an ord- inary saucer lamp with a moderate flame could not have become greatly heated, and in any case the clay could not have had much effect on the performance of the lamp. While speaking of the use of water in the operation of lamps, we may note an interesting lamp (Fig. 3) which has a built-in compart- ment below the oil reservoir. Using the neatly-made funnel which the potter has provided, the household- er presumably filled the compart- ment with water and thereby pre- Fig. 3. Lamp with lower compartment, late Iron I or Iron II period, from 'Ain vented oil from seeping from the Shems. (The cross-section is schematic rather than to exact scale.) Photo lamp's base. This ingenious kind of courtesy of Palestine Archaeological Museum, Jerusalem, Jordan. lamp did not come into regular use, perhaps in part because of the complexity of its construction. Lamps may sometimes have been placed on lampstands, but the use of such stands is not well-attested in the Iron Age. Bronze stands have been found, but never in direct associationw ith lamps. The Iron I lampstand may, as some scholars have assumed, have resembled a Late Bronze II tripod stand of bronze found at Megiddo along with a ceramic offering bowl.15 Ceramic lampstands are also not common in the Iron Age, those few which have been found probably had a cultic function. The specimen shown in Figure 4, with its pointed base which was designed specifically to fit the hollow stand, was found in an Iron Age tomb, where it had presumably been used in rites for the dead. Some saucer lamps with similar basal projects have 14. Petrie, Roman Ehnasya, p. 13. 15. For the stand and bowl, see H. G. May, Material Remains of the Megiddo Cult, pl. XVII, nos. M2702 and P3052. 10 THE BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGIST (Vol. XXVII, t~'I I' I, ' YI I1 /# vr LI Fig. 4. Lamp with ceramic stand, Iron I period, from el-Jib. From Animual of the Departlent of Antiquities, III (1956), fig. 20, no. 53, courtesy of Awni K. Dajani, Director of the Department of Antiquities. been found at Byblos in Syria. Similar in form, but larger and more elegant, are certain tall ceramic stands which have been found primarily in Canaanite contexts in Palestine.16 These lampstands were probably used chiefly in sanctuaries, as they were in the Bucheum (shrine of the bull god) in the 16. See, for example, Albright, Tell Beit Mirsim I, p1s. XLIV, no. 14 and L, no. 2.