Table Of ContentQM

uirkinia

ec

& Si, Mo

tare

un

do

er G

(a

edrc

THE ARTS OF MAKING s)ía

,

IN ANCIENT EGYPT

This book provides an innovative analysis of the conditions of ancient

Egyptian craftsmanship in the light of the archaeology of production, lin-

T

guistic analysis, visual representation and ethnographic research. H

E

During the past decades, the “imaginative” figure of ancient Egyptian A

R

material producers has moved from “workers” to “artisans” and, most re- T

S

cently, to “artists”. In a search for a fuller understanding of the pragmatics

O

of material production in past societies, and moving away from a series of F

modern preconceptions, this volume aims to analyse the mechanisms of M

A

material production in Egypt during the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550

K

BC), to approach the profile of ancient Egyptian craftsmen through their I

N

THE ARTS OF MAKING

own words, images and artefacts, and to trace possible modes of circu- G

lation of ideas among craftsmen in material production. I

N

A

The studies in the volume address the mechanisms of ancient produc-

N IN ANCIENT EGYPT

tion in Middle Bronze Age Egypt, the circulation of ideas among crafts- C

I

men, and the profiles of the people involved, based on the material trac- E

N

es, including depictions and writings, the ancient craftsmen themselves T

left and produced. E VOICES, IMAGES, AND OBJECTS OF

G

Y MATERIAL PRODUCERS 2000–1550 BC

P

T

S

ISSBiNd 97e8-s9t0-o88n90e-5 2P3-0ress edited by

i

d Gianluca Miniaci,

ISBN: 978-90-8890-523-0

e Juan Carlos Moreno García,

s

t Stephen Quirke & Andréas Stauder

o

n

9 789088 905230 e

THE ARTS OF MAKING

IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Sidestone Press

THE ARTS OF MAKING

IN ANCIENT EGYPT

VOICES, IMAGES, AND OBJECTS OF

MATERIAL PRODUCERS 2000–1550 BC

edited by

Gianluca Miniaci,

Juan Carlos Moreno García,

Stephen Quirke & Andréas Stauder

© 2018 Individual authors

Published by Sidestone Press, Leiden

www.sidestone.com

Lay-out & cover design: Sidestone Press

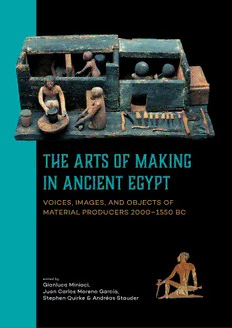

Photograph cover:

• Front cover: Wooden model ÆIN 1633 © Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek, courtesy of Tine Bagh

• Lower right: Detail of a manson at work from the tomb of Sobeknakht at el-Kab, Egypt

© Oxford University Elkab Expedition, courtesy of Vivian Davies

• On the back: Hippotamus in faience ÆIN 1588 © Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek,

courtesy of Tine Bagh

ISBN 978-90-8890-523-0 (softcover)

ISBN 978-90-8890-524-7 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-90-8890-525-4 (PDF e-book)

Contents

Introduction 7

Sculpture workshops: who, where and for whom? 11

Simon Connor

The Artistic Copying Network Around the Tomb of Pahery in 31

Elkab (EK3): a New Kingdom case study

Alisee Devillers

Antiquity Bound to Modernity. The significance of Egyptian 49

workers in modern archaeology in Egypt

Maximilian Georg

Epistemological Things! Mystical Things! Towards an ancient 67

Egyptian ontology

Amr El Hawary

Centralized and Local Production, Adaptation, and Imitation: 81

Twelfth Dynasty offering tables

Alexander Ilin-Tomich

To show and to designate: attitudes towards representing 101

craftsmanship and material culture in Middle Kingdom

elite tombs

Claus Jurman

Precious Things? The social construction of value in Egyptian 117

society, from production of objects to their use (mid 3rd –

mid 2nd millennium BC)

Christelle Mazé

Faience Craftsmanship in the Middle Kingdom. A market 139

paradox: inexpensive materials for prestige goods

Gianluca Miniaci

Leather Processing, Castor Oil, and Desert/Nubian Trade at the 159

Turn of the 3rd/2nd Millennium BC: some speculative thoughts on

Egyptian craftsmanship

Juan Carlos Moreno García

Languages of Artists: closed and open channels 175

Stephen Quirke

Craft Production in the Bronze Age. A comparative view from 197

South Asia

Shereen Ratnagar

The Egyptian Craftsman and the Modern Researcher: the 211

benefits of archeometrical analyses

Patricia Rigault and Caroline Thomas

The Representation of Materials, an Example of Circulations 225

of Formal Models among Workmen. An insight into the

New Kingdom practices

Karine Seigneau

Staging Restricted Knowledge: the sculptor Irtysen’s 239

self-presentation (ca. 2000 BC)

Andréas Stauder

The Nubian Mudbrick Vault. A Pharaonic building technique 273

in Nubian village dwellings of the early 20th Century

Lilli Zabrana

Introduction

Ancient Egypt is considered a true repository of beautiful objects. The fascination they

have exerted on Western imagery has certainly contributed to the consideration of

the land of the pharaohs as one of the cradles of Western civilization. Both ancient

Egypt and the Classical world (especially ancient Greece) were thought to share a com-

mon sense of beauty, harmony and delicacy that struck a chord with archaeologists

and visitors of museums all over Europe and North America. People capable of such

achievements were in some way “our” ancestors and paved the way to the sculptural

magnificence of a Phidias or a Praxiteles: ex oriente lux could not be better illustrated

than in the archaic and Egyptian-looking appearance of the archaic kouros.

However, here lie two problems, intimately related. One of them concerns identi-

ties, the other one work processes. Western culture has celebrated genius and freedom

of creation of their artists, an ascending path of progress contemporaneous to individ-

uality and market freedom in the realm of economy. The names of many artists, espe-

cially from the Renaissance on, occupy a place of choice in the pantheon of national

glories. Their fight to emancipate themselves from the constraints of patrons, conserva-

tive tastes and prudish social values are the best proof of the triumph of individuality in

modern times. Ancient Egypt, on the contrary, was catalogued as an “oriental” society.

Artistic creations depended on the commands of “despotic” monarchies that left little

room to the expression of geniality, a quality reserved to Western Artists. Under these

conditions, production was basically developed in workshops, a collective way of work-

ing that still reduced the possibilities of expressing individuality. If one adds the weight

of temples and “priests”, one was tempted to assimilate the conditions of Egyptian

artistic production more to the obscure European Middle Ages than to the heroic

times of a Phidias or a Michelangelo. The concept of “artisan” and “workshop”, and the

flavour of collectivism they carry with them, should explain why ancient Egypt, despite

its remarkable artistic achievements, was fatally doomed to fall short of producing

Great Art. Another continent was waiting for that.

At the same time, as the focus of research was put on beaux arts, workshops (spon-

sored by kings) and “artists”, ordinary craftsmanship has received less attention and its

analysis has depended on models elaborated elsewhere. One influential example has

been the idea of division of labour as concomitant to the birth of “complex” societies

and “civilizations”. According to this view, as economic activities became more com-

plex and the needs of people and, especially, nascent political powers increased, the

INTRODUCTION 7

emergence of full-time specialists was necessary. When their work was highly appreci-

ated (nature of raw materials involved, sophistication), such specialists were grouped

in palace or temple workshops and their produce commanded by and delivered to

these institutions. A perverse consequence is that this approach neglected the role of

rural and itinerant craftsmen/woman as well as that of people involved part-time in

agricultural activities and part-time in handicraft production. As for the very concept

of palatial and temple workshops, the archaeological evidence from Mesopotamia, for

instance, reveals that, contrary to this assumption, craft activities were usually dis-

persed in cities and hardly formed specialized urban areas. In other cases, alternative

circuits provided raw material used by rural craftsmen/woman. Mobile populations,

for instance, collected gold, especially alluvial gold, and it is quite possible that they

sold it not only to the agents of pharaoh but also to rural artisans. It has also been sug-

gested that people collected small blocks of stone from the quarries usually exploited

by the king and that they elaborated small objects. On the other hand, it is also well

known that temples adapted their production of certain items depending on the type

of consumers. In other cases, the imitation of high quality goods gave an impetus to

new types of objects adapted to a “low cost” demand, as it happened, for example, dur-

ing the Late Bronze Age. As for one of the most important craft activity of the ancient

world, the production of textiles, the very nature of the evidence preserved has focused

on institutional production, centred on palace and temple workshops. However, oth-

er documents reveal that small fleets of ships collected cloth from women and it is

quite possible that women played a crucial role as textile workers for merchants who

collected their production and sold it in Egypt and abroad. Nubians also emerge as

major vectors of the diffusion of leather cloths and specialized techniques of leather

preparation (dying, tanning) since, at least, the late 3rd millennium BC.

In this vein, craft activities appear as rather more complex activities than previ-

ously thought. The limits between “high” and “low” production, between qualified

specialists and part-time workers, between “artists” and mere “producers”, seem more

blurred, while the centrality ascribed to the production promoted at institutions such

as temples, palaces and the households of high officials appears questionable.

Pervasive preconceptions among researchers thus collide repeatedly and systemi-

cally with evidence for ancient patterns of and ideas around material production. All

fifteen contributors to this volume confront, in different ways, that continuing dis-

juncture. A shared focus on practice allows new thinking on the location and societal

value of different activities, and on their shifting social context of class, age, gender and

ethnicity, all inseparable from ancient categories and structures of thought in action.

Comparative archaeology and anthropology provide often the most promising

empirical and theoretical ground for avoiding assumptions in research. Here Shereen

Ratnagar (11) draws on South Asian archaeology to assess the times as well as places

of making, with “sporadic domestic activity” distinguished from regular production in

a socially transmitted technological line. Within Egyptology, Alexander Ilin-Tomich

(5) uses a single object-type, the stone offering-table, to take up the same question of

production timespace, with examples of centralised production set against evidence for

regional innovation. Rather than a dichotomy or a bland spectrum of possibilities, the

detailed evidence here delivers a more specific history of interplay in different output

locations. Similarly, assessing the category of “workshop” from the corpus of stone

8 THE ARTS OF MAKING IN ANCIENT EGYPT