Sex, love, and letters : writing Simone de Beauvoir PDF

Preview Sex, love, and letters : writing Simone de Beauvoir

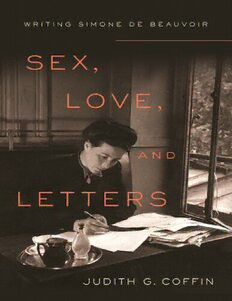

Sex, Love, and Letters Writing Simone de Beauvoir Judith G. Coffin Cornell University Press Ithaca and London To the memory of Vi and Ned Coffin, Margot Coffin Lindsay, and Bill Coffin Contents Acknowledgments A Note on Translations and Abbreviations Introduction 1. The Intimate Life of the Nation: Reading The Second Sex in 1949 2. Beauvoir, Kinsey, and Midcentury Sex 3. Readers and Writers 4. The Algerian War and the Scandal of Torture 5. Shame as Political Feeling 6. Second Takes on The Second Sex 7. Couple Troubles 8. Sexual Politics and Feminism Conclusion Notes Archival Sources Index Acknowledgments This book turned out to be harder to write than my first exhilarating encounter with the archive of readers’ letters to Simone de Beauvoir suggested. It is a pleasure to thank the colleagues, friends, and institutions that have been helpful for so many years. My first debt of gratitude is to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and especially the late, beloved Judith Vishniac, for getting this project launched. Ellen Fitzpatrick, Helen and Dan Horowitz, Susan Faludi, and Russ Rymer, my colleagues during that year at Radcliffe kept it going. I am grateful to Alan Tully and Jacqueline Jones, chairs of the history department at UT Austin, who allowed me to take leave when the chances arrived, and to the Institute of Historical Studies at UT, which provided an internal fellowship. Special thanks to Nancy Cott for her support, expert advice, warmth, and friendship for so many years. Along the way, any number of friends and colleagues have provided a critique, comment, or insight that landed at just the right moment. Those include Darcy Vebber and Andy Romanoff; Hervé Picherit, Evan Carton, and Alex Wettlaufer; Leora Auslander and Thomas Holt; Tamara Chaplin, Herrick Chapman, Indrani Chatterjee, Carolyn Eastman, Seth Koven, Sheryl Kroen, Lisa Leff, Philippa Levine, John Merriman, Mark Meyers, Mark Micale, Lou Roberts, Marine Rouch, Joan Scott, Todd Shepard, Judith Surkis, and Jim Sidbury. They may not recognize their contributions, but I vividly remember each of them. Sandrine Sanos and Dan Sherman have endured sporadic barrages of questions from me, and they have responded with the kind of patience and humor one usually gets only from family. Thanks to them for being such good friends. I am especially grateful to the Friday afternoon writing group: Tracie Matysik, who has been its organizer, Ben Brower, Yoav Di-Capua, Sabine Hake, and Joan Neuberger. All are perceptive readers, ace editors, and excellent friends. Samantha Pinto was a font of energy and good ideas during the last year of writing. I count myself lucky to have had gifted students, now colleagues, who helped with archival research and references, visual materials, computer glitches, or tricky concepts: Katie Anania, Matthew Bunn, Elizabeth Garver, Sarah Le Pichon, Mary Katherine Matalon, Michael Schmidt, and Evan Spritzer. It is hard to imagine the final stages of putting the book together without the blazingly efficient and indomitable Amy Vidor. Thanks to Alice Kaplan, Emma Kuby, and Sharon Marcus, formerly anonymous, outside readers for Cornell University Press, who took time away from their lives and work to give such generous comments on the draft of the manuscript. Emily Andrew understood this project right away, perhaps because she is such a wonderful reader and appreciates what readers can bring to writers. It has been a pleasure to work with her and the whole team at Cornell University Press. A generous subvention grant from the Office of the President at the University of Texas at Austin has helped to defray the cost of publication. It has become commonplace to photograph hundreds of documents in archives and work on them at home. The letters on which this book is based cannot be reproduced in any form. That has meant spending many summers working in Paris, which, as my fellow French historians know, is not always as glamorous as it sounds. I am grateful to the curators in the manuscripts division at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Mauricette Berne and Anne Mary, who helped with the archive, even as it was barely catalogued. Above all, I am very grateful for the time I have had with my long-standing friends and their families. Over many years, they have supplied nearly boundless camaraderie, festive meals, comfortable beds, historical information, and research clues. The late Dr. Cécile Goldet gave me an inside look at the life of an ob/gyn during the 1950s and 1960s, setting up clinics and smuggling contraceptives into France. Catherine Fermand, Jean- Philippe Pfertzel, and Julia Pfertzel, Martine Méjean and Pierre Goldet, Kattalin and Jean-Michel Gabriel, and Joel Dyon and Lydia Zerbib—thank you all for everything. I am at a loss for words that will adequately thank Willy Forbath. He has read every part of this book, and some parts many times. Any phrase that seems well-turned or any particularly precise formulation probably bears his mark. His perceptiveness on so many subjects is matched only by his patience, enthusiasm for others’ ideas, and wry wisdom in everyday matters. He has made this book better in every way, and the same goes for my life. Zoey and Aaron Forbath will attest to that, but they also deserve their own thanks for being such reliably good kids and, now, warm, funny, and smart adults. Thanks to Haley Perkins, Tom Langer, and, most recently, Henry Forbath Langer for bringing such joy to the family. In the name of generational continuity, I dedicate this book to the memory of my parents, Ned and Vi Coffin, my aunt Margot Coffin Lindsay, and my uncle Bill Coffin. They had high standards, and they were good writers. They liked what they read of this book, and though it is too late to tell them, that meant the world to me. A Note on Translations and Abbreviations Translations of the letters are my own. So are the translations from the memoirs. The volumes are abbreviated as follows: JFR: Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée (Gallimard, 1958), in English, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter FA: La force de l’âge (Gallimard, 1960), in English, The Prime of Life FC: La force des choses, 2 vols. (Gallimard, 1963), in English, The Force of Circumstance TCF: Tout compte fait (Gallimard, 1972), in English, All Said and Done For The Second Sex, I have tacked between the 1953 translation by H. M. Parshley (Vintage edition, Random House, 1989) and the 2009 translation by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (Knopf, 2009), TSS 1953 and TSS 2009, respectively. I have provided page numbers for both translations and for the French editions DS1 and DS2. Both English translations have been assailed, and the stakes of those debates are high, or at least bound up in the philosophical understanding of Beauvoir. Fortunately, the most important contributions to this debate have now been gathered up into one volume: Bonnie Mann and Martina Ferrari, eds., On ne naît pas femme, on le devient: The Life of a Sentence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). See especially section two and the articles by Margaret Simons, Toril Moi, Nancy Bauer, and Meryl Altman. Thanks to French Politics, Culture & Society and the American Historical Review for allowing me to use some previously published material: “Historicizing The Second Sex,” French Politics, Culture & Society 25, no. 3 (Winter 2007): 123–48. “Beauvoir, Kinsey, and Mid-Century Sex,” French Politics, Culture & Society 28, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 18–37. “Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir, 1949– 1963,” American Historical Review 115, no. 4 (October 2010): 1061–88.