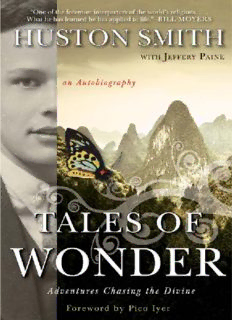

Tales of Wonder: Adventures Chasing the Divine, an Autobiography PDF

Preview Tales of Wonder: Adventures Chasing the Divine, an Autobiography

Tales of Wonder Adventures Chasing the Divine an autobiography (cid:1) (cid:1) (cid:1) huston smith with jeffery paine To Kendra “I asked so much of you in this brief lifetime, Perhaps we’ll meet again in the childhood of the next.” from a love poem by the Sixth Dalai Lama Tell me a story. In this century, and moment, of mania, Tell me a story. Make it a story of great distances, and starlight. The name of the story will be Time, But you must not pronounce its name. Tell me a story of deep delight. Robert Penn Warren Look at this, you scornful souls, and lose yourselves in wonder. For in your day I do such deeds that, if men were to tell you this Story, you would not believe it. St. Paul (speaking for God), Acts 12 Wonderful the Presence One sees in the present. Oh wonder-struck am I to see Wonder on wonder. the Adi Granth (the sacred book of Sikhism) CONTENTS Epigraph iii Foreword No Wasted Journeys by Pico Iyer vii Prologue Th e Explorer xi i i part i the horizontal dimension my life in historical time 1 Coming of Age in a Sacred Universe 3 2 An American Education 27 3 The Vocation Beneath the Career 41 4 Family: Th e Operetta 75 part ii the vertical dimension living in sacred time 5 My Soul of Chris tian ity 97 6 My Three Other Religions 113 7 Three Final Frontiers 153 Epilogue Reflections upon Turning Ninety 177 Appendix A Universal Grammar of Worldviews 189 Acknowledgments 197 Credits 199 Index 201 About the Authors Other Books by Huston Smith Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher FOREWORD No Wasted Journeys “be not simply good—be good for something,” henry David Thoreau wrote with typical force to a new friend, Harrison Blake, who had just approached him by letter. “To set about living a true life,” he had declared a few paragraphs earlier, “is to go [on] a journey to a distant country, gradually to find ourselves surrounded by new scenes and men.” Th oreau’s injunction was as much to the point as it was characteris- tic. Many people can share a certain light with us, the fruits of their explorations, and in that very transmission there is a special beauty and value; but the ones who really move us are sharing with us their lives, showing us how the principles they elucidate play out in the here and now. Aldous Huxley, lifelong experimenter, did not just write on the religions of the world; he tried, as far as possible, to live them. Th e Four- teenth Dalai Lama has not been merely a monk sitting in a remote kingdom, offering a model of clarity and goodness to his people; he has brought the values and ideas for which he speaks right into the heart of hard-core Realpolitik in Wash- ington and Beijing, into the urgency of trying to protect six million p eople under occupation, into the center of our mixed-up modern media circus. [ vii ] foreword Long before I had ever met Huston Smith, I felt drawn to this celebrated explorer of the great traditions because of my sense that he was not just teaching but living and acting. I went to hear him onstage and noticed how the lucidity and purity for which he spoke were also how he spoke; this was no mere scholar telling us what he read, but someone pass- ing on, with an infectious sweetness and integrity, what he had learned traveling to India, putting himself through the rigors of Zen practice in Japan, hitchhiking across the Amer- ican West to listen to Gerald Heard, becoming the one to re- cord Tibetan multiphonic chanting in the Himalayas. When I saw him speaking to Bill Moyers in a classic series of pub- lic-television interviews about the exploration of the Real and universal understanding, I realized these were far more than words; here was the rare professor who does yogic headstands, observes the Islamic rule, regularly reads scriptures from the eight major traditions—and goes to his local church (as well, of course, as seeing that even television can be a mass means to the useful end of disseminating ideas). A little later I was not surprised to learn that he had been a good friend of the Four- teenth Dalai Lama for more than forty years—acknowledged twice as a teacher by the Dalai Lama in his 2005 book on sci- ence; had been the one to introduce Aldous Huxley properly to Alan Watts; had, in fact, been not just a beloved profes- sor for half a century, who did as much as anyone to bring the world into the minds of Americans, but also a tireless ex- plorer who really did meet Eleanor Roosevelt and Martin Luther King and witnessed the founding of the United Na- tions and the uprising at Tiananmen Square. Th e first time I met him, I asked him if he had ever met Thomas Merton, and he told me the beautiful story, herein [ viii ] No Wasted Journeys alluded to, of how he found himself in Calcutta in 1968 and went out into a garden where a man was sitting with a soft drink, as if waiting for him. It just happened to be the man he most wanted to meet in all the world (and who would be dead, tragically, within a few weeks). Some would call this characteristic luck; to me it sounded like a kind of grace. Professor Smith has irreversibly changed and lightened and broadened the lives of millions of students and believ- ers (and, no less important, nonbelievers) through his clas- sic books, and those books have changed as the times have changed. He’s best remembered, no doubt, for the essential introduction to the world’s great traditions, The World’s Reli- gions, from 1964, which brought Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam into many American lives and households long before karma and nirvana were common terms; what distinguishes that work, even today, is how it sits inside every tradition that it describes, blending the rigorous eye of the scholarly out- sider with the beating heart of the initiate. Like a kind of Method scholar, the author seems to report on each tradi- tion from the inside out, as it might seem to one of its ad- herents, and in the process what he manages to do, without tendentiousness or strain, is to light up the places where reli- gions converge without ever denying the ineff aceable diff er- ences between them (and the danger of following a “salad bar” technique in which, by combining the elements of many faiths, one loses the depth of all). In later times, though, he has pushed this exploratory spirit further and deeper, defending religion against the reduc- tions of “scientism” (a task for which his fifteen years teach- ing at MIT well prepared him), fashioning, as Carl Gustav Jung might have done, a universal grammar of religion, even [ ix ]

Description: