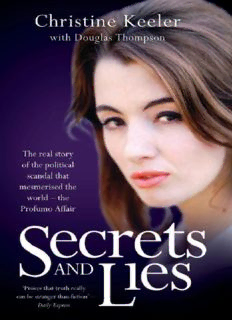

Secrets and lies : the real story of the political scandal that mesmerised the world : the Profumo Affair PDF

Preview Secrets and lies : the real story of the political scandal that mesmerised the world : the Profumo Affair

For Desmond Banks ‘As for Christine Keeler, let no one judge her too harshly. She was not yet twenty-one and since the age of sixteen she has been enmeshed in a net of wickedness.’ Lord Denning, the ‘Denning Report’, September 1963 ‘Christine was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen; she took your breath away. Every man who met her wanted her and those who couldn’t have her wanted to punish her. She was highly decorative, kind and charming. Is what she did really so awful? She was 19, she had no idea what she was getting herself into. They knew what they were doing, and yet Profumo is now regarded as some kind of saint.’ Artist and writer Caroline Coon on Christine Keeler in the 1960s ‘I nostalgised the government by the upper class, which is what I thought it would be – the whole thing really run by the old Etonian mafia – when first I wanted to get in in 1964. Alan Clark, Diaries, 1993 Contents Title Page Dedication ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FOREWORD: LEAVES WITHOUT TREES PROLOGUE: GUNSMOKE 1. NIGHTLIFE 2. FAST TRACKS 3. UPSTAIRS, DOWNSTAIRS 4. HANDS ON 5. UNDRESSING FOR DINNER 6. CHAMPAGNE MODELS 7. TRAITORS’ MEWS 8. BAD LUCK 9. A LONG, HOT SUMMER 10. LOVE LETTERS 11. CORNERED 12. THE SMOKIN’ GUN 13. RABBIT IN THE HEADLINES 14. CRUEL INTENTIONS 15. CONFIDENTIAL AGENT 16. MIDSUMMER MADNESS 17. DANGEROUS DECEPTIONS 18. ROUGH JUSTICE 19. THE TRIALS OF CHRISTINE KEELER 20. LUST AND MARRIAGE 21. TAXING TIMES 22. SUCH A SCANDAL 23. EPILOGUE: HINDSIGHT POSTSCRIPT APPENDIX: THE CHRISTINE KEELER FILES Plates Copyright Acknowledgements Unless otherwise stated, photographs are from the Christine Keeler collection, reproduced by permission of Christine Keeler. Lewis Morley photograph © Lewis Morley Archive/National Portrait Gallery. Foreword: LEAVES WITHOUT TREES ‘I WAS DETERMINED THAT NO BRITISH GOVERNMENT SHOULD BE BROUGHT DOWN BY THE ACTION OF TWO TARTS.’ Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, 1963 Oh, it was a time. High Court judges were performing sexual athletics along The Strand. Government Ministers were spectacularly and inventively at it in the bushes in Hyde Park. And up and down the Thames. With the Archbishop’s favourite vicars. ‘If my services don’t please you, please whip me,’ read the card hanging from the bowed neck of a man, nude but for a black leather mask and a white lacy apron, as he served dinner at an aristocratic party. He became The Man in the Mask but he could have been The Man in the Moon for all the accurate guesses at his identity. Rumour was the trade of the town. There was a miasma of stories: a Cabinet Minister, the son-in-law of Sir Winston Churchill, offered the Government photographs of his penis to prove it wasn’t his distinctive organ a high-born lady was dabbling with. Indeed, it was just some Hollywood johnnie and FBI informant who had her devoted attention and string of pearls jangling. That one was true. Most of the others, the Labour Party kerb-crawling cabal, the cross-dressing Royal, the Horseguards’ capers, the sex orgies on an island in the Thames, in a multi-storey car park, a homosexual ‘Hellfire Club’, a mixed assortment, soft and hard core, of deviant delights, were, perhaps, more inspired suggestions. Yet, in the first place there had to be something to embellish. ‘It still seems like yesterday,’ says Christine Keeler, cocooned in both her clothes and her London apartment, hidden as much as she can from the real and suspected intrusion which has shadowed her for more than fifty years. Yes, it is more than half a century since The Profumo Affair began, like so much which surprises us, by happenstance. Christine Keeler remains as quick- witted as she always was. She’s wiser, of course, for after a lifetime of being told one thing and sold another she is cautious. It’s been like that since she was a toddler. Now, everything in her life is considered before action is taken. Even going out for the cat litter. She’s been photographed off-guard doing just that and demonised for being without make-up on her dramatic cheekbones and somewhat dishevelled, dressed down in jeans and big woolly jumpers, anoraks and cover-up coats. It’s her way of hiding, a camouflage from prurient inquiry. The memory’s perception of her is dressed in carefully draped couture Chanel and gloss. She discarded the glamour for the hope of anonymity but long ago accepted that those yesterdays will never be fully erased. Which is why opening up the chapters of her life is again a torment for her. She insists her upset is incidental to getting the story, getting history, accurate. She is someone who was directly involved in world politics at a tumultuous time and about whom so much has been written and said. For decades stories have fluttered around her with nothing solid to ground them, like leaves without trees. She has always avoided talking in detail about her family, about her difficult upbringing and especially that of her own two sons. Family, where the hurt can usually run, has always been a burden, not a solace. And, ironically, the woman dubbed a ‘sex bomb’ has not for a long, long time found herself able to have any meaningful emotional or sexual relationship. So, this book might seem a rueful undertaking. Strangely, it’s not. There is a great felicity in her attitude today, it’s as if she can finally cast off all the demons. No one can hurt her now. Nothing can, she says, except distortions of the past which she is about to set straight in the pages which follow. A great stepping stone in this, a catharsis to the psychobabble lobby, was the death of John Profumo on 9 March 2006, at the age of 91. Christine was offered great financial incentive to talk about him in the days and weeks following his death but never felt it was appropriate. I can understand her reticence: with Profumo gone, she stands alone among the pivotal people, the players who truly mattered, in the sex and politics and vice versa of scandal against which all others have since been sized up. When Profumo died, Christine believed if she’d spoken then that this particular piece of history would have been parcelled off, finally put away in a box, by an Establishment which she regards as not having changed much since she and Stephen Ward became victims of it. Ward killed himself in the flat of Noel Howard-Jones who was his close friend and a fondly-loved lover of Christine. Howard-Jones, a man of privilege, was so dismayed at how Britain’s Establishment treated his friend and justice he left his home country for good. I met him, a most pleasant man, in 2001 when he returned to London from the privacy of abroad to participate with me in a television documentary. He arrived in the mid-morning, filmed his interviews, shared a pot of coffee and chicken sandwiches, and flew off again that afternoon. ‘If it hadn’t been about telling the truth I’d never have set foot on British soil again. I’m off.’ He echoed the distaste of many about a still greatly misunderstood period and the people punctuating it. Christine, very much an everlasting part of that cultural curriculum, knows the events as only an intimate possibly can. I’ve worked with her at different times over many years on her story and there is one undoubted thing I’ve learned: she will always tell the truth. She says she’s never had the time to do otherwise. She’ll correct but she will not retract, she will not compromise, she is emphatic that she will tell it as it is and was, and with no other spin. There is no reward or threat that will make her detour. She is factually fastidious. She’s clever about modern politics but keeps her thoughts to her very small circle of friends. She loves London and can drive you around avoiding traffic jams and the congestion charge like a Grand Prix veteran. She’s tried living outside the city but it’s always called her back. Still, even in the capital she enjoys solitude and is comfortable with herself. She has full, busy days and her principle concern is the welfare of abandoned animals. (What would Freud make of that?) She is widely read but almost shy with her opinions. Shy might seem a strange word for a woman who remains a sexual icon, the pin-up for the anything-goes Swinging Sixties, and whose winning smile and statuesque figure has decorated and brightened not just a chair from Heals but countless history books of the era. Yet, she has to live with her conversation-stopping name. Cary Grant always complained to us that he couldn’t escape being Cary Grant for his mind remained that of Archibald Leach. That’s who he was when he was off-duty for his weekend chats. With Christine it’s similar; she’ll happily talk away and then suddenly stop – surprised at being so outgoing, concerned that what she’s said might be misconstrued or repeated to others. She has to be reassured her privacy is safe for that’s the one thing she has ferociously clung to like a protective shield. She’s not bitter but, rather, disappointed at not being able to trust easily.

Description: