Spanish traditionalism and French traditionalistic ideas of the nineteeth century in Spain PDF

Preview Spanish traditionalism and French traditionalistic ideas of the nineteeth century in Spain

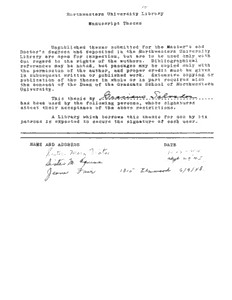

Northwestern University Library Manuscript Theses Unpublished theses submitted for the Master’s and Doctor’s degrees and deposited in the Northwestern University Library are open for inspection, but are to be used only with duo regard to the rights of the authors. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may be copied only with the permission of the author, and proper credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. Extensive copying or publication of the theses in whole or in part requires also the consent of the Dean of the Graduate School of Northwestern University. This thesis by has been used by the following persons, whose signatures attest their acceptance of the above restrictions* A Library which borrows this thesis for use by its patrons is expected to secure the signature of each user. NAME AND ADDRESS DATE r7 , rs ■ t / 3 /S * Ua^\j NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY SPANISH TRADITIONALISM AND FRENCH TRAD ITI ON ALIS TIC IDEAS OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY IN SPAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES BY GRACIANO SALVADOR EVANSTON, ILLINOIS AUGUST, 1943 ProQuest Number: 10101914 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10101914 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 < i 'ft') r/ / o i TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD PART ONE INTRODUCTION The origins of the traditionalistic move ment in Spain; historical background. CHAPTER I French antecedents of Spanish traditional ism. CHAPTER II Traditionalism in philosophy; Jaime Luciano Balmes. CHAPTER III Juan Donoso Cortes. PART TWO Traditionalism in Literature CHAPTER IV The press; the drama: Jose Zorrilla, Adelardo Lopez de Ayala, and Manuel Tamayo y Baus. CHAPTER V The novel: Fernan Caballero, Pedro Anto nio de Alarcon. The critics: Marcelino Menendez y Pelayo and Angel Ganivet. CHAFTER VI Regionalism: its nature, its significance and its development. Its most outstanding exponents: Fernan Caballero and Jose Maria de Pereda. CONCLUSION ii FOREWORD 11 | j| In his Panorama de la litterature esoagnole. the Hispar- sj Inist, Jean Cassou, wrote the following: "De merae que l*on I! !|distingue deux Frances, la France traditionaliste et la il ii , ^ !France revolutionnaire, de meme on peut distinguer deux ii s! IjEspagnes, l'Espagne religieuse et l'Espagne lafque." There |jis a great deal of truth in this statement, first, as to ;i |the duality of the Spanish nation, a nation with a divided ■ j soul: the old and the new Spain, the traditionalist and S) the liberal; secondly, as to the implication that as it is 1 in France so it is also in Spain. !i '*i We are here concerned with traditionalist Spain. The !! ihistory of Spanish liberalism, in its multiple phases, has already been written. Many are those writers who have interested themselves in this subject and dealt with it at I jjgreat length, but the history of Spanish traditionalism is ii ||still to be written. I The bibliography of this subject of traditionalism is II fpractically nonexistent. As yet there is no work which jjcompletely covers the relations between France and Spain !i during the nineteenth century, such as the monograph of j■ ii ■ipaul Merime,e regarding Franco-Spanish relations in the 8 1 ||eighteenth century . Traditionalism, the touchstone of 1)1. L 1 Influence francaise au dix-huitieme siecle (Paris, 1936) . |Spanish political, Bocial, and literary struggles for the I I last one hundred and thirty years, has not been treated in jj |any systematic or comprehensive way. While valuable and s ppertinent remarks, as well as abundant, informative ma ll i[ terial on the subject may be gathered from much of the jj jjwork of Marcelino Menendez y Pelayo, especially the third I ~ Is volume of his Historia de los heterodoxos espanoles. his- s •tories of Spanish philosophy, as well as histories of Span- ■j |] ish literature, either ignore the matter of traditionalism P |altogether, or dismiss it with one or two short paragraphs. ) An article on Spanish traditionalism was written by ii ; Gumersindo Laverde in 1868 and reprinted by Menendez y ■ j Pelayo in the appendix of the third volume of his monu- jj ;!mental work, La ciencia espanola. The article, however, is I very brief, and its purpose was rather to show possible |i j Spanish sources for French traditionalism. An article of |considerable length is found under the word Tradicionalismo jj t I in the Enciclopedia Espasa. But the article, long though jj ;j it is, deals mainly with the political aspects of tradi- 1tionalism, especially as represented by the Carlist movement ;j Furthermore, a distinguished hispanist, Edgar Allison l! j! Peers, who has devoted a considerable amount of research to l| Franco-Hispanic relations, principally with reference to I! ij the Romantic movement, expresses the opinion that Chateau— briand exercised no fundamental influence on any Spanish |i ii I writer of note, with the exception of Enrique Gil y Carrasco iii jAgain the editor of one of Pereda's major works, Ralph 1 iEmerson Bassett, asserts that, although Pereda was a man ;j |of wide culture, he was singularly immune to outside in- j| jjfluences. Our investigation of the problems has convinced ;! I us that such opinions are ill-founded and need to be re- |vised. j! :j i| Our main purpose, however, is not to write the history I of traditionalism in Spain, but to analyze it as a doctrine 1 i |and as a positive force that has been, so to speak, the !axis of Spanish political, social and literary life for jalmost a century and a half; to ascertain the extent of :the influence, direct or indirect, if any, which French ; i traditionalists may have exercised upon the Spanish tra- i jditionalists of the nineteenth century; and, likewise, to jdiscuss certain modifications, which Spanish theorists may have developed, independently of their French predecessors. ■js ;j We are glad to take this opportunity to express our •I jj sincere thanks to Professor Alphonse Roche, who suggested jto us the subject of this dissertation and has directed jour research. We are also grateful to Professor Edwin B. jPlace, who has served as co-director, and to our colleagues, Professors James. J. Young and Julius Kuhinka of Loyola ;University, for their valuable criticism of the English style of the present study. The responsibility, however, Ifor its content and for any errors that may appear therein, jrests solely upon the writer. ii - 1 - ; INTRODUCTION r. The year 1700 constituted an eventful date in the annals of the Spanish nation; it marked a major turning I point in its history* Politically, it simply meant a i change of dynasty, a Bourbon instead of a Hapsburg; but practically, and in the words of the M the Pyrenees were levelled, no more to form a barrier between the two sister nations, France and Spain.'1 The Du-fyfe of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV, whom Charles II of Spain had appointed in his last testament as the heir to the Spanish throne, came in 1701 to take possession of it, ■under the name of Philip V* The Bourbon dynasty became at once the channel, so to speak, through which European thought and culture began to filter into self-isolated Spain. A change of dynasty necessarily brought with it a change of ideas, of outlook, of purpose, of methods, and of personnel* Spain was thus brought under direct French influence. This influence was not limited to the political field; it was extended to nearly every sphere of Spanish life and activity. This is manifested by the many institu tions founded, which were modelled on French patterns— literary, social, and economic; as well as by the large number of professors, engineers, architects, and even politicians who were imported from France in order to 2 i ! direct the new academies, schools, clubs, societies, and |i | various other enterprises. The number of books, especially i1 ! French, translated into Spanish throughout this period is I I also quite considerable1. The influence of new ideas i P ;j from beyond the Pyrenees, Jansenistic , on the one hand, Ii jj and Encyclopaedic^, on the other, becomes gradually more ■ pronounced, especially under the successors of Philip V. Moreover, this trend of affairs in matters so vitally af- jj fee ting the great majority of the nation was seconded by ;many of the social and intellectual elite of the country, ! M 1. The Royal Library with Father Robinet, confessor of ii the king, at its head, was founded in 1711; the Spanish jAcademia de la Lengua in 1713; the Academia de Bellas Artes S of Barcelona in 1729; the Academia de Medicina in 1734; the !Academia de la Historia in 1738. The Diario de los litera- I tos. modelled on the French Joumal des savants, was founded |in 1737; the Academia del buen gusto, presided over by the ;Countess of Lemos, is of 1749. :1 According to Paul Merimee (op. oft., pp. 21 ff.), the j catalog of the Royal Library showed, before the nineteenth century the following: nine editions of Descartes and of |Pascal; eighteen editions of the latterfs Provinciales; I seven editions of Rousseau; nineteen editions of the com- jplete works of Voltaire. See also Pedro Aguado Beyle, Manual de historia de Espana, vol. II (Bilbao. 1929). p. 5/9 | / • 2. Difficulties with the Vatican started as early as 1709 when by decree Philip V closed the Nunciatura and forbade |all communications with Rome. 3. "Voltaire," says Merimee, "est le philosophe dont l'in- jfluence fut la plus considerable; on lit ses oeuvres^ on is*inspire de ses principes litteraires...; il ecrit a Aranda, Olavide, Mayans; on lui envoie des produits de l'Espagne... jet on s'affranchit a son exemple, de superstitions en cher- Schant a ruiner 1*autorite deja affaiblie de l^Eglise Catho- lique...aussi l’Espagne a~t—elle subi profondement l*in- ifluence des philosophes, encyclopedistes et economistes ifran9ais.K Op. cit., pp. 69 ff.