Stories from the Clock Strikes Twelve PDF

1961·10.2893 MB·other

Most books are stored in the elastic cloud where traffic is expensive. For this reason, we have a limit on daily download.

Preview Stories from the Clock Strikes Twelve

Description:

Herbert

Russell Wakefield (1888-- 1964), bishop of Birmingham and one-time

private secretary to Lord Northcliffe, is most noted today for his ghost

stories. These stories were written in the tradition of M.R. James and

Algernon Blackwood. Critical response to Wakefield over the years has

been spotty but generally positive.

There are essentially three versions of H.R. Wakefield's _The Clock Strikes Twelve_. There was a first edition of 14 tales that was published in 1940. There was a later, expanded version of the collection published by Arkham House in 1946 that consisted of 18 stories. The third edition was an abridged version of the original, published by Ballantine in 1961 that consisted of a dozen tales.

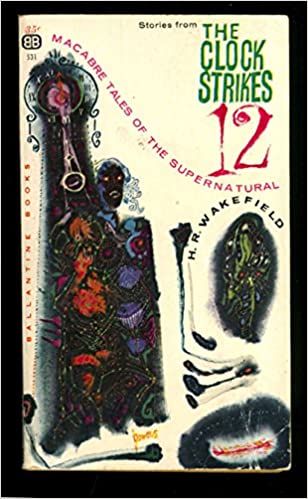

I am reviewing the Ballantine paperback edition of _The Clock Strikes Twelve_, one of Ballantine's Chamber of Horror series of paperbacks with spectacularly spooky-abstract covers by Richard Powers. The cover to this book shows against a white background, a slightly tilted, purple, demented grandfather clock with monster faces protruding from it and several sinister purple shapes floating alongside it.

Well, what kind of stories have we here? In a review of an earlier collection of ghost stories by Wakefield, M.R. James found that while the majority of the stories were ingenious, "I would remove one or two that leave a nasty taste" (479). In a similar vein, I found that three tales in this collection left an unpleasant taste in my mouth.

The stories are: "The Alley," in which an inoffensive man and his companions are slaughtered by spooks, leaving only their dog alive; "Lucky's Hill," in which Norse deities massacre a family for the heinous crime of chopping down a Christmas tree on the wrong hill; and "In Collaboration," the portrait of a madman who commits murder and comes to a rotten end.

The remaining nine stories strike me as being on the ingenious (if often downbeat) side of the fence. "Death of a Poacher" involves a hunter who runs afoul of some supernatural forces in South Africa. Its portrayal of an unusual kind of were-creature is both chilling and original. "Used Car" is about a fellow who buys a car for his daughter that turns out to be haunted by a pair of malicious ghosts who cause no end of mischief. "The First Sheaf" involves a conflict between Christianity and paganism in the English countryside. Paganism wins. I believe that several reviewers have noted a similarity between this tale and the later movie, _The Wicker Man_.

Two stories-- "'I Recognized the Voice'" and "Happy Ending?"-- involve telepathy or clairvoyance. John W. Campbell might refer to them as stories about "psionics". But I believe that Wakefield would cleave to more mystical definitions of the two phenomena. In the first tale, the point-of-view character recognizes a "bond" between him and another man. They meet. Tension cranks up between them until there is a final revelation. The second tale involves a young psychologist who is just a bit too scientific for his own good.

Two stories-- "In Outer Darkness" and "Final Performance"-- are smoothly told but fairly predictable pieces. The first is a haunted house story, and the second is a ventriloquist-and-his-dummy tale that used to be the rage with a number of writers Way Back When.

The last two stories-- "Jay Walkers" and "Ingredient X"-- strike me as more substantial pieces. The first involves some gruesome deaths on a stretch of road said to be "haunted". The truth turns out to be more complex. The second tale involves a man who rents a room that _looks_ attractive-- but which turns out to be a really nasty haunt. The last tale reminded me of the real-life room in the Reid House in Chattanoga, said to be haunted. (It was the site of an old murder.) Nobody has slept in that room for years. But on rare occasion, it is opened to the public for part of a "ghost tour".

Should writers of ghost stories believe in ghosts? Montague Summers (1931) was in no doubt that they must. H.P. Lovecraft (1945), on the other hand, held that materialists made _better_ writers of the supernatural, since they were less likely to take the atmosphere of their story for granted. In his introduction to the collection, Wakefield makes it clear that he is a believer in both ghosts and haunted houses and that he takes _frontier_ things like telepathy fairly seriously. Did these beliefs hurt his storytelling ability? I am inclined to think that they did not.

There are essentially three versions of H.R. Wakefield's _The Clock Strikes Twelve_. There was a first edition of 14 tales that was published in 1940. There was a later, expanded version of the collection published by Arkham House in 1946 that consisted of 18 stories. The third edition was an abridged version of the original, published by Ballantine in 1961 that consisted of a dozen tales.

I am reviewing the Ballantine paperback edition of _The Clock Strikes Twelve_, one of Ballantine's Chamber of Horror series of paperbacks with spectacularly spooky-abstract covers by Richard Powers. The cover to this book shows against a white background, a slightly tilted, purple, demented grandfather clock with monster faces protruding from it and several sinister purple shapes floating alongside it.

Well, what kind of stories have we here? In a review of an earlier collection of ghost stories by Wakefield, M.R. James found that while the majority of the stories were ingenious, "I would remove one or two that leave a nasty taste" (479). In a similar vein, I found that three tales in this collection left an unpleasant taste in my mouth.

The stories are: "The Alley," in which an inoffensive man and his companions are slaughtered by spooks, leaving only their dog alive; "Lucky's Hill," in which Norse deities massacre a family for the heinous crime of chopping down a Christmas tree on the wrong hill; and "In Collaboration," the portrait of a madman who commits murder and comes to a rotten end.

The remaining nine stories strike me as being on the ingenious (if often downbeat) side of the fence. "Death of a Poacher" involves a hunter who runs afoul of some supernatural forces in South Africa. Its portrayal of an unusual kind of were-creature is both chilling and original. "Used Car" is about a fellow who buys a car for his daughter that turns out to be haunted by a pair of malicious ghosts who cause no end of mischief. "The First Sheaf" involves a conflict between Christianity and paganism in the English countryside. Paganism wins. I believe that several reviewers have noted a similarity between this tale and the later movie, _The Wicker Man_.

Two stories-- "'I Recognized the Voice'" and "Happy Ending?"-- involve telepathy or clairvoyance. John W. Campbell might refer to them as stories about "psionics". But I believe that Wakefield would cleave to more mystical definitions of the two phenomena. In the first tale, the point-of-view character recognizes a "bond" between him and another man. They meet. Tension cranks up between them until there is a final revelation. The second tale involves a young psychologist who is just a bit too scientific for his own good.

Two stories-- "In Outer Darkness" and "Final Performance"-- are smoothly told but fairly predictable pieces. The first is a haunted house story, and the second is a ventriloquist-and-his-dummy tale that used to be the rage with a number of writers Way Back When.

The last two stories-- "Jay Walkers" and "Ingredient X"-- strike me as more substantial pieces. The first involves some gruesome deaths on a stretch of road said to be "haunted". The truth turns out to be more complex. The second tale involves a man who rents a room that _looks_ attractive-- but which turns out to be a really nasty haunt. The last tale reminded me of the real-life room in the Reid House in Chattanoga, said to be haunted. (It was the site of an old murder.) Nobody has slept in that room for years. But on rare occasion, it is opened to the public for part of a "ghost tour".

Should writers of ghost stories believe in ghosts? Montague Summers (1931) was in no doubt that they must. H.P. Lovecraft (1945), on the other hand, held that materialists made _better_ writers of the supernatural, since they were less likely to take the atmosphere of their story for granted. In his introduction to the collection, Wakefield makes it clear that he is a believer in both ghosts and haunted houses and that he takes _frontier_ things like telepathy fairly seriously. Did these beliefs hurt his storytelling ability? I am inclined to think that they did not.

See more

The list of books you might like

Most books are stored in the elastic cloud where traffic is expensive. For this reason, we have a limit on daily download.