She-Calf and Other Quechua Folk Tales PDF

Preview She-Calf and Other Quechua Folk Tales

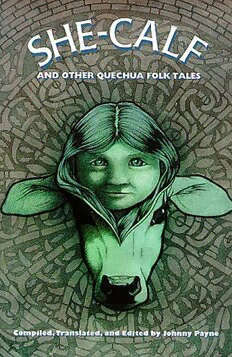

She-Calf and Other Quechua Folk Taler Compiled, Translated, and Edited by Johnny Payne UNIVERSITY OE NEW MEXICO PRESS Albuquerque Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data She-calf and other Quechua folk tales / compiled, translated, and edited by Johnny Payne, p.. cm. English and Quechua ISBN 0-8263-2195-X (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Quechua Indians— Folklore. 2. Tales— Peru. 3. Quechua language— Texts. I. Payne, Johnny, 1958- F3429.3.F6 S47 2000 398.2'o89’98323o85 21— dc21 99-°4353° All introductions and English text of stories ©2000 by the University of New Mexico Press First edition All rights reserved. ISBN-13:978-0-8263-2195-4 A Spanish/Quechua edition appeared as Cuentos Cusqueños published by the Centro de estudios rurales andinos “Bartolome de las Casas” (Cusco, Peru 1984; revised © 1999). The Quechua text from the revised edition is reproduced in this book with the permission and cooperation of the Centro de estudios rurales andinos and its editor Sr. Andres Chirinos. Contents An Interloper’s Introduction / The Eagles Who Raised a Child 15 2CJ The Woman Who Tended Ducks The She-Calf The Condor 57 The Quena The Clever Priest 69 The Baker and the Lovers 75 The Carpenter’s Wife S3 The Shepherdess 89 The Pastureland Girl 95 The Hacienda Owner’s Daughter 103 in The Deserter Watch Dog and Bean Blossom 117 Wayrurkumacha and Chinchirkumacha 125 The Man-Bear I31 The Corn-Beer Seller 141 What the Gringo Ate 147 The Stupid Gringo 151 The Rascal Priest *55 The Idiot (two stories) 161 The Fox and the Mouse (four stories) l 73 The Boy Who Didn’t Want to Eat 199 The Old Crone 2 07 The Farewell 215 The Coffin Contest 221 The Wand 2 3 1 The Promise 237 The River-Siren 251 An Apparition 2 57 Child Jesus, Yarn-Spinner 263 An Interlopero Introduction The fascination of the ethnographer, in some respects, is not unlike that of the indigenous dweller who sits listening to the story or oral his tory being told. In Quechua folk tales, the narrative act has its own spe cial verb tense, -sqa, suggesting that this encounter grants freedoms be yond the everyday, and, at the same time, requires strict observance of injunctions and prohibitions. The listener exists in this sphere as something like that vulnerable young child who is bathed with scented soap, anointed with perfume, and placed in a spanking-new bed with candies and sweetmeats, to await the nocturnal visit of a magical calf. The child, attracted and fearful all at once, doesn’t have any choice but to give himself over to what is about to happen. However keen his expectation and desire, there are specific limits on what he may or may not do or say. If he allows himself to believe that he is fully in control of his destiny, then he understands nothing about the world of magic. The act of initiation, the rite of passage, once it is embarked on, has little to do with one’s own free will. The encounter between child and she-calf, told by Quechua storyteller Teodora Paliza, goes like this: At midnight, she heard the lament from the street corner, mak ing its way toward the front door. “Aaaaaaahhh! ” The she-calf opened the door slowly, and crept into the room. Beautiful candles were burn ing. She sniffed all that had been prepared, just a whiff. When she was done, she approached the boy’s bed. And with a whoosh! she i slipped out of her calfskin. When she had slipped out of it, she climbed up on one corner of the bed. It is not always easy to say precisely wherein the seduction lies, who is the agent, who the object. In this case, the child is enjoined to spend much of his young life pursuing the elusive object of his love as she metamorphoses. When he comes upon her at last, hidden inside the body of a goat, he cuts open the goat only to find a cat, and within the cat, a guinea pig, and within the guinea pig, a white dove. The notion that the traditional “objects of study” regularly assent to a passive, one way correspondence is erroneous. They may steadily retreat before one, coyly or in earnest. A subset of society has its own motives for be coming permeable, and even when it consents, it may set precise lim its on the integration and penetration it allows—this far and no fur ther. A populace may have reasons, and not necessarily naive ones either, for not only consenting to, but even soliciting the presence of an outsider. My first experience with the village of San Jeronimo came about when three of its prominent citizens invited me there, after happen ing upon me and asking me to translate into English a phone call to Los Angeles regarding the purchase of some buses for a transport co operative they wished to inaugurate. In search of a greater autonomy, they availed themselves of the services of a forastero. That word, bor rowed from Spanish, is a multivalent and ambiguous term used by Quechuas to refer to outsiders. It translates as “foreigner,” outsider,” “interloper,” but also as “sojourner” and “pilgrim.” It is difficult to pre dict, on any given occasion, its exact connotations. To thank me for my help, the San Jeronimians invited me to participate in a strenuous rit ual hike around the borders of their community, where we drank cane liquor from a flute, and they piled stones along the boundaries of their lands to mark out what they owned, on account of past disputes with neighboring indigenous communities. A few weeks later they confessed to me that on the day of the hike, they’d brought along a first-aid kit because they assumed I would pass out at some point during the walk. A certain form of machismo—the ability to tough it out—is highly regarded in the Southern Andes, and although I hadn’t known about the first-aid kit, I realized at the very moment I was climbing those hills that I was being put to a test of man hood, egged on by men who had an amused and lively expectation of my failure. When 1 didn’t succumb to exhaustion, they were nonethe less pleased, but now in a different way, one that seemed to ask for a continuation of our relationship. Miguel Waman, one of the peasant farmers who I would come to know extremely well, tells just such a story. The daughter of the ha cienda owner, after her father dies, announces that she’ll marry the man who accompanies her no matter where she goes. “Wherever I go, you must follow me.. .Whatever I eat, we’ll eat together.” Two rich suit ors accept her offer, and she takes them one by one to the graveyard at the edge of town. When she’s on the point of opening the gate to the graveyard, each of the suitors runs away screaming. Finally, the poor son of the hacienda caretaker takes her up on her dare, and stays be side her while she opens the gate with her key. Creeeak! It opened. He was at her side, and didn’t let go of her. That little tiny key was right in her purse, that little bitty key was the key to the niche, just small. And with dial, she opened the little iron gate covering the funerary niche. After she opened it, she pulled out a big platter of roast lamb. That’s what she took out. Crack! She gave the young man a big old chunk of it, right into his hands. He took the whole thing right into his hands. The girl began to eat. The boy also ate his fill with gusto. Because, well, it was good meat, lamb. In the morning, they went back to the village. Right away, they married. Miguel Waman ends the tale by saying that through trials like those “That’s how you find out about a man’s weakness.” After the hike, the men invited my wife and me to eat succulent roast guinea pig, a delicacy in Andean cooking, along with corn on the cob, goat cheese, stuffed red hot chili peppers, bread, and potatoes in pea nut sauce. As we sat among them at a long table, plates heaped with food and warm, spicy liqueurs, home brewed, being plentifully served, the liquor hummed in my head, freeing up a tongue that had gotten tied by the constant, abstract study of the Quechua language. I might, at that moment, if I’d known Miguel’s tale, have nursed the ephemeral, drunken, and false feeling of being the boy who won the hacienda owner’s daughter by dint of his perseverance. But I had yet to collect even my first folk tale. Within a short time, I had moved into that village, San Jeronimo, to partake of a reality that turned out to be less heroic, and more mo notonous than the kinds of intoxicated fantasies permitted within folk tales. I spent several weeks just hanging out. I helped some of the vil lage’s Indians dig wells and plant corn. I drank horrible, rancid chicha. 3 I paid black market prices to the crafty corner merchant to buy my daily newspaper-rolled packet of oatmeal, and most of all 1 waited, with oblig atory patience, for circumstances to conspire so that I could collect on cassette tape my first folk tale, or even a measly riddle. Many people treated Miriam and me with courtesy, even with warmth, but the folk- loristic occasion I awaited continued to evade me. I caught cold every two weeks from bathing in the freezing water of a garden hose, which made steam form around my shivering body like the numina that were supposed to leap from the mouths of those unlucky people who hap pened upon wandering condemned souls on mountain paths. I began to realize why the Quechua Indians divided their diseases into hot ones and cold ones. When I wasn’t in bed with a cold, I accompanied the subsistence farmers out to their acreage, watched them, and once in a while joined in their labors. To tell the truth, I wasn’t much real help during the sojourns in the fields, but they allowed me to offer those symbolic gestures as evidence of my ineptitude in questions of agri culture, and of my goodwill in questions of friendship. They teased me ferociously, in a Quechua dialect that I still only hallway understood. They asked, when they saw me cooking and hand washing my clothes in a rented room, whether maybe I hadn’t eaten too many sweets as a child. The women were just as intractable on this point as the men. When they found out that my wife and I didn’t have children, they took to referring to her in half-serious jest as mula—a mule, that hybrid animal that can’t produce offspring, and one of the gravest insults that can be laid upon a woman in Quechua culture. Ru mors circulated that we were cocaine heads, the kind one always saw hanging out on Procuradores Street in Cusco, because after all, nobody could figure out where the money came from that we lived off of, and the words “grant” or “scholarship” didn’t have any convincing mean ing for them. The peasant farmers looked down on the so-called “in ternational hippies” of Gringo Street with the strongest possible dis dain, and just as I couldn’t help clinging to vestiges of my preconceptions about them, they, for their part, couldn’t give up com pletely the folklorisms in their attitude toward me. Several of them re mained convinced that I possessed secret riches, and once, several of them visited me to propose a joint venture that had something to do with a metal detector. In that scheme, they had themselves marked out as the brains, and me marked out as the venture capitalist. Even after the ritual hike, despite Miriam’s and my warm reception, and despite general agreement among our dinner hosts that our liv 4