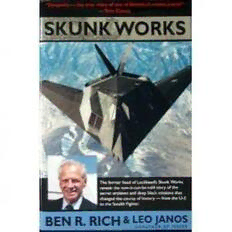

Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed PDF

Preview Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed

Begin Reading Table of Contents Photos Newsletters Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the men and women of the Skunk Works, past, present, and future ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T HE AUTHORS wish to acknowledge the contributions of various friends, co-workers, and former colleagues who enriched the pages of this book with their perspectives and recollections. Special thanks to Nancy Johnson and to Lockheed’s CEO, Dan Tellep, for providing access to Kelly Johnson’s logbooks and to former colleagues Sherm Mullin, Jack Gordon, Ray Passon, Dennis Thompson, Willis Hawkins, and Steve Shobert, who provided their expertise and advice through the manuscript process. Thanks also to Col. (ret.) Barry Hennessey, Pete Eames, Air Force historian Richard Hallion, and Don Welzenbach of the CIA. Numerous Skunk Workers contributed their insights and memories. Among them: Dick Abrams, Ed Baldwin, Alan Brown, Buddy Brown, Norb Budzinske, Fred Carmody, Henry Combs, Jim Fagg, Bob Fisher, Tom Hunt, Bob Klinger, Alan Land, Tony LeVier, Red McDaris, Bob Murphy, Norm Nelson, Denys Overholser, Bill Park, Tom Pugh, Jim Ragsdale, Butch Sheffield, Steven Schoenbaum, and Dave Young. We are particularly grateful for the participation of Air Force and CIA pilots, past and present: Bob Belor, Tony Bevacqua, William Burk Jr., Jim Cherbonneaux, Buz Carpenter, Ron Dyckman, Barry Horne, Joe Kinego, Marty Knutson, Joe Matthews, Miles Pound, Randy Elhorse, Jim Wadkins, Al Whitley, and Ed Yeilding. Significant too were the contributions of the current secretary of defense, William J. Perry, and former secretaries, Donald H. Rumsfeld, James R. Schlesinger, Harold Brown, and Caspar Weinberger; also former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General David Jones, former Air Force Secretary Don Rice, the CIA’s Richard Helms, Richard Bissell, John McMahon, Albert “Bud” Wheelon, and John Parangosky; Generals Leo Geary, Larry Welch, Jack Ledford, and Doug Nelson; National Security advisers Walt Rostow and Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Albert Wohlstetter, formerly of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. For obtaining photos and reference sources, appreciation to Lockheed’s Denny Lombard and Eric Schulzinger, Bill Lachman and Bill Working of the Central Imaging Office, Jay Miller of Aerofax, and Tony Landis. For reference material, a salute to aviation writers Chris Pocock and Paul Crickmore. For help often above and beyond the call of duty, our gratitude to Diana Law, Myra Gruenberg, Debbie Elliot, Karen Rich, Bert Reich, Ben Cate, and in particular to my son, Michael Rich, for his insights and suggestions, and to our wives, Hilda Rich and Bonnie Janos, for their patience and support. Finally, our affectionate appreciation to our agent, Kathy Robbins, and to our editor, Fredrica Friedman, executive editor of Little, Brown. Los Angeles, January 1994 1 A PROMISING START It’s August 1979 on the scorching Nevada desert, where Marines armed with ground-to-air Hawk missiles are trying to score a “kill” against my new airplane, an experimental prototype code-named Have Blue. We in the Skunk Works have built the world’s first pure stealth fighter, which is designed to evade the Hawk’s powerful radar tracking. The Marines hope to find Have Blue from at least fifty miles away and push all the right buttons so that the deadly Hawks will lock on. To help them, I’ve actually provided Have Blue’s flight plan to the missile crew, which is like pointing my finger at a spot in the empty sky and saying, “Aim right here.” All they’ve got to do is acquire the airplane on radar, and the homing system inside the Hawk missile will do the rest. Under combat conditions, that airplane would be blasted to pieces. If that defensive system locks on during this test, our experimental airplane flunks the course. But I’m confident that our stealth technology will prove too elusive for even this Hawk missile’s powerful tracking system (capable of detecting a live hawk riding on the thermals from thirty miles away). What makes this stealth airplane so revolutionary is that it will deflect radar beams like a bulletproof shield, and the missile battery will never electronically “see” it coming. On the Hawk’s tracking system, our fighter’s radar profile would show up as smaller than a hummingbird’s. At least, that’s what I’m betting. If I’m wrong, I’m in a hell of a bind. Half the Pentagon’s radar experts think we at the Skunk Works have achieved a stealth technology breakthrough that will revolutionize military aviation as profoundly as the first jets did. The other half thinks we are deluding ourselves and everyone else with our radar test claims. Those cynics insist that we are trying to pull a fast one—that we’ll never be able to duplicate on a real airplane the spectacular low visibility we achieved on a forty-foot wooden model of Have Blue, sitting atop a pole on a radar test range. Those results blew away most of the Air Force command staff. So this demonstration against the Hawk missile is the best way I know to shut up the nay-sayers definitively. This test is “In your face, buddy,” to those bad-mouthing our technology and our integrity. My test pilot teased me that Vegas was giving three to two odds on the Hawk over Have Blue. “But what do those damned bookies know?” he added with a smirk, patting my back reassuringly. Because our stealth test airplane has been under the tightest security, we’ve had to deceive the Marines into thinking that the only thing secret about our airplane is a black box it’s supposed to be carrying in its nose that emits powerful beams to deflect incoming radar. Of course, that’s all bogus. No such black box aboard, no beams involved. The invisibility comes entirely from the airplane’s shape and its radar-absorbing composite materials. The missile crew will monitor the test on their radar scope inside their windowless command van, but a young sergeant standing beside me will be able to verify that, despite the blank screen, an airplane indeed flew overhead. God knows what he will think seeing our airplane in the sky, a weird diamond-shaped UFO, looking as if it escaped from a trailer for a new George Lucas Star Wars epic. I check my watch. Eight in the morning. The temperature already in the nineties, heading toward a predicted high of one-twenty F. Have Blue should be well inside the missile’s radar track, heading for us. And in a few moments I spot a distant speck growing ever larger in the milky blue sky. I watch Have Blue through my binoculars as it flies at eight thousand feet. The T-38 chase plane, which usually flies on its wing in case Have Blue develops problems and needs talking down to a safe landing, is purposely following miles behind for this test. The radar dish atop the van hasn’t moved, as if the power has been turned off. The cluster of missiles, which normally would be swiveling in the launcher, locked on by radar to the approaching target, are instead pointing aimlessly (and blindly) toward distant mountains. The young sergeant stares in disbelief at the sightless missiles, then gapes as the diamond-shaped aircraft zips by directly above us. “God almighty,” he exclaims, “whatever that thing was, sir, it sure is carrying one hell of a powerful black box. You jammed us dead.” “Looks that way.” I say and grin. I head to the command van, and a cold blast of the air-conditioning greets me as I step inside. The Marine crew is still seated around their electronic gear with stolid determination. Their scope screen is empty. They’re waiting. As far as they know, nothing has yet flown into their radar net. Suddenly a blip appears. It’s moving quickly west to east in the exact coordinates of Have Blue. “Bogie acquired, sir,” the radar operator tells the young captain in charge. For a moment I’m startled, watching a moving blip that should not be. And it is big, unmistakable. “Looks like a T-38, sir,” says the operator. I exhale. The T-38 chase plane is being acquired by their radar detection. The radar operator has no idea that two airplanes should be on his scope—not one—and that he never did pick up Have Blue as it flew overhead. “Sorry, sir,” the young captain says to me with a smug sneer. “Looks like your gizmo isn’t working too good.” Had this been a combat situation, the stealth fighter could have used high-precision, laser- guided bombs against the van and that smug captain would never have known what hit him. Might have taught him a lesson in good grammar too. The van door opens and the young sergeant steps into the dark coolness, still looking as if he had hallucinated in the desert heat—seeing with his own eyes a strange diamond apparition that his missiles failed to lock onto. “Captain,” he began, “you won’t believe this…” T HREE AND A HALF years earlier, on January 17, 1975, I drove to work in downtown Burbank, California, as I had for the past twenty-five years, only now I parked for the first time in the boss’s slot directly in front of an unmarked two-story windowless building that resembled a concrete blockhouse, in plain view of the main runway at Burbank’s busy Municipal Airport. This was Lockheed’s “Skunk Works,” which, throughout the long, tense years of the cold war, was one of the most secret facilities in North America and high on the targeting list of the Soviet Union in the event of nuclear war. Russian satellites regularly overflew our parking lot in the midst of Lockheed’s sprawling five-square-mile production complex, probably counting our cars and analyzing how busy we were. Russian trawlers, just outside territorial limits off the southern California coastline, trained powerful eavesdropping dishes in our direction to monitor our phone calls. We believed the KGB knew our key phone numbers, and computerized recording devices aboard those trawlers probably switched on when those phones rang. U.S. intelligence intercepted references to “the Skunk Works” regularly from Soviet satellite communications simply because there was no Russian translation for our colorful nickname. Our formal name was Lockheed’s Advanced Development Projects. Even our rivals would acknowledge that whoever ran the Skunk Works had the most prestigious job in aerospace. Beginning with this mild day in January, that guy was me. I was fifty years old and in the pink. Most Skunk Workers were handpicked by our just retired leader, Kelly Johnson, one of the reigning barons of American aviation, who first joined Lockheed in 1933 as a twenty-three-year-old fledgling engineer to help design and build the Electra twin-engine transport that helped put the young company and commercial aviation on the map. By the time he retired forty-two years later, Kelly Johnson was recognized as the preeminent aerodynamicist of his time, who had created the fastest and highest-flying military airplanes in history. Inside the Skunk Works, we were a small, intensely cohesive group consisting of about fifty veteran engineers and designers and a hundred or so expert machinists and shop workers. Our forte was building a small number of very technologically advanced airplanes for highly secret missions. What came off our drawing boards provided key strategic and technological advantages for the United States, since our enemies had no way to stop our overflights. Principal customers were the Central Intelligence Agency and the U.S. Air Force; for years we functioned as the CIA’s unofficial “toy- makers,” building for it fabulously successful spy planes, while developing an intimate working partnership with the agency that was unique between government and private industry. Our relations with the Air Force blue-suiters were love-hate—depending on whose heads Kelly was knocking together at any given time to keep the Skunk Works as free as possible from bureaucratic interlopers or the imperious wills of overbearing generals. To his credit Kelly never wavered in his battle for our independence from outside interference, and although more than one Air Force chief of staff over the years had to act as peacemaker between Kelly and some generals on the Air Staff, the proof of our success was that the airplanes we built operated under tight secrecy for eight to ten years before the government even acknowledged their existence. Time and again, our marching orders from Washington were to produce airplanes or weapons systems that were so advanced that the Soviet bloc would be impotent to stop their missions. Which was why most of the airplanes we built remained shrouded in the deepest operational secrecy. If the other side didn’t know these aircraft existed until we introduced them in action, they would be that much farther behind in building defenses to bring them down. So inside the Skunk Works we operated on a tight-lipped need-to-know basis. I figured that an analyst for Soviet intelligence in Moscow probably knew more about my Skunk Works projects than my own wife and children. Even though we were the preeminent research and development operation in the free world, few Americans heard of the Skunk Works, although their eyes would light with recognition at some of our inventions: the P-80, America’s first jet fighter; the F-104 Starfighter, our first supersonic jet attack plane; the U-2 spy plane; the incredible SR-71 Blackbird, the world’s first three-times-the-speed-of-sound surveillance airplane; and the F-117A stealth tactical fighter that many Americans saw on CNN scoring precision bomb strikes over Baghdad during Operation Desert Storm. These airplanes, and other Skunk Works projects that were unpublicized, shared a common thread: each was initiated at the highest levels of the government out of an imperative need to tip the cold war balance of power in our direction. For instance, the F-104, nicknamed “The Missile With the Man In It,” was an incredibly maneuverable high-performance Mach 2 interceptor built to win the skies over Korea in dogfights against the latest high-performance Soviet MiGs that had been giving our combat pilots fits. The U-2 spy plane overflew the Soviet Union for four tense years until luck ran out and Francis Gary Powers was shot down in 1960. The U-2 was built on direct orders from President Eisenhower, who was desperate to breach the Iron Curtain and discover the Russians’ potential for launching a surprise, Pearl Harbor–style nuclear attack, which the Joint Chiefs warned could be imminent. And it is only now, when the cold war is history, that many of our accomplishments can finally be revealed, and I can stop playing mute, much like the star-crossed rabbi who hit a hole in one on the Sabbath. I had been Kelly Johnson’s vice president for advanced projects and his personal choice to succeed him when he was forced to step down at mandatory retirement age of sixty-five. Kelly started the Skunk Works during World War II, had been Lockheed’s chief engineer since 1952, and was the only airplane builder ever to win two Collier Trophies, which was the aerospace equivalent of the Hollywood Oscar, and the presidential Medal of Freedom. He had designed more than forty airplanes over his long life, many of them almost as famous in aviation as he was, and he damned well only built airplanes he believed in. He was the toughest boss west of the Mississippi, or east of it too, suffered fools for less than seven seconds, and accumulated as many detractors as admirers at the Pentagon and among Air Force commanders. But even those who would never forgive Johnson for his bullying stubbornness and hair- trigger temper were forced to salute his matchless integrity. On several occasions, Kelly actually gave back money to the government, either because we had brought in a project under budget or because he saw that what we were struggling to design or build was just not going to work. Kelly’s motto was “Be quick, be quiet, be on time.” For many of us, he was the only boss we had ever known, and my first day seated behind his huge desk in the big three-hundred-square-foot corner office where Kelly had commanded every aspect of our daily operations, I felt like a three-and-half-foot-tall impostor, even though my kingdom was a windowless two-story headquarters building housing three hundred engineers, supervisors, and administrators, who operated behind thick, eavesdrop-proof walls under guard and severe security restrictions in an atmosphere about as cheery as a bomb shelter. The unmarked building was adjacent to a pair of enormous production hangars, with a combined 300,000 square feet of production and assembly space. During World War II, those hangars were used to build P- 38 fighters, and later on, the fleet of Lockheed Constellations that dominated postwar commercial aviation. My challenge was to keep those six football fields’ worth of floor space humming with new airplane production and development. The twin giant hangars were three stories high and dwarfed four or five nearby buildings that housed our machine shops and parts factories. Aside from a guard booth that closely screened and monitored all visitors driving into our area, there were no visible signs of the restricted Skunk Works operation. Only those with a real need to know were directed to the location of our headquarters building, which had been built for Kelly in 1962. As austere as the concrete-and-steel facility was, it seemed like a palace to those fifty of us who, back in the early 1950s, had been crammed into the small drafty offices of the original Skunk Works in Building 82, less than three hundred yards away, which was an old bomber production hangar left over from World War II and still used on some of our most sensitive projects. I enjoyed the goodwill of my colleagues because most of us had worked together intimately under tremendous pressures for more than a quarter century. Working isolated, under rules of tight security, instilled a camaraderie probably unique in the American workplace. I was Kelly’s right-hand man before succeeding him, and that carried heavy freight with most of my Skunk Works colleagues, who seemed more than willing to give me the benefit of the doubt as their new boss—and keep those second guesses to a minimum for at least the first week or so. But all of us, from department heads to the janitorial brigade, had the jitters that followed the loss of a strong father figure like Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, who had taken care of us over the years and made us among the highest-paid group in aerospace, as well as the most productive and respected. Daddy, come back home! I began by loosening the leash on all my department heads. I told them what they already knew: I was not a genius like Kelly, who knew by experience and instinct how to solve the most complex technical problems. I said, “I have no intention of trying to make all the decisions around here the way that Kelly always did. From now on, you’ll have to make most of the tough calls on your own. I’ll be decisive in telling you what I want, then I’ll step out of your way and let you do it. I’ll take the crap from the big wheels, but if you screw up I want to hear it first.” I left unspoken the obvious fact that I could not be taking over at a worse time, in the sour aftermath of the Vietnam War, when defense spending was about as low as military morale, and we were down to fifteen hundred workers from a high of six thousand five years earlier. The Ford administration still had two years to run, and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was acting like a guy with battery problems on his hearing aid when it came to listening to any pitches for new airplanes. And to add anxiety to a less than promising business climate, Lockheed was then teetering on the edge of corporate and moral bankruptcy in the wake of a bribery scandal, which first surfaced the year before I took over and threatened to bring down nearly half a dozen governments around the world. Lockheed executives admitted paying millions in bribes over more than a decade to the Dutch (Crown Prince Bernhard, husband of Queen Juliana, in particular), to key Japanese and West German politicians, to Italian officials and generals, and to other highly placed figures from Hong Kong to Saudi Arabia, in order to get them to buy our airplanes. Kelly was so sickened by these revelations that he had almost quit, even though the top Lockheed management implicated in the scandal resigned in disgrace. Lockheed was convulsed by some of the worst troubles to simultaneously confront an American corporation. We were also nearly bankrupt from an ill-conceived attempt to reenter the commercial airliner sweepstakes in 1969 with our own Tristar L-1011 in competition against the McDonnell Douglas DC-10. They used American engines, while we teamed up with Rolls-Royce, thinking that the Anglo- American partnership gave us an advantage in the European market. We had built a dozen airliners when Rolls-Royce unexpectedly declared bankruptcy, leaving us with twelve hugely expensive, engineless “gliders” that nobody wanted. The British government bailed out Rolls-Royce in 1971, and the following year Congress very reluctantly came to our rescue by voting us $250 million in loan guarantees; but our losses ultimately reached a staggering $2 billion, and in late 1974, Textron Corporation almost acquired all of Lockheed at a “fire sale” price of $85 million. The Skunk Works would have been sold off with the corporation’s other assets and then tossed into limbo as a tax write-off. I had to get new business fast or face mounting pressure from the corporate bean counters to unload my higher-salaried people. Kelly was known far and wide as “Mr. Lockheed.” No one upstairs had dared to cross him. But I was just plain Ben Rich. I was respected by the corporate types, but I had no political clout whatsoever. They demanded that I be a hell of a lot more “client friendly” than Kelly had been. It was an open secret in the industry that Kelly had often been his own worst enemy in his unbending and stubborn dealings with the blue-suiters. Until they had run afoul of our leader, not too many two- or three- star generals had been told to their faces that they didn’t know shit from Shinola. But smoothing relations with Pentagon brass would only serve to push me away from the dock—I had a long hard row ahead to reach the promised land. If the Skunk Works hoped to survive as a viable entity, we somehow would have to refashion the glory years last enjoyed in the 1960s when we had forty-two separate projects going and helped Lockheed become the aerospace industry leader in defense contracts. I knew there were several powerful enemies of the Skunk Works on Lockheed’s board who would close us down in a flash. They resented our independence and occasional arrogance, and suspected us of being profligate spenders hiding our excesses behind screens of secrecy imposed by our highly classified work. These suspicions were fueled by the fact that Kelly usually got whatever he wanted from Lockheed’s board—whether it was costly new machinery or raises for his top people. Nevertheless, Kelly actually was as tightfisted as any beady-eyed New England banker and would raise hell the moment we began dropping behind schedule or going over budget. Knowing that I didn’t have much time to find new business, I flew to Washington, hat in hand, with a fresh shoeshine and a brave smile. My objective was to convince General David Jones, the Air Force chief of staff, of the need to restart the production line of the U-2 spy plane. It was a long-shot attempt, to say the least, because never before in history had the blue-suiters ever reopened a production line for any airplane in the Air Force’s inventory. But this airplane was special. I have no doubt that fifty years from