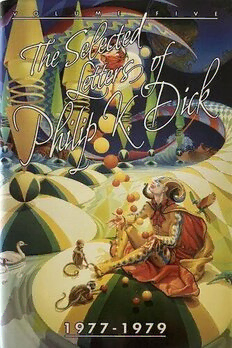

Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick, 1977-1979 PDF

Preview Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick, 1977-1979

1977-1 979 R E T N A P E L O C NI Y B O T O H P 1977-1 979 Edited by Don Herron Introduction by Robert Anton Wilson Underwood-Miller Novato, California Lancaster, Pennsylvania 1993 THE SELECTED LETTERS OF PHILIP K. DICK 1977-79 Trade edition: ISBN 0-88733-120-3 Slipcased edition: ISBN 0-88733-121-1 Copyright © 1992 by The Estate of Philip K. Dick Frontispiece photo of Philip K. Dick © 1980 by Nicole Panter Book design by Underwood-Miller Printed in the United States of America All Rights Reserved “The Death of A Toad” from CEREMONY AND OTHER POEMS, copyright 1950 and renewed 1978 by Richard Wilbur, reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. An Underwood-Miller book by arrangement with The Estate of Philip K. Dick. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without explicit permission from the author or the author’s agent, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages. For information address the publisher: Underwood-Miller, 708 Westover Drive, Lancaster, PA 17601. Caution: These letters are offered for the insight they may provide into their author; they cannot be considered reliable sources of information about any other persons. Special thanks to Allan Kausch for coordinating the preproduction of these volumes. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data (Revised for vol. 5) Dick, Philip K. The selected letters of Philip K. Dick Includes index. Contents: v. [3] 1974. -v. 4.1975-76. -v. 5.1977-79. 1. Dick, Philip K.—Correspondence. 2. Authors, American—20th century—Correspondence. 3. Science Fiction—Authorship. I. Tide PS3554.I3Z48 1991 813’.54 “B” 89-25099 ISBN 0-88733-104-1 (trade ed.: v. 3) ISBN 0-88733-105-X (slipcase ed.: v. 3) ISBN 0-88733-120-3 (trade ed.: v.'5) ISBN 0-88733-121-1 (slipcase ed.: v. 5) Fore-Words: PKD Deconstructed and Reconstructed by Robert Anton Wilson I — “Could you, would you, with a goat7” "Logic!” cried the frog. “There is no logic in this!” This is not a normal world. — Mr. Arkadin — Batman Long ago, when my youth burned green and wild with oats (as Dylan Thomas, or a bad parodist of Dylan Thomas, might write) I picked up a sci-fi magazine and read a very short story called “Roog.” The story described a dog’s “paranoid suspicion” against garbage collectors, told from the dog’s point of v*iew, and it * Philip K. Dick said in an interview once that he conceived “Roog” while watching a dog and trying to figure out how the dog perceived/conceived/constructed his world. I also spend lots of time watching dogs, and other animals, trying to intuit or deduce or guess what sort of feeling and/or thinking they do. Like Finnegan (vide infra, dig?) I have come to the conclusion that humans differ from other animals only in worrying about whether their opinions and behavior can pass a Political Correctness test E.g. I remember once looking at a Kamodo Dragon, on a TV nature documentary, while he ate a crab. The narrator identified this particular Kamodo Dragon as “a male around 50.” As a male around 50 who also liked crab for lunch, I felt an immediate empathy or “oneness” with this weathered veteran of the reptile social order. I thought for a while about how much all males around 50 have in common, besides irony. Then, when 1 wondered about the differences between Mr. K. Dragon and myself, I realized that, most obviously, he had never wasted a minute in his whole life wondering if other reptiles would think his behavior Politically Correct or Politically Incorrect I regard that Kamodo Dragon as one of my most blessed Teachers and I hope that, like me, he has reached 61 and still occasionally eats crab for lunch. vj THE SELECTED LETTERS OF PHILIP K. DICK absolutely juiced my neurons. I felt as if I had just smoked my first pipe of Alamout Black hasheesh (“We taking you higher”) all over again. I felt wigged. I felt as if “illuminated from above.” I felt, in short, that the dog had talked to me. Well, that Trip occurred a long time ago—almost forty years ago, I suspect—but I never forgot the name of the author of “Roog” and I never stopped looking for anything else by him in print. In 1978 or ’79 I finally met him—Philip K. Dick in all his beamish and batty beatitude. We both had reached our mid-forties by then, and I think we shared the subterranean tremors that shift male tectonic plates at that age. Specifically, as writers concerned with the “abnormal,” we each wondered sometimes if we had absent-mindedly graduated, somewhere along the line, from whimsy to lunacy. Phil had the persistent notion that, in February 1974, he had made contact with some sort of Higher Intelligence. Of course, as a card-carrying Postmodernist, he never really believed that totally. I had the suspicion that I had also contacted a Higher Intelligence, in July 1973.*Of course, as an initiated Deconstructionist, I also never believed that totally. I think most of my first conversation with Phil revolved, like some huge model of a clock or the Newtonian universe, around one blazing center: his attempt, within the rules of courtesy, to test me and determine how crazy he should consider me. If he could pronounce me sane, I felt, he would feel more secure in accepting the same verdict on his own condition. I think Phil classified me as relatively sane (like most writers) and that helped him, for that day, to accept himself also as no wackier than the rest of our profession. Of course, if I know anything about Phil Dick, by the next day he probably got around to wondering if the Empire had manufactured a Robot Allegory Wizard and passed it off on him as a writer with the same initials, just to confuse him further about the problems of “reality” and “normalcy.” Phil always felt very perplexed about “reality” and “normalcy,” because he couldn’t seem to get a hold of either of them. * Phil’s Contact experiences and mine differed in all respects but two (1) both of us had traditional mystic/pantheistic Visions in part of the Trip, and (2) both of us, oddly, had the impression, at some point, that the communicating “entity” resided in the system of the double star, Sirius. Both of us also subsequently regarded the whole matter with a mixture of excitement at the possibilities opened to us and a high degree of cautious agnosticism about accepting any one explanation of the phenomenon. As Finnegan wrote (Golden Hours, IV, 73), “One must read David Hume extensively, ingest the ‘magick herb’ of which Abdul Alhazred hints, or speak Gaelic fluently, to escape the Imperialist and dogmatic constraints of English grammar.” I meet two out of three of those requirements. THE SELECTED LETTERS OF PHILIP K. DICK vii Phil reveals in this book (in a letter to John Van der Does, an old friend of mine) that Alfred Jarry’s system of’Pataphysics played a larger role in his thinking and writing than most commentators have noticed. (One who, finishing the last page of Jarry’s Ubu Roi, turns at once to the first page of Phil’s UBIK and reads on, will see the connection at once.) Perhaps Phil’s major perplexities and existential agonies resulted from his failure to read Jarry’s great Irish disciple, Finnegan, whose system of’P*atapsychology rests on the First Noble Truth (also called Murphy’s First Fundamental Finding), “Nobody has ever seen a bloody ‘average’ man or woman; nobody has ever experienced a fucking ‘normal’ day.” (Professor Finnegan actually heard this—in a minor epiphany—from one Sean Murphy of whom nothing else remains on record except for a remark Finnegan attributes to one Nora Dolan: “The only hard work the Murphy lad ever did happened twice a night when he picked himself up from the floor after falling off a bar-stool.”) The Committee for Surrealist Investigation of Claims of the Normal (*C*SICON), of which I have the honor to serve as President and CEO, has conducted numerous scientific experiments upon this matter and we have found thus far no exceptions to Murphy’s First Fundamental Finding. * * * The average and the normal “exist” theoretically (i.e. in a ghosdy way) as mathematical abstractions, but nobody ever encounters them in human life. As Finnegan wrote the day his second great Enlightenment first burst upon him while visiting his friend Dr. Hoffman in Basel (April 19, 1943): “The very act of speaking or writing the Saxon verb ‘is’ strengthens the British Monarchy.” We have titled that the Second Noble Truth, of course. * Usually mis-“corrected” into Parapsychology by well-meaning but ill-educated copy editors. This has resulted in endless polemic against Finnegan by people who haven’t even read his major works. See e.g. Sheissinhosen, Finneganismus und Dummheit, University of Heidelberg, 1982, Werke, Vol. 2, p 230-270, Vol 3 passim and Vol. 7 p 3-989 (1987). A semiotic similar to Finnegan’s appears in Michael Foucault’s L’Archeologie de Savoir, Editions Gallmard, Paris, 1969. * * Which you really must not confuse with CSICOP, an Imperialist cult devoted to vicious and virulent anti-Finnegan propaganda, evidendy provoked by the ubiquitous ’Patapsychology/Parapsychology misprint which haunts all editions of Finnegan’s Golden Hours (Vols I-XXIII) until the epic-making corrected edition of Gobbler (Golden Hours, Royal Sir Myles na gCopaleen Non-Phenomena Institute, Dalkey, 1993.) * * * All data remains in MS. as yet, but the Royal Sir Myles na. gCopaleen Theochemical Institute, Poolbeg, promises to bring forth a collected edition of the best 666 papers by researchers who, seeking everywhere on this planet for “normalcy” or “averageness,” have found no empirical evidence of either. See, in this connection, Studies in Ethnomethodology, Garfinkle, University of California Press, Los Angeles, 1968. viii THE SELECTED LETTERS OF PHILIP K. DICK The Sage of D*alkey (as we in CSICON always call Finnegan) would have loved Phil Dick. Both agreed that “the Empire never ended,” although Phil found evidence of it chiefly in American politics and Finnegan found it in the structure of the neurolinguistic and logical structures the British have imposed on the planet (See, for instance, Finnegan’s Semiotic Analysis of Various Translations of the Necronomicon, Royal Sir Myles na gCopaleen Neuropolitical Institute, 1944, in which de Selby argues that, just as anybody who uses the words “revealed truth” thereby perpetuates what he called “Papist gossip,” * * anybody who uses the words “objective truth” perpetuates “the Empire’s lordly lie of divine impartiality.” This passage, p 69-93, includes the famous bon mot, “Logical Consistency and British Imperialism must have had the same mother, because they look like twins to me.” The O’Brien pronounced this “perhaps the most Gaelic sentence ever written in the English language, and therefore the most subversive sentence also.”) But perhaps I proceed too quickly into the Celtic Twilight Let us, as the more earthy Chinese say, draw our chairs closer to the fire and look more closely at what we have said. Jarry’s ’Pataphysics, begins with the dispassionate study of * Dalkey: a small town on the south of Dublin Bay, so eccentric that as Sir Myles na gCopaleen said, even the streets seem to meet by accident Finnegan lived there during the years of his greatest philosophical and scientific investigations, having left Paris in 1937 after the heartbreak he experienced when Sophie Deneuve, his one great amour, left him to engage in stealthy combat with Gertrude Stein for the hot jungle love of Alice B. Toklas and the secret formula of her wonderful Brownies. Sir Myles never left Dalkey in his life, and boasted of the fact He founded his various Institutes, originally, not to publish Finnegan but to promote his favorite (pre-Finnegan) philosopher, Bishop George Berkeley, who had proven that the universe doesn’t exist but God thinks it does. Sir Myles regarded Berkeley, Finnegan, Jonathan Swift and William Rowan Hamilton as Ireland’s four greatest heroes, because they had undermined the entire Logical Universe upon which British Imperialism rests. (Swift proved, in his dispute with the astrologer, Partridge, that just because a man repeatedly denies that he has recently died, we do not necessarily have to believe him. Hamilton invented quartemions, the mathematics in which, contrary to what they tell us in school, x times y does not equal y times x.) Sir Myles’s four heroes—like Wilde, Shaw, Joyce and Beckett (among others)—all illustrate the typical Irish response to a Logician or an Englishman: which consists of “You claim that’s a proof? Sure, you haven’t considered.... ” and then Logic becomes as full of pot-holes as the streets of Belfast. * * In ’Patapsychology “gossip” signifies any verbal communication with a hidden agenda, and “the instinct to gossip” explains most of what other, pre-Deconstructionist thinkers would variously call “the search for truth” or “the impulse to play” or “the creative spirit” Thus, to Finnegan, the Doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, the theory of Natural Selection, Joyce’s Ulysses, the paintings of Picasso, the Collected Speeches of George Bush, Phil Dick’s Exegesis and even Finnegan’s own writings, all represent “state-specific gossip systems.” Compare Garkinlde and Foucault, op. cit. and Korzybski, Science and Sanity, Institute of General Semantics, 1948. THE SELECTED LETTERS OF PHILIP K. DICK ix non-repeating state-specific events—precisely those “eccentricities” that orthodox science, and even Chaos Theory, seem unable to contemplate—and arrives at a predicament of “baffled suspiciousness” characteristic also of Lacan, Foucault, Fort, Derrida and modern philosophy in general; the same baffled suspiciousness, I might add, that we recognize in the “method” acting of Brando, the stories of Borges, the films of Bunuel and, of course, Philip K. Dick’s ouevre. One should never confuse this Zen-like wariness with paranoia, the quite different state of unbaffled (indeed, dogmatic) suspiciousness. Finnegan’s ’Parapsychology, similarly, begins from the investigation of “preposterous memories”—things we think once happened to us, but still can’t believe—and arrives at a position of astonished agnosticism about all workings of the primate and hominid nervous systems, including the human. (From this foundation Finnegan built his notorious rejection of English grammar, the 24-“ hour” day, the 60-“ minute” hour, the system of “inches, pounds, shillings, yen, dollars, volts, ergs, light-years, nations, ‘laws,’ ‘commandments’ and other tribal gossip,” etc.) Perhaps I can suggest the basic difference (in flavor if not in substance) between Finnegan’s view (and mine) and that of Phil Dick by recounting and revising Phil’s tale (later in this book) about Zebra and the alphabet soup. In the early drafts of VALIS, Phil considered having Zebra—the hypothetical Higher Intelligence that disguises itself from us, like certain insects, by perfectly matching and thereby blending itself into the environment (the whole bloody environment, grok?) —almost tip its hand to one mildly paranoid investigator by spelling out in his alphabet soup: THERE IS NO ZE This message, although (or because) incomplete, creates an Empedoclean Loop. If the investigator believes the implicit message, “There is no Zebra,” he must simultaneously and immediately doubt it, because only Zebra or God—any difference between the two has now vanished—could send precisely that message by precisely that medium. Such self-canceling prophecies fascinated Phil as much as they have also captivated Zeno, Russell, Whitehead, Wittgenstein, Foucault, L*acan, Korzybski, Garfinkle and Hofstadter (to name a few ...) A Finneganoid equivalent (or non-equivalent) occurs if one imagines the alphabet soup spontaneously spelling out COLORLESS GREEN IDEAS SLEEP FURIOUSLY Foucault op. cit. has had some interesting observations on this “sentence” (in his labyrinthine and truly formidable discussion of the impossibility of separating * According to the World Health Organization, approximately 100, 000,000 acts of sexual intercourse occur every day on this planet That averages out to 4, 166, 667 per “hour,” or 69, 450 every “minute. ” I originally decided to mention this as a bonus to those scholarly types who actually read the footnotes, but now that we’ve raised the topic, do you ever worry that somebody else has gotten a lot of your fair share?