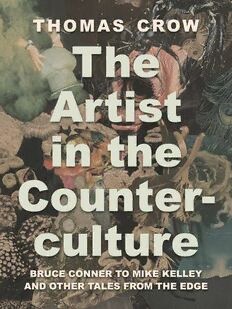

The Artist in the Counterculture: Bruce Conner to Mike Kelley and Other Tales from the Edge PDF

Preview The Artist in the Counterculture: Bruce Conner to Mike Kelley and Other Tales from the Edge

The Artist in the Counterculture The Artist in the Counterculture Bruce Conner to Mike Kelley and Other Tales from the Edge thomas crow Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2023 by Thomas Crow Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission. Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to [email protected] Published by Princeton University Press 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Jacket front Jean Conner, The Temptation of Saint Wallace (detail), 1963, collage, 50.8 × 38.1 cm, Collection San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase Jacket back Bruce Conner, hand-painted lightshow transparency, c. 1967, 5 × 5 cm, courtesy Conner Family Trust Page ii Bonnie Ora Sherk, Sitting Still (Golden Gate Bridge), 1971 Pages vi–vii “Artists Against Escalation” protest at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 16 May 1965, photograph by Charles Brittin, Charles Brittin Collection, Getty Research Library, Los Angeles Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Crow, Thomas E., 1948– author. Title: The artist in the counterculture : Bruce Conner to Mike Kelley and other tales from the edge / Thomas Crow. Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2022002244 (print) | LCCN 2022002245 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691236162 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780691236261 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Art and society—California—History—20th century. | Counterculture—California. Classification: LCC N72.S6 C76 2023 (print) | LCC N72.S6 (ebook) | DDC 701/.03—dc23/eng/20220709 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022002244 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022002245 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Designed by Gillian Malpass This book has been composed in Adelle and Adelle Sans Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in Italy 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Prologue Neuroplasticity 1 One Peyote Frontier 13 Two Movies and Mexico 35 Three Boston and the Leary Lure 49 Four Psychedelphic Oracle 69 Five Living up to Their Reputations 85 Six Bearing Witness to War 97 Seven From War Abroad to Oppression at Home 113 Eight Toward 1970: “The Ever-Deepening Spiral of Politics” 135 Nine The Art of Disappearance 149 Ten Noir Vortex 171 Eleven Secret Ceremonies 201 Twelve Last Artist of the Counterculture 225 Notes 250 Acknowledgments 266 Index 268 Illustration and Copyright Credits 278 1 Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Kunsthalle Bern, 1969), installation photograph, Harald Szeemann Papers. Photographs. Series IV.A. Projects, Getty Research Library, Los Angeles prologue neuroplasticity In the history of adventurously experimental art, the year 1969 is arguably marked by one event above all others. That year, the young curator Harald Szeemann, newly entrusted with the civic exhibition space in the city of Bern, sought to assemble evidence for a wave in art that he perceived but had escaped general recognition. To that end, he assembled works of sculpture by no less than sixty-nine artists from across Europe and both coasts of the United States.1 His inclusiveness extended to inviting a significant share of the participants to gather in the staid Swiss locale in order to install work on site and engage in protracted discussion, as far as the polyglot crew could manage, in a colloquy over the funda- mental character and function of art. The invited artists ranged from Joseph Beuys, the established master of the Düsseldorf Academy and advocate for art’s transformation into “social sculpture,” to the largely untried Keith Sonnier, raised in the Cajun backwoods of Louisiana, who was inspired to try out neon light as a medium for the first time and so discovered his career-long signature material. Other participants, like the Californian Bruce Nauman and the Italian Mario Merz, had gotten to tubular illumination before him, which proved one of a number of rhymes and resonances that knit the show into a unified visual statement, one that amply confirmed Szeemann’s intuition that some coherent tendency existed. Apart from scattered neon highlights and some shards of reflective glass, however, the overall look tended to a drab gray, ochre, and brown palette, the material textures rough and unrefined, their disposition sprawling and uncon- strained by any expected definition of formal integrity (fig. 1). Their curator attempted rationalizing the ensemble with this run-on list of attributes: “the obvious opposition to form; the high degree of personal and emotional engagement; the pro- nouncement that certain objects are art, although they have not previously been identified as such; the shift of interest away from the result towards the artistic process; the use of mun- dane materials; the interaction of work and material; Mother Earth as medium, workplace, the desert as concept.”2 Albeit disjointed, this list can stand for what has become the consensus view of this moment of “process” or “anti-form” in western art, down to the contemporaneous excursions into large-scale land art by Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria, and Robert Smith- son, who were all three represented in the show by cognate, gallery-scaled contributions. 2 Cover of the exhibtion catalogue for Harald Szeemann’s Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Kunsthalle Bern, 1969), collection of the author Indeed, Szeemann’s exhibition has retained landmark status for what seems to have been an uncannily moment-defining prescience. The only element that has failed to survive in received wisdom is the actual main title of the whole exercise: Live in Your Head. Those four words had been proffered by the young, long- haired Sonnier, to be happily adopted by Szeemann, who bannered them on the cover and title page of the catalogue (fig. 2). But in historical recollection, it is the latter’s subtitle, When Attitudes Become Form, that is invariably cited, sometimes along with the sub- subtitle, Works-Concepts-Processes-Situations-Information. Reasons suggest themselves as to why Sonnier’s pithy exhortation has effectively been erased in some collective act of willful 2 the artist in the counterculture