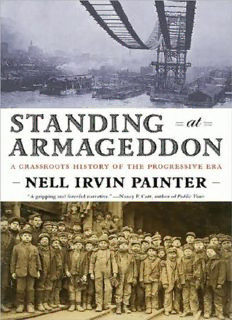

Standing at Armageddon: A Grassroots History of the Progressive Era PDF

Preview Standing at Armageddon: A Grassroots History of the Progressive Era

STANDING AT ARMAGEDDON THE UNITED STATES, 1877–1919 Also by Nell Irvin Painter Creating Black Americans: African-American History and Its Meanings, 1619 to the Present Southern History Across the Color Line Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol The Narrative of Hosea Hudson: His Life as a Negro Communist in the South Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (editor) Narrative of Sojourner Truth (editor) STANDING AT ARMAGEDDON THE UNITED STATES 1877 — 1919 Nell Irvin Painter Copyright © 2008, 1987 by Nell Irvin Painter All rights reserved First published as a Norton paperback 1989; reissued 2008. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Painter, Nell Irvin. Standing at Armageddon. Includes bibliographies 1. United States-History-1865-1921. 2. United States-Social conditions-1865-1919. I. Title. E661.P33 1987 973.8 86-33111 ISBN 978-0-39333192-9 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www.wwnorton.com W.W. Norton & Company Ltd. Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT FOR FRANK AND MADELINE FREIDEL Contents Preface to the 2008 Edition Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1 THE TOCSIN SOUNDS Chapter 2 THE GREAT UPHEAVAL Chapter 3 REMEDIES Chapter 4 THE DEPRESSION OF THE 1890s Chapter 5 THE WHITE MAN’S BURDEN Chapter 6 PROSPERITY Chapter 7 RACE AND DISFRANCHISEMENT Chapter 8 WOMAN SUFFRAGE AND WOMEN WORKERS Chapter 9 THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Chapter 10 WARS Chapter 11 THE EUROPEAN WAR TAKES OVER 306 Chapter 12 THE GREAT UNREST Epilogue Afterword Index Preface to the 2008 Edition SO MANY strange names and terms! Nineteenth-century history can seem so foreign: the Knights of Labor, Henry George, the graduated income tax, the People’s Party, the protective tariff. But when you take a second look—when you grasp the symbolic meaning behind the words—you see that unfamiliar names attach to familiar concerns. In our present-day return to the Gilded Age, we realize the issues of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries never really died. The old issues, in fact, are with us still. As Henry George said way back in 1879, the “unequal distribution of wealth” is the curse of our times. More than a century ago, thoughtful Americans pondered the meaning of wealth generated by a modern economy. They asked how it could be that the people who worked the hardest were the poorest, but the people who seemed not to work at all rolled in dough. How could it be that political power served the people with the most but did so little for the people with the least? What is— what should be—the relation between the power of money and the power of the people? In the last generation, Americans (among other people) have faced old and new crises. An energy crisis remains with us as we grapple with global warming. We now call hard times recessions, but their toll in human suffering remains. We used to be able to grow out of every crisis at home and send in friendly GIs to help out the people overseas, but wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq have divided the American people without producing the victorious finale of the “good war” of the 1940s. Today, as when the war in question was the Philippine insurrection, Americans argue over the wisdom of trying to improve another country by occupying it. William Jennings Bryan’s question from 1899 bears repeating: Is the United States a democracy or an empire? Wars are with us still, and their costs in money and blood remain staggering. As Americans asked in 1917, they wonder now: Who should pay and how? Who should serve in the battlefield? Who are the enemy at home and abroad? These pressing issues of the First World War remain pressing issues today. The enemies, though, have changed, and the threat of terrorism seems to be everywhere. We no longer trade in “red scares,” because the Soviet Union no longer exists and the Cold War is over. But we still question the trade-offs between freedom and security. Is the loss of American freedom the cost of between freedom and security. Is the loss of American freedom the cost of vigilance, and who decides who will pay? At the end of the First World War and in the midst of the Great Unrest, a Chicago journal predicted that “unless the issue is decided once and for all now, through the firmness and courage of the American people, Americanism for a time at least will perish from the face of the earth and the war will have been fought in vain.” Whether the challenge is economic hard times, religious antagonism, or the gap between the rich and the poor, this warning from nearly a century ago still rings in our ears.

Description: