The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution PDF

Preview The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution

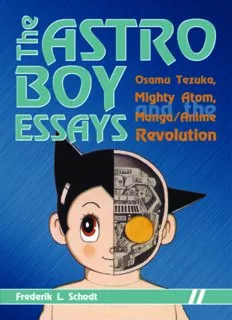

e ASTRO h T BOY ESSAYS e ASTRO h T BOY ESSAYS Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution Frederik L. Schodt Stone Bridge Press • Berkeley, California Published by Stone Bridge Press P.O. Box 8208 Berkeley, CA 94707 tel 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stonebridge.com All images were supplied by the author and are copyrighted by their respective rightsholders. Credits and copyright notices accompany their images throughout. Astro Boy images in the front matter and on chapter-opening pages are used by permission of Tezuka Productions. Front cover Astro Boy image is used by permission of Tezuka Productions. Text © 2007 Frederik L. Schodt. Cover and book design by Linda Ronan. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Schodt, Frederik L., 1950– The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga-anime revolution / Frederik L. Schodt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-933330-54-9 (pbk.) 1. Tezuka, Osamu, 1928–1989—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Comic books, strips, etc.—Japan—History and criticism. 3. Animated films—Japan—History and criticism. I. Title. NC1764.5.J32T4937 2007 741.5’952--dc22 2007017227 This book is dedicated to Osamu Tezuka (1928–89) Table of Contents Introduction vii 1 A National Icon 3 2 How “Mighty Atom” Came to Be 16 3 Designing a World 34 4 Mighty Atom, TV Star 55 5 Go, Go, GO Astro Boy!! 76 6 An Interface between Man and Robot 98 7 A Medley of Messages 119 8 A Complicated Relationship 145 Afterword 167 Appendix A: Japanese and English Manga Titles 177 Appendix B: Japanese and English Animation Episode Titles 185 Notes 197 Bibliography 204 Index 212 Introduction The death of Osamu Tezuka on February 9, 1989, at the age of sixty, sent shock waves throughout Japan, especially among those raised in the postwar period on his manga and anima- tion. Japan’s much beloved and aged Shôwa emperor had passed away the previous month, but the emotion surrounding Tezuka’s death seemed greater and resulted in an outpouring of not only grief, but endless media retrospectives and eulogies. On Febru- ary 10, the day after Tezuka’s death, Japan’s prestigious national newspaper, the Asahi, ran a prominent editorial titled “Mighty Atom’s Message,” urging younger artists to pick up the torch that Tezuka had dropped and to maintain the values symbolized by his most popular work. It noted that Japanese seemed to love comics far more than in other countries, and that foreigners often found this strange. After rhetorically asking why, it an- swered its own question: It is because in other countries they did not have Osamu Tezuka. The postwar comics and animation culture of vii viii • introduction Japan would never have happened without him. He was the creator of both story-based manga and television an- ime, and the influence of his attractive and androgynous boy character, Atom, with his long eyelashes, is easy to detect, not only in boys’ manga, but also in the protago- nists of the now oh-so-popular girls’ manga.1 For most of his life Osamu Tezuka was largely ignored outside of Japan. It is only recently, with the Godzilla-like glob- al rise of Japanese popular culture—and especially with the new overseas popularity of manga and anime—that his name has begun to slowly percolate into any sort of mainstream English consciousness. Tezuka’s animated TV series, Mighty Atom— known as Astro Boy outside of Japan—achieved considerable popularity in the mid-sixties in North America and temporarily opened the gates for other Japanese TV-animation series, but Tezuka himself received little exposure. In the late 1990s and at the beginning of the new millennium, some of Tezuka’s works began appearing in translation in English, but it is safe to say that most people outside of the manga-fan orbit have still never heard of them or of him, even today. There are, as of this writ- ing, no books in the English world specifically on Tezuka, yet in Japan there are scores of books on him. In fact, the Japanese re- gard Tezuka one of the greatest people of the twentieth century, up there along with John F. Kennedy, Mahatma Gandhi, and the Beatles, and he is sometimes compared in the media with Leonardo da Vinci. There are many reasons for this chasmic difference in perception, but the biggest is the high status com- ics and animation enjoy in Japan and the low status they have until recently had in North American culture. During his over-forty-year career, Tezuka created hun- dreds of stories and thousands of characters. Which raises the question: Why write a book focusing on Astro Boy/Mighty Atom and Tezuka, and not Tezuka and his entire canon? The answer introduction • ix to the first part is simple: Mighty Atom is Tezuka’s best-known work, and it is the work that helped create the framework for the modern Japanese manga and anime industries. The answer to the second part is more complex and involves both a con- fession and a digression to explain how I came to write this book. I did not grow up reading Mighty Atom manga or watch- ing Astro Boy animation, and only came to know Tezuka’s most famous work much later in life. I first went to Japan in the fall of 1965, at the age of fifteen. At that time, the first Mighty Atom television series was still being broadcast on the Fuji TV chan- nel, and while I did watch television, it was not a show that par- ticularly sticks in my memory. I could not yet understand Japa- nese, and it was a series designed for much younger children, so even if I had been a fan it would not have been very “cool” for me to admit it to my friends. But in addition to the TV series, I do recall seeing Mighty Atom–themed toys in stores, and espe- cially Atom masks at temple festivals, so I was very aware of the popularity of the character. My real exposure to Mighty Atom came much later in life, when I was old enough to admit enjoy- ing the stories and also old enough to appreciate what Tezuka had accomplished with them. In fact, I came to know Atom best after first knowing Tezuka’s other, more adult works and after knowing Tezuka himself. I began reading manga seriously around 1970, when I was attending a Japanese university in Tokyo and intensively study- ing the language. I lived in a dormitory my first year there, and I was astounded to see the huge weekly manga magazines that my roommates and other friends were reading (usually when they were supposed to be cracking their textbooks). At that time, manga were not the mass medium that they are today in Japan, but they had become a badge of pride for many university stu- dents, an important part of youth culture the way rock and roll