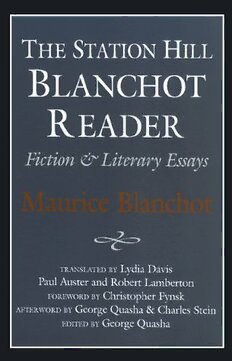

STATION HILL BLANCHOT READER PDF

Preview STATION HILL BLANCHOT READER

THE STATION HILL BLANCHOT READE is the only collection in English of Maurice Blancbot's mature fiction the unique genre he called recits (tellings, narratives)-as well as a selectio{l of literary/philosophical writings drawn from five of his major works. ft brings together seven ofB lanchet' s eight Station Hill books published ove;r the past twenty years: Vicious Circles, Thomas the Obsci~re. Death Sentence, The Madness of the Day, When The Time Comes, Tire One Who Was Standing Apa(l From Me, and ten of the eleven essays from The Gaze of Orpheus and Otho/' Literary Essays. The cumulative and multiple force of the literary works gathered in this co lection- ...a force, at times, that one associates with sacred texts or forms f mythopoicsis, a clarity, at other moments, that carries a sovereign humor t grips with the impossible ... - will reinforce, even multiply the strangends of each of the singular events of writing it presents. Christopher Fynsk, FROM THE FOREWOJ Of the small number of unimpeachably major, original voices in moder French literature, that of Maurice Blanchot has waited longest to find a audience in English. Station Hill is performing a great service by bringin I out Blanchot's enthralling fiction and essays. Susan Sontag cri~ Maurice Blanchet has produced an astonishing body of fiction and cism .... To enter [his] fiction is to enter a precarious world that asserts its freedom from the comfort and deadening habitualization of mimesis . . . .B eautifully translated. Gilbert Sorrentino, The New York Times Book Revidv Blanchot's prose gives an impression, like HenryJ ames'. ofc arrying mca~ ings so fragile they might crumble in transit ... [and] claims to contain somel thing wonderful, a treasure not so unlike, perhaps, the beekeeper's defia t courage in the face of pain. John Updike, The New York r Blanchot's power as a writer pierces, like a look that is too direct, the ind - terminate prose, and makes all relations, and especially our relation to tim , absolutely precarious. Geoffrey Hartman, The Georgia Revic 1 ISBN: 1-886449-17• 1 u11m 11n1 1 THE STATION HILL BLANCH OT READER • Fiction & Literary Essays Maurice Blanchot Lydia Davis TRANSLATED BY Paul Auster and Robert Lamberton Christopher Fynsk FOREWORD BY AFTERWORD BY George Quasha & Charles Stein George Quasha EDITED BY STATION HILL BARRYTOWN. LTD. CONTENTS This edition copyrighr © 1999 by Srarion Hill Press, fnc./Barryrown. Lrd. Copyrighr ©for the original French editions are held by Editions Gallimard, Edi A cknowledge111e11 ts Vl tions de Minuir and Editions Fara Morgana as listed on the Acknowledgements page. Foreword Copyright© 1999 by Christopher Fynsk List ef Translatio11s by Translator vu Afterword Copyright© 1999 by George Quasha and Charles Stein PUBLISHER'S PREFACE lX T r:mslacion copyright is held by the ttanslators in their original publications and© 1999 FOREWORD by Christopher Fynsk xv All rights reserved. No part oft his book may be reproduced or utilized in any form FICTION or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or FROM Vicious Circles: Two Fictions & "After the Fact" 3 by any infonnation storage and retrieval system, withom permission in writing from The Idyll 5 the publisher. The Last Word 35 Published under the Station Hill Arts imprint ofBarrytown. Lrd. in conjunction Thomas the Obscure 51 with Station Hill Press, fnc., Barrytown, New York 12507, as a project ofThe Death Sentence 129 Institute for Publishing Arcs, fnc., a nor-for-profit, federally tax exempt, educa The Madness of The Day 189 tional organization. When the Time Comes 201 Online catalogue and purchasing: http://www.stationhiU.org The One Who Was Standing Apart From Me 261 E-mail: [email protected] LITERARY ESSAYS 1:3ook design and typesetting by Chic Hasegawa with assistance from Susan Quasha The Gaze of Orpheus and Other Literary Essays FROM Cover design by Susan Quasha From Dread to Language 343. Grateful acknowledgement is due to the National Endowment for the Ans, a Fed Literature and the Right to Death 359 eral agency in Washington, DC, and to the New York Stare Council on the Arts for The Essential Solitude 401 · partial financial support of the publishing program ofThe Institute for Publishing Two Versions of the Imaginary 417 Arts and oft he individual books in this collection in their original Station Hill Press publication, as well as supporcofsome oft he translations. Reading 429 The Gaze of Orpheus 437 Library ofC ongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Song of the Sirens 443 . l:31anchor, Maurice. The Power and the Glory 451 [Selections. English. 1998] The Narrative Voice 459 • The Station Hill Blanchot reader: fiction & literary essays/ by Maurice Blanchor; edited by George Quasha; translated by Lydia Davis, Paul Auster, The Absence of the Book 471 &by R Goeboerrgte L Qamuabsehrato &n ;C Fhoarerlweso Srdte biny .C hristopher Fynsk; publisher's afterword FROM Vicious Circles: Two Fictions & "After the Fact" p. cm. After the Fact 487 ISBN 1-886449-17-1 Translators' otes 497 I. Quasha, George. II. Davis, Lydia. HI. Auster, Paul, Lamberton, Robert. V. Title. 1947-. IV. A f-TER WORD: P11blisl1i11.~ Bla11choc ;,, A 111erica-A Metapoetic View 509 PQ2603.L3343A6 1998 by George Q11asha a11d Charles Scei11 843'.912-dc21 Biographical Notes 528 <l 9 :t. n o 5 fl Other Bocks i11 English by Ma11rice Bla11cl1ot 529 LIST OF TRANSLATIONS A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS BY TRANSLATOR Graceful acknowledgement is due co the following publishers for the right co translate and publish works of Maurice 8lanchot in English: Paul Auster EDITIONS GALLIMARD Thomas /'obswr, copyright© 1941 by Editions Gallimard. Vicious Circles: Two Fictions & "After the Fact" L'Arrer de mort, copyright© 1948 by Editions Gallimard. IDYLL A11 momem rxm/11, copyright© 1951 by Editions Gallimard. LAST WORD Ce/11i q11i ne m 'accompagnait pas, copyright© 1953 by Editions Gallimard. After the Fact The translations of the essays from The Gaze of Orpheus arc based on the French editions copyright © 1943, 1949, 1955, 1959, 1969 by Edi Robert Lamberton tions Gallimard, as follows: Thomas The Obscure "De 1' Angoisse au langage" fromFa11x Pas (1943); "Litterature et le droic a la more" from La Part du jeu (1949); "La Solitude essentielle," "Le Lydia Davis Regard d'Orphee," "Lire," and "Les Deux Versions de l'imaginaire" Deat h Sentence from L'Espace litteraire (1955); "Le Chant des Sirenes" and "La Puis The Madness of The Day a sance et la gloire" from Le Livre venir (1959); "La Voix narrative" When the Time Comes and "L'Absence du livre" from L'Entretien infi11i (1969). The One Who Was Standing Apart From Me EDITIONS DE MINUIT Le Ressassement heme/, copyright © 1951 and as Apres co11p © 1983 by FROM The Gaze of Orpheus and Other Literary Essays: Editions de Minuit. "From Dread to Language" EDITIONS FATA M ORGANA "Literature and the Right to Death" La Folie du jo11r, copyright© 1973 by Editions Fata Morgana. "The Essential Solitude" Copyright for the English translations is as follows: "Two Versions of the Imaginary" Tl1omas the Obsc11re copyright© 1973, 1988, 1999 by Robert Lamberton, "Reading" 1 published by arrangement with David Lewis, Inc. "The Gaze of Orpheus" Vicious Circle: Two Fictions & ''After the Fact," copyright© 1985, 1999 by "The Song of the Sirens" Paul Auster. "The Power and the Glory" Death Sentence, copyright© 1978, 1998, 1999 by Lydia Davis. "The Narrative Voice" The Madness of the Day, copyright© 1981, 1999 by Lydia Davis. "The Absence of the Hook" Wl1en the Time Comes, copyright© 1985, 1999 by Lydia Davis. The One Who Was Standing Apart From Me, copyright © 1993, 1999 by Lydia Davis. The Gaze of Orphe11s and Other Literary Essays, copyright© 1981, 1999 by Lydia Davis. Quotations from Hegel arc from A.V. Miller's translation, Plie110111c11ologyofSpiri1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977). PUBLISHER'S PREFACE The Station Hill Blanchot Reader comprises most of the books by Maurice Blanchet chat Station Hill has published, and for us it is an appropriate way of celebrating two decades of publishing. Death Sen tence (1978) was, after all, the Press's first fulJ-length book. This fact underscores the great significance Blanchet has had for us in the devel opment of ourpublishingptogram, alJ the more so in light of the present colJection. Editing this edition has given us the opportunicy to reread and rethink an astonishing body of work. We have always expected that, among the hundreds of books published, a certain number would remain fresh; but we were frankly unprepared for how much the whole ofl:3lanchot's work continuously reinvents itselfa ccording co one's own capacicy for "further reading"-reading "beyond oneself" By the 111/iole of his work we of course mean not only the books published at Station Hill, but also the impressive number of his books to come into English very soon after the first three-that is, after 1981. These three--Death Sentetue, The Madness of the Day, and The Gaze of Orpheus and Other Literary Essays-were the first books of Blanchet in English to go into full trade distribution. Of these, the first cwo, along with Vicious Circles: TuJO Fictions and "After the Fact" (1985), When the Time Comes (1985), Thomas the Obsc11re (1988), and The One Who Was Standing Apart from 1 Me (1993), are fiction, essentially what Blanchet has called recits (trans latable variously as tale, telling, narrative, story, even recital, but in any case distinguished from novel).2 Thus most of the present book is in fact literary fiction, comprising most of the works Blanchet directly characterized as recits. The Gaze of Orpheus, most of which is reprinted here, is entirely non-fiction, what, for convenience, we have called Ii terary essays. The two sections of this book, Fiction and Literary Essays, are arranged chronologically accord ing to date of first publication; the exception is the "two fictions" of Vicious Circles, written in his 1935-36, so placed at the beginning here (discussed by Blanchot in his 1983 essay, "After the Fact," the latest text in the present book, placed at the end).3 Also somewhat excep tional is The Madness of the Day, generally read in the 1973 version in cluded here (Editions Fata Morgana), but arranged now according to the date of its 1949 magazine publication under the title, "Un recit?" IX THE STATION HILL BLANCHOT READER PUULISI !ER'S PREFACE Each piece in the book, fiction and non-fiction alike, stands alone as friends- has been for twenty years the background support oft he project a literary work.~ The Station Hill Blanchot Reader is not a "thesis" book of publishing him. . In the same spirit we feel indebted to the three remarkable vvnter/ except in our saying that these works deserve to be read each in its own translators to whom our opportunity here to read Blanchet in English right and as the literary instance of itself-each for its own particular power. Such reading--rcading that stays, as it were, in the open, remain literally owes everything: Lydia Davis, Robert Lamberton, Paul Auster. ing unencumbered by interpretation or contextualization- protects the In addition to graciously carrying out the notoriously hard work oft rans free "space ofliterature" (in Blanchot's phrase) necessary for this work lating Blanchet-with celebrated brilliant results-they have always been to be what it really is-work so tmly itself that it goes beyond itself. There supportive of each other's work and of the difficulties of independent are many genuine ways of reading and interpreting Blanchot and the publishing. . questions raised by his thought-deconstructive, historical/political, and Thanks are due to P. Adams Sitney for urging us in 1977 to publish so forth, and indeed a number of excellent discussions are now avail Hlanchot, for editing The Gaze Orpheus and Other Literary Essays and for able. But to enter a work by Blanchot armed from the start with a reading and helping revise the translations therein. On that book, Rob 5 critical perspective violates the free and inquiring nature of his self ert Lamberton generously served as translation text editor, "the book's revolutional text. The text is first of all a mystery. It wants to be read essential critic" according to Lydia Davis. Paul Auster offered consulta pure and simple-for which one can receive no wiser counsel than tion, and Michael Coffey brought his copyediting and proofreading skills Blanchot's own essay "Reading." to the type in chat book. At the same time, it is the right of (maybe even a necessity for) any Publishing at Station Hill has always been collaborative, as has edit- true reader ofBlanchot to develop a working "theory of reading" the ing our series ofbooks by Maurice Blanchet." Many hands have touched text. Certainly we have come to read him in a somewhat special way, these books in their making-too many to acknowledge more than a which we sometimes think of as a poet's way, by way of poetics and, few individually: Patricia Nedds bravely printed the first few Blanchet most especially, of metapoetics, the self-transformative. We mention this cities in our Open Studio Print Shop-at the beginning, when we here to signal again Blanchot's importance for us in the context of Sta thought that we had to do everything ourselves. Susan Quasha, co tion Hill's history and development, and also co point to our own state publisher from the beginning, co-designed most of the books. For the ment laying out a meta poetic view-of the axial and the liminal-which present collection, Chic Hasegawa did the typesetting; Merabi Uridia we have confined to an Afterword, "Publishing Blanchet in America." and Siu Yuen contributed to our collective proofreading of the book. We have no wish to put our own view before the work itself The force Charles Stein has been my partner in every aspect of bringing this of Blanchot's text in fact may be, to a truly extraordinary degree, its project to fruition, and of course he is co-author of the Afterword. To power to generate readings, the plural voice in one's head that alone thank a true dialogical companion is curiously confusing, risking sepa gives reading an ontological role like none other. ration in what is held in common. We arc very grateful for Christopher Fynsk's Foreword which so There have been many grants of financial assistance along the way spaciously prepares the ground for what follows. Like his own umg11age that made che preeminently non-commercial project of publishing and Relation: ... that there is language, it puts us in a mind of realizing the Blanchet in America possible for a non-institutional, non-endowed, barely audible urgency ofBlanchoc's invitation to read. We are person independent literary publisher. Some of Lydia Davis' translations re ally graceful for Christopher Fynsk's support and gentle guidance in the ceived special translation grants from the New York State Council on preparation of this book. the Arts. Her many months of work on The Gaze <if Orpheus were funded To thank Maurice Blanchet at this point strains the performacivc under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of the De value of words, yet the impulse is too strong co ignore. His generosity partment of Labor-certainly an unusual event in the history of public perhaps the quality most frequently mentioned among his translators and funding. The production of ::ill of the individual books was in some x XI THE STATION HILL BLANCHOT READER l'UOLISHER'S PREFACE measure funded by grants from the New York State Council on the 1 First published in 3 small hardback edition by David Lewis, Inc. in 1973. Arts and the National Endowment for the Arcs. Our deeply felt 1 The defining instance i~ T110111as tire Obsmre, the first version ofw hich Blanchoc called a acknowle?gcment goes to the adminjstrators and panelists who have roman, the reduced (by ~VO-thirds) ve~ion a rkit-an ope11i11gofficcional form by retl11nio11. stood ~ehmd ~son these projeccs. May the radiant presence ofBlanchot's Blanchot says the r&ir "is not the narration ofa n event. but that event it.~elf, the approach work m En.ghsh be received as a credit to the responsible people and co chat event, the place where that event is made to happen''-narrative as perfon11a1ivc, the responsive process behind public arts funding. moving. as it were. toward the condition of poetry. (Sec "The Song of the Sirens.") Written in 1935-36, contemporaneously with the first version of Thomas tire Obs<un> George Q11asha ( 1932-1940), the ··~vo fictions" of Vicious Circles may seem problematic in relation to the Barrycown, New York distinction mit, which is the word u~cd for them in "After the Fact" (though the distinc tion is noc emphasized in our translation). ' Note chat while the categoric~ fiction and non-fiction/essays break down quite thor oughly as Blanchot's work develops, none of the problemacic later works, significantly liminal co the two domains, is presented here. •The one Station Hill Blanc hot book not represented here is Tire U11a1101vable Co111m1111ity (1988). While immensely important as an inquiry into community and as a contribution co Blanchoc's works in which chinking integrates historical/political/social/philosophical focus, ic does not stand alone co che degree that the ochers included here do. Optimally ic would be read in dialogue with the works it discusses ofGeol"boes Bataille,Jean-Luc Nancy and Marguerite Duras. 5 For instance, Michael Holland's excellent collection, The Blan<hot Reader (Blackwell Publisher!"., Led.: Oxford, 1995) . seeks "to situate its author squarely in his time." He aims, adm.irably. co correct an imbalance in Blanchoc reading chat makes it appear "as if[the writing) cook place out~ide time and cook no account of history." This view, however, should stand in a dialogical relation with others, including the ocher end of the temporal spectrum-the infinite, from which. accord.ing co Blanchot, all must also be viewed. 6 The designation '·editor" of chis Reader is not meant to overshadow the roles of the others mentioned here. some ofw hom gave enormously oft heir time and energy. Perhaps being ecliror means little more, in chi~ case, than feeling responsible, during ~vo decades. for whatever could or did go wrong. The translators oft he fiction decided for themselves what they would translate. Sitney chose the essays for Tire Gaze ofO rpheus. For my part, I have always felt more instructed than instructing, especially by che agonizing/exhilarat ing "editorial" reading ofa translation ab>ainsc Blanchot's original (most memorably. Tire 011e Wlro Was Sta11di11J? Apart from Me), or the process of"inventing" Blanchoc's tides in English. The latter coo was collaborative--illum.inatingly. Scaring at our list ofd ozens of possible rranslarions of"L e Rcssasscmeut Ctemel," Michael Coffey and I flashed on "Vicious Circles" at virtually the same instant. (Blanchot. happily, expressed pleasure in the discov ery.) Robert Kelly ended che impasse of another long list for '~u Moment vo11/11" "vich "When the Time Comes." xii xiii FOREWORD To begin to define Maurice Blanchot's place in modern French let ters, one must consider, in addition to the literary works, a newly avail able body ofj ournalism and a vast range of literary and philosophical meditations published over a period of sixty years-writings with an extensive, but often indirect influence. One must consider the impor tance of the friendships with Georges Bacaille and Emmanuel Levinas, among ochers, and take into account the effects of his complex partici pation in French public life (an always active participation, even in times of withdrawal). The critical task is daunting, and it grows daily as the lineaments ofBlanchot's activities are drawn into the historian's light. But however many elements are gathered for the dossier, an appre ciation of Blanchot's insistence in modern letters requires attention to the strange force of his language. Indissociable from the fascinating power of any Blanchotian theme or critical motif (the author's Orphic quest, for example, or the death that is the impossibility ofd ying) is the haunting presence of a language that brings language itself into question as it searches the borders of what can be said in its time. This language offers itself everywhere in Blanchot's text. But when it is heard from the multiple space of resonance created by Blanchot's own literary re search-a series of singularly arresting textual events-one can begin to appreciate the sway of Blanchot's presence in texts as marking for our epoch as those ofJ acques Derrida, Michel Foucault or Jacques Lacan. Only from the ground of such a relation to his language, in fact, can we properly appreciate Blanchot's importance for a generation of French poets, for the literary and cinematographic works of a Marguerite Ouras, or, to leave the French context (as Blanchot's renown did long ago), the thought of Hajime Tanabe, the literary criticism and theory of Paul de Man, or the contemporary video art of Gary Hill. We can begin then to understand how Jacques Derrida could ascribe to one of the voices in his "Pas" the assertion that Blanchet remains far ahead of us: "Waiting for us, still to come, to be read, to be reread by those who have done so ever since they have known how to read, and thanks to him."1 I believe it is fair to say that Station Hill Press- initially, and still to this day in part, an artistic project- began from an assumption like the xv THE STATION HILL BLANCHOT READER FOREWORD one I have offered concerning the place ofBlanchot's literary language ends with a veritable ducat co the reader), and an ostensive silence re when it undertook co sponsor, in conjunction with a critical collection garding what has brought them forth or what they are (not) saying. In edited by P. Adams Sitney (Tlze Gaze of Orplze11s), a series of admirable brief: Blanchot's literary writings have commanded a cautious respect literary translations by Robert Lamberton (Tlzomas the Obscure), Lydia chat seems almost unmatched in modem criticism; the works have been Davis (Death Sentence, The Madness of the Day, When the Time Comes, left alone. and The One Who Was Standing Apart from Me), and Paul Auster (Vicious Does the present collection transgress in departing from this reserve? Circles). The importance of chis initiative cannot be overestimated for Certainly-but perhaps not in a regrettable way. For while it is not che reception of.Blanchoc in the English-speaking world. For while che easy co imagine these texts under the same cover, there is no basis for latter reception has been somewhat isolated (a representation of post supposing that their proximity in a single volume will mute their po war literature that takes its stare from Sartre has dominated the Ameri tential as singular events and efface their solitude. le could well serve, can academy), it has been intense-shaped in an essential way by the on the contrary, to underscore the distances that open between chem fact that English-speaking readers have been able to approach Blanchot's by virtue of the literary movements they share: their "common" en critical and theoretical writings from the basis of an engagement with gagement of the interruptions proper to what Blanchot sometimes names works of the order of Thomas the Obswre and Death Sentence. Thus, the a "speech," sometimes "saying," and, increasingly in his later work, publication of a collection of Station Hill's translations is not an indif "writing." It could help co draw forth from each of the works (from ferent event, and the question immediately arises: Will the present col their resonance, their interrupted rhythms, their folds) their exposure lection, enabled by the growing recognition of.Blanchoc's place in mod of an "infinite" in language that both divides and relates them in their em French thought, renew in some way Station Hill's contribution to differences from one another and from themselves. Blanchot would t~e .reception ofB~anchot? What might we expect from chis new pub call the field of this exposure a "relation without relation"; borrowing lishing venture, chis partial summary of Station Hill's past efforts? Will from BacailJe, he would call it a "communication" (without common this remarkable compilation oflicerary, critical and "speculative" works terms). If such a communication is furthered by this collection, it will by Blanchot serve the futurity co which Derrida has referred? reinforce not only the solitude of the textS, but also the questions that In these prefatory words, I would like co suggest why it may indeed speak in chem, questions whose philosophical, political and ethical im answer co that futurity by helping co change the very manner of reading port is in no way limited by the opacity of their origin. Blanchot in the English-speaking world. My hope, at least, is chat its My hypothesis, in other words, is that the alignment of texts will juxtapositions-startling, perhaps even unnerving for some who have help to bring forth in each of them, and between chem, a trace of the lived with the individual volumes-will invite readers to entertain the "research" to which they belong, namely Blanchoc's unending, mul relations between the works presented, and then prompt chem co con tiple engagement with what he terms the question of literature. This sider their disruptive relations to a multiple set of histories: literary, volume will do more than make Blanchot's work more easily available philosophical, political and biographical. Commentators have not failed or represent a significant portion of his literary accomplishments. In to evoke such relations, but most have found it difficult to make seeps fact, it will do something quite different from what is traditionally ex between the fictional works, or between those works and their histori pected of a "collection"; it will reinforce. even multiply the strange cal sices.2 This is in pare because works like Deatlz Sentence and Tlie ness ofe ach oft he singular events ofw riting it presents, drawing forth in Madness of the Day actively inhibit such steps. Their formal coherence this way the question of what is at stake in che fact that such texts (if it may be called chat) defies any extant critical categories, while their exist-a question that cannot but lead far beyond the name "Blanchoc." language, ~0th.limpid and strange, turns aside constantly from the "day" The last question appears in a "Note" to The Infinite Conversation of referenc1al. nes. To these grounds of a forbidding solitude we muse that develops it in a way that is pertinent to what I would like to suggest add an occasionally overt defiance {the first version of Death Sentence xvi XVII TH!:. STATION HILL BLANCHOT READER FOREWORD here. Beginning with a kind of history of this question, Blanchot ob fictional writings-once one has encountered it, chat is co say, in the serves that, strangeness of their language: a force, at times, chat one associates with sacred texts or forms of mythopoiesis, a clarity, at ocher moments, that Since Mallarme ... there has come to light the experience of some carries a sovereign humor at grips with the impossible, throughout a thing one conrinues to call, but with a renewed seriousness, and haunting presence and an enigmatic grace. "The words spoke alone," moreover, in quotation marks, "literature." Essays, novels, po of ems seem to be there and to be written only in order to allow the the narrator remarks in The Madness rlze Day. Once one has heard this labor of literature ... to accomplish itself, and through this labor to speech and the silence that attends it, one cannot also help hearing a let the question come forth: "What is at stake in the fact that some .. literary" pull in essays like "Literature and the Right to Death," a thing like art or literature should exist?" theoretical and critical text that is also of the highest dialectical subtlety and rigor in its exploration ofche "two versions of the imaginary." And The question, he suggests, has been obscured by a secular tradition one cannot then help hearing it elsewhere: in philosophy, or in any of aestheticism. Nevertheless, he continues, discourse that draws from what "speaks" in language. From rl1e facr of language as it is presented by Blanchet, in ocher words, the question, Lit:.rary wo~k and research-let us retain this qualifying "liter "What is at stake in the fact that such texts exist?" leads into a general ary -contribute to shake the principles and the truths sheltered by literature. This work, in correlation with certain possibilities questioning about language itself, a questioning that cannot avoid the offered by knowledge, by discourse and by political struggle, has problematic of writing as authors such as Heidegger and Derrida have brought forth, though not for the first time ... the question of lan helped define it in their respective ways. From there, it is a small step guage, and then, through the question of language. the question co the fundamental questions enumerated in the passage from Blanchot's that perhaps ov:rrums it and comes together in the word, today "Note," including that of "another way of being in relation." openly and easily allowed ... : writing, "this mad game of writ Blanchet refers in his "Note," as we have seen, to "the exigency of ing. "3 writing"-the genitive both subjective and objective. He refers else . :·writing, the exigency of writing," devoted seemingly only to itself where, and with a more ethical inflection, to "the exigency of another 111 its slow emergence (so that it could be confused, we might add, with relation,"~ implying with the same ambiguity of the genitive and the the fonnalist celebrations of literariness that have received renewed fa same notion of writ1ng that the relation in question both demands or vor in the academy), has brought out "entirely other possibilities": forms "requires" and is required. What is chis relation? The reader will dis of "being in relation" that carry in co the incommensurability of their cover its trace at the thematic level perhaps first in the arresting de movements, "first the idea of God, of the Self, of the Subject, then of scriptions of an encounter with a radical alterity. Thomas, for example, Truth and the One, then finally the idea of the Book and the Work." knows an endless becoming-ocher in exposure to what Blanchet names near the end ofT/iomas rlze Obswre "the supreme relation." We wimess En~ugh to get us all locked up (to recall The Madness of rhe Day). Bue this "knowledge" in scene after scene of this work: scenes of struggle, such is the arc of questioning we might envision, one arc among the flight, or ab:indon, in each case involving the presence of an absence ~an.y that cannot be foreseen. And the spring for this movement of ques that Blanchet names in his more theoretical statements (and with t10111ng, I w~uld like to emphasize, may be the cumulative and multiple LCvinas), the i/ y a. 'i But this knowledge is exhibited nowhere more for~e.of t.he htera:y works gathered in this collection-a force that proves poignantly, perhaps, than in the opening of the monologue that follows decisive. m breaking through the customary relation to "literature" and the account of Anne's agony, and in what Thomas does not fully bring prompti.ng the reader to ask about the implications of the fact that such to speech: his relation co Anne's gift of her dying. Is his own "death" in texts eXJst. I do not believe one can hear literary language in the same these pages not intimately bound to hers? The "knowledge" co which way once one has encountered this question in and through Blanchot's I have referred, in any case, is a dying. as lllanchot chematizes it most xviii XIX