The Arab Americans: A History PDF

Preview The Arab Americans: A History

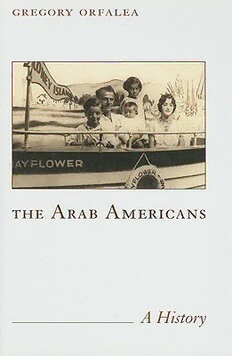

T A A he rab mericans A History GREGORY ORFALEA \ ! / OLIVE BRANCH PRESS An iuat)rirtf l)i Jnlc.dirti^W>Ushinj| trfoup, Inc. wwwrinterliHkbfKyks.com For Matthew, Andrew, and Luke— unending lone First published in 2006 by OLIVE BRANCH PRESS An imprint of Interlink Publishing Group, Inc. 46 Crosby Street, Northampton, Massachusetts 01060 www.interlinkbooks.com Text copyright T Gregory Orfalea, 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O r fa 1 e a, G re go r y, 1049- Tlie Arab Americans : a history / by Gregory Orfalea. p. cm. “Some of this book was published in 198<S, in different form, under the title Before the flames, by the University ofTexas Press”—T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56656-644-4 ISBN 1-56656-597-9 (pbk.) 1. Arab Americans—History. 2. Arab Americans—Social conditions. 3. Orfalea. Gregory, 1949—Travel—United States. 4. United States—Description and travel. 5. Arab Americans—Biography. I. Orfalea, Gregory, 1949- Before the flames. II.Title. E184.A650738 2005 305.8927073'09—dc22 2005002841 Eront cover photograph: Kamel and Matilda Awad, with their children, jrom left: Joe, Rose, and Eddie (infant) at Cooney Eland, XV, in the \H)s Bach cover photographs courtesy of Mel Rosenthal, from the exhibit “The Arab Americans”: left: Palestinian woman at a Brooklyn Heights peace march, September 16, 2001; right: Palestinian girl on rollerblades, Bay Ridge, Brooklyn 199H Printed and bound in the United States of America To request our complete 40-page full-color catalog, please call us toll free at 1-800-238-LINK, visit our website at www.interlinkbooks.com, or write to Interlink Publishing 46 Crosby Street, Northampton, MA 01060 e-mail: info(</;interlinkbooks.com CONTENTS Preface ini Introduction xiii 1. Generations Reunite in Arbeen, Syria 1 2. Seeds to the Wind: The First Wave of Arab Immigration (1878-1924) 43 The Stuff of Myth: Arab Adventurers in the New World • Ihe Withered Cedar: W hy the Arabs Left Syria and Dhanon • W ho Aw I? The Syrians Dock in America 3. Transplanting the Fig Tree: The First Generation on American Soil (1924-1947) 109 The Depression and Syrian Americans • World War II • Making a Xante: L'irst- CGeneration Xotables 4. The Palestine Debacle: The Second Wave of Arab Immigration (1948-1966) 151 Syrian Americans React to the Brewing Palestine Conflict • Immigrants from a Lost Palestine • Other Second Wave Immigrants from Arab Regimes 5. The Third Wave: West Bank Captured, Lebanon Torn Asunder, Iraq Wars with Iran, Kuwait, and the US (1967-2005) 189 Iraqis, Yemenis, and llgyptian Copts • 7 bird Wave Palestinians and Lebanese 6. The Political Awakening (1972-1981) 213 Ihe Association of Arab American University Graduates (A AUG) • The National Association of Arab Americans (XAAA) • "Ihe American-Arab Anti- Discrimination Committee (ADC) 7. Back to Lebanon (1982-1983) 243 Before the Plantes • The Israeli Invasion of Lebanon • All Pall Down 8. Stumbling Toward Peace (1984—2000) 265 Ihe Cases of Alex Odell and the LA 8 • The Coleico Doll and the Pirst Intifada Ihe Pirst Gulf War'Triggers Hate Crimes • Ihe Oslo Peace Process Access White House or Affirmative Action? • The Death of Oslo and the Second Intifada 9. After the Flames: Arab Americans and American Fear (2001-2005) 299 September / I and the Patriot Act • War with A fghanistan and Iraq Pront and Center • Wliat Do Arab Americans Want? Ongoing Achievement • To Be or Not to Be Arab American: A Dtok at the Literature 10. A Celebration of Community 347 Center of the World (Washington, DC) • Food Yon Can Trust (Detroit, MI) Dance oner the Death Home (Brooklyn, NY) • The Slave of Balfour House (Vicksburg, MS) • The Mosque and the Prairie (Ross, ND) A Porch in Pasadc}ia (Los Angeles, CA) Epilogue 434 Appendixes 436 /. Number of Arrivals in the United States from Turkey in Asia, by Sex, 1869-1898 2. Number of Arrivals from Syria in the United States by Sex, 1899—1932 3. Arab Immigration to the United States, 1948—1985 4. Arab Immigration to the United States, 1986-2003 .Arab Pastern Rite Christian, Muslim, and Druze Population in the United States 6. Religious Affiliations of Arab Americans Notes 444 Bibliography 463 Glossary 474 Index of Names 4 77 General Index 488 PREFACE once thought—hoped actually—I would never address this subject again. But history has a way of grabbing a writer—and a community—by the neck with challenges and trials no one could ever have imagined. Oh for the days when we were invisible! I have always had an instinct about danger—mysterious, but one that has been proved accurate enough times to make me take it seriously.The Arab-American community is in danger, from within and without. A few people hide among us who harbor hatreds that no one can fathom. At the same time, the society-at-large, fueled by decades of stereotyping of Arabs and by the atrocities of 9/11, seems prepared to pounce, should any more significant terrorism erupt on US soil. The vast majority of Arab Americans, who are a rather patriotic ethnic group at core, may pay worse than ever for the isolated newcomers limitless sense of wrong. Lest anyone think 1 exaggerate, consider that a member of the Bush-appointed US Civil Rights Commission during a 2002 hearing in Detroit predicted that Arab Americans would be rounded up in camps in the event of a newr terrorist attack. It was with this in mind that I returned to the history of my community, to reinterpret, reconsider, expand: to hold it up as talisman and warning. This history of Arab Americans is both more political and more literary than my early book (1988), in which political concerns were embedded almost imperceptively in the narrative. But the past two decades are the most political, by far, in the Arab-American community’s history, and a literary renaissance, if not naissance, is unfurling by the day. I now confront the growing spotlight on the community and weight on its shoulders, culminating in the horrifying events of September 11,2001, and the subsequent and troubling Patriot Act, which hovers over us still. Writing history while it is intensely in the making is a challenge, to say the least. Not a day went by when something on the front page (or further back) of the newspaper begged entrance to the new book. I had to be selective, of course, trying to divine what events and personalities best stand for the Arab-American saga. That story, once tangential to the wars of the Middle East, is, like the wars VII THE ARAB AMERICANS: A HISTORY themselves, front and center in our country’s fate. The earlier book did not have to face this extraordinary and perilous moment in history, on which the future not only of our country, but the world, may hang. The complex range of the Arab-American component to the post-9/11 world can be seen in these two surprising anomalies: there was an Arab-American fighter for bin Laden, and there is now an Arab American at the head of all US forces in Iraq (General John Abizaid). To further demonstrate the topsy-turvy changes in the community, in twenty years Iraqi Americans have gone from casting votes of virtually no weight here, to being voters whose votes are front page news—for candidates in Iraq! I note with sadness the prescience of the last line of the preface to the first book, which observed that “the fallout of America s Middle East policy draws ever closer to these shores.” Perhaps the United States was always at the center of gravity of this conflict and never knew it until now, if indeed we know it now. I suppose I sensed that the American-backed Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, which took close to 20,000 civilian lives and ended with spectacular massacres in Palestinian camps, was going to hurt us. How, I did not know and did not want to speculate. The terrorist attack on US Marines in Beirut in 1983, from which many have dated the downward spiral of fundamentalism in the area, seemed a stiff enough warning that we were not in tune with justice and there were people ready to use extreme, violent means to tell us so. No one could possibly anticipate the monstrosity of September 11. But I have to say I found myself nodding, grimly, at bin Ladens taped message on the eve of the November 2004 US presidential election, in which he speaks of first conceiving of an attack on the “towers of America... as I watched the destroyed towers in Lebanon” in 1982.1 It gave me a visceral shock to recall that, standing in the Beirut ruins of Fakhani, where an Israeli bombardment had taken out a six-story building, I had written, in the first book: “What would happen if the World Trade Center were hit this way in New York, or the Daily Planet building in Los Angeles? What would the world say? What would it do?”2 Well, the world said and did one thing; our democratically elected president did another. It goes without saying that nothing justifies the virulent hatred and destruction of the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, DC. But our Pontius Pilate hand-wringing concerning the effects of militant Zionism and Christian evangelism on the Holy Land has placed us in an untenable situation—we try to boost democracy in the very Arab world in which our client state makes a mockery of it, at least as far as the Palestinians are concerned.As the first President Bush noted, this cannot stand; either we fix the problem, which we have had a large hand in creating, or the fury of radical Islam will continue to haunt us. VIII PREl-ACE Fixing the Palestine-Israel problem, as 9/11 Commissioner John Lehman has suggested, is a sine qua non for snuffing the oxygen of Islamist terror, but not far behind is attention to the widening gap between the rich and the poor worldwide (it cannot help that half of all US foreign aid goes to two countries—Egypt and Israel); cancelling American aid to dictatorial regimes in the Middle East; and the moral imperative to help the Iraqis get back on their feet. With all due respect to our soldiers, our current military involvement appears more counterproductive on this account by the day Our very presence incites. As General Abizaid himself has said,3 getting the water, electricity, and roads in working order is a far more important task than the report of guns whose exercise gives us, at best, questionable returns. Political economist Hilton Root has put the trouble with US foreign policy even more succinctly: “humiliation.” The humiliation at the bottom of our policies that we have either refused or don’t care to see conies back to haunt us. I have tried to piece together suggestions from the Arab- American community about how we might extricate ourselves from the grim cul-de-sac our country finds itself in, and record as honestly as I could both the community’s disgust with terror as an approach to perceived injustice and its attempt to navigate as Americans in a decidedly paranoid atmosphere. This book is new. Even the earlier material about the history of the early Syrian immigration to and settlement in America has been cut, updated, and rewritten in parts with new research and interviews. Underpinning Hie Arab Americans are interviews I conducted with 140 Arab Americans spanning a period of a quarter century, including second interviews separated sometimes by many years. “The Political Awakening” (Chapter 6) has an interesting history in itself. The chapter looked at the major Arab-American organizations that grew into being after the 1967 war, and the University of Texas cut it entirely, saying it was “too political.” I restore much of it now as it offers an unusual glimpse of something not often discussed: how American Middle East policy is shaped on Capitol Hill. For a time, a weak but nascent Arab-American lobby battled it out with quirky foreign-policy aides who were bombarded at the same time by the Israel lobby. What struck me when I first blew dust off this lost chapter was how current the debate still is, for example, over settlements. The chapter gives an up-close look at the first (and last) time Congress tried to cut aid to Israel over the West Bank and Gaza settlements, through Senator Adlai Stevenson, who paid for his ill-fated effort with his career. Chapter 8, “Stumbling Toward Peace,” follows the roller-coaster ride the community took along with the Middle East in what appeared to be a peace breakthrough in Madrid and Oslo, then the IX THE ARAB AMERICANS! A HISTORY precipitous decline in that process after the assassination of Rabin, the hopelessly over-billed and over-rushed Camp David talks at the tail end of the Clinton era, and the rise of Ariel Sharon to power in Israel. Here, too, I look at the alarming spikes in hate crimes against Arab Americans and those who look like them during the 1991 Gulf war and after the Oklahoma City bombing. Stereotyping in the media, film, books, advertisements, and so forth, grew exponentially in this period and is responsible in part for the unleashing of a subliminal hatred or fear of the Arab in US society. To draw attention to “American fear” in the subtitle to Chapter 9 (“After the Flames”) may be misleading, because there is also a lot of American kindness after 9/11 that I have tried to represent. But the violent, at times Orwellian, backlash some in the community have had to endure is recorded, along with the strange tentacles of the Patriot Act. I look at the new demographic patterns and their implications. For example, the community, for a long time 90 percent Christian, is now about 75 percent Christian, 25 percent Muslim. The two community portraits in Chapter 10, Detroit and Washington, DC, are deeply concerned with 9/11 and how it has affected the community, from the singing of the Star Spangled Banner at the Comerica Park baseball stadium in Detroit by an Arab- American Muslim woman, to seven Arab Americans’ narration of “that black day” in the US capital. I do not hide my own. Even a few years before my first book was published, 1 had dropped out of political activism on behalf of the community. I have written elsewhere about this, but suffice to say here work in that vineyard is relentlessly punishing. It is shocking to the system and the heart to see how thoroughly Arab and Arab-American leaders can subvert, muscle out, and otherwise screw each other. The instincts of a “street fighter,” as one Arab-American leader described the requirement of success in American politics, I’m afraid I lacked. Though like Nikos Kazantzakis I tried to fuse the man of action with the man of contemplation, ultimately, like him, I ended up giving myself over to trying to understand as a writer what forms there were in the swirling dust and smoke, and where they were headed. Edward Said’s exemplary life as both brilliant literary critic and engaged revolutionary stands so tall to all of us who loved him, but even Edward, I think, would have admitted his own life ultimately stood with the power of the pen. This book is not about Middle East policy, per se; it does recount in several ways the Sisyphean attempt by one community to try and help, however much it has all seemed a crying in the wilderness. After the death of Arafat in 2005, there seemed hope that negotiations between Palestinians and Israeils would get back on track and that, wonder of wonders, Ariel Sharon might be preparing Israelis for a