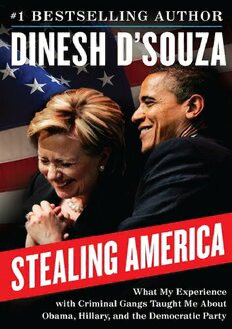

Stealing America; What My Experience with Criminal Gangs Taught Me about Obama, Hillary, and the Democratic Party PDF

Preview Stealing America; What My Experience with Criminal Gangs Taught Me about Obama, Hillary, and the Democratic Party

DEDICATION FOR DEBBIE FANCHER, Immigrant, patriot, and the woman I love CONTENTS Dedication A Note to the Reader Chapter 1 Crime and Punishment: How They Taught Me a Lesson Chapter 2 The World as It Is: Inside the Confinement Center Chapter 3 How to Steal a Country: A Heist to End All Heists Chapter 4 Creating New Wealth: America, the Anti-Theft Society Chapter 5 History for Profit: The Reparations Scam Chapter 6 The Things That Keep Progressives Awake at Night: The Greed and Inequality Scam Chapter 7 You Didn’t Build That: The Society-Did-It Scam Chapter 8 Silver Spoons and Genetic Lotteries: The Lucky Luciano Scam Chapter 9 The Godfather: Saul Alinsky’s Art of the Shakedown Chapter 10 Barack and Hillary: The Education of Two Con Artists Chapter 11 The Envy Triangle: Shaking Down the Wealth Creators Chapter 12 Cracking the Con: Restoring the Productive Society Acknowledgments Notes Index Photographs About the Author Also by Dinesh D’Souza Credits Copyright About the Publisher A NOTE TO THE READER The language spoken in a confinement center is extremely coarse. Hardly a sentence is uttered that does not contain obscenities. There is no way to convey the sense of place and even the meaning of what convicts are saying without using some of this language. Out of respect for the reader, I’ve scaled it way back and used asterisks to bowdlerize the most offensive words. Chapter 1 CRIME AND PUNISHMENT: How They Taught Me a Lesson If a man wishes to be sure of the road he’s traveling on, then he must close his eyes and travel in the dark.1 —John of the Cross, Dark Night of the Soul T he mood in the courtroom was tense and electric as I entered, accompanied by my superstar lawyer Benjamin Brafman and another attorney, Alex Spiro. We were in the Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse in lower Manhattan, the offices of Judge Richard Berman. Brafman, with his elegant locks of hair brushed back, looked completely at home in this environment. I, on the other hand, was not. I tried to look nonchalant, or at least expressionless. Inside, however, my heart was pounding with terror. In a very short time I’d know if I was headed to federal prison. My crime? I had exceeded the campaign finance laws by convincing two of my friends to contribute $10,000 apiece to a candidate for the U.S. Senate from New York; then I reimbursed them for their contribution. For this—I subsequently discovered—I could be prosecuted as a felon and sent away for up to two years. I had already pleaded guilty to the charge. Now I was going to find out whether the judge would give me a prison sentence. My greatest fear was not prison itself. At Brafman’s suggestion, I had hired a criminologist with extensive experience in the various federal prison camps. “If you get prison,” this fellow told me, “it’s going to be a white- collar camp, most likely Taft or Lompoc in California. You’re going to be surrounded by accountants, lawyers, dentists, bureaucrats. All the others in there have proven themselves through good behavior. These are nonviolent criminals, just like you.” That part—the “just like you”—jolted me. I almost didn’t hear the rest. “You’ll have to work part-time, but you’ll have lots of free time. There is little contact with the outside world. No cell phones and no laptops. But you can send emails from a general computer that is monitored, and you can make three hundred minutes of phone calls per month, also monitored. That’s not much, but you’ll get used to it. Taft, the camp I’d recommend for you, has pretty good facilities, a gym, a running track, a tennis court. You’re a writer, so do a lot of reading and writing. I’ll help to prepare you for what to expect. If you stay busy, and use common sense, you’ll be fine.” Fine? I took that as an exaggeration. Even if there was little danger of being stabbed or raped, how can someone who is locked up for two years, without a phone and a laptop, and such limited contact with the outside world, be fine? My deepest fears were over my nineteen-year-old daughter. She, I knew, would be devastated. I had recently gone through a difficult divorce and unfortunately my daughter’s relationship with her mother had been, at least temporarily, severed. Even though my daughter was now in college, in terms of immediate family, I was all she had. I was accompanied by a few close friends, and two sympathetic journalists, the seasoned veteran Jerome Corsi from WorldNetDaily, and a young reporter for Breitbart News, Adelle Nazarian. Nazarian said she was an immigrant from Iran and understood where I was coming from politically. Most of the crowd was hostile. The liberal press was there in force, from the staid New York Times to the rabid Daily News. The reporters are so young, I thought to myself, and how delighted they look at the prospect of me being sent away. These people hated me because I was a person of color who was also a conservative. They had regarded me as a race-traitor, an enemy of the people. Jonathan Capehart, a blogger for the Washington Post, opined that “Dinesh D’Souza is a disgusting man. . . . D’Souza should be in jail where he would no longer be able to assault the rest of us with his special brand of racist bile.”2 For guys like Capehart, I was about to get my comeuppance and they were about to get their schadenfreude. In the back of the room, I even had a critic from the evangelical right: I noticed the sly reporter from World magazine there to continue that publication’s long-standing vendetta against me. She avoided my gaze. Brafman told me the men walking around with badges were from the government’s prosecution unit. I noticed their smug expressions, anticipating victory, as if my incarceration were a foregone conclusion. There were also a few ordinary folk who had read about my case and came out of curiosity. My attention focused on the prosecutor, Carrie H. Cohen, a woman with an enduringly haggard and harassed expression, as if life has done her wrong. From two previous court hearings, I knew she was brash and abrasive. Carrie never shook my hand and she avoided eye contact with me; I got the impression she considered me, like all defendants, to be vermin. She also had an irritating habit of referring to herself as the Government. “The Government does not agree.” “Your honor, the Government will prove . . .” “The Government takes objection.” Meanwhile, I’m thinking, Who elected this woman? She reminded me of Inspector Javert from Les Misérables. Of course I kept these thoughts to myself. I asked Brafman’s associate Alex Spiro, “How important a case is this for her?” He said, “For Carrie? Oh, this is a career case. This could make or break her career.” Carrie, I realized, badly wanted me in prison so that her career could advance. I knew that Carrie was a stooge, an enforcer for people higher up than her. The most important people—her boss, an Asian-Indian federal prosecutor named Preet Bharara, and his boss, the attorney general Eric Holder—were not in the courtroom. Also absent was the biggest boss of them all, the president of the United States, Barack Obama. That trio, I knew, would all take a considerable interest in the outcome of my sentencing. My thoughts were interrupted by a loud voice in the courtroom. “United States versus Dinesh D’Souza.” What a phrase! I winced. “Please stand for Judge Berman.” The buzz quickly subsided. In sauntered Judge Berman, fully robed and looking solemn as usual, his head bobbing from side to side like an old family horse. Behind the judge came three of his clerks. Slowly, ceremoniously, the judge took his seat. The clerks planted themselves in chairs against the wall. Then began what I am going to call my official castigation.3 Normally sentencing is a perfunctory business, but not this day. The judge gave me a verbal flaying from the bench that lasted for the better part of an hour. During this time the clerks watched with evident bemusement; they seemed to enjoy watching their man carry out a ritual flogging. The judge insisted I had “willfully and knowingly” violated the law. He added, “Mr. D’Souza’s crime is serious.” One of the purposes of punishment, he suggested, is to discourage others from committing similar violations. “The public certainly needs to be deterred . . . from making phony contributions and violating the election laws.” I took this to mean I was going to be punished not just for what I did but also to send a message of discouragement to the general public.