Scapeland : writing the landscape from Diderot's Salons to the postmodern museum PDF

Preview Scapeland : writing the landscape from Diderot's Salons to the postmodern museum

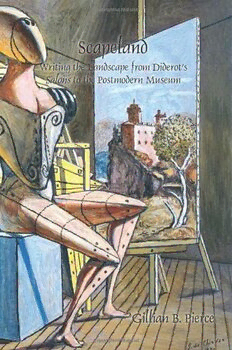

Scapeland FAUX TITRE 383 Etudes de langue et littérature françaises publiées sous la direction de Keith Busby, †M.J. Freeman, Sjef Houppermans et Paul Pelckmans Scapeland Writing the Landscape from Diderot’s Salons to the Postmodern Museum Gillian B. Pierce AMSTERDAM - NEW YORK, NY 2012 Cover Illustration: Giorgio de Chirico, Il contemplatore (1976). © Roma, Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico. The paper on which this book is printed meets the requirements of ‘ISO 9706: 1994, Information and documentation - Paper for documents - Requirements for permanence’. Le papier sur lequel le présent ouvrage est imprimé remplit les prescriptions de ‘ISO 9706: 1994, Information et documentation - Papier pour documents - Prescriptions pour la permanence’. ISBN: 978-90-420-3594-2 E-Book ISBN: 978-94-012-0869-7 © Editions Rodopi B.V., Amsterdam - New York, NY 2012 Printed in The Netherlands Contents Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1: Landscape and the Sublime, 23 or The Art of Nature Chapter 2: Les Limites de l’imitation: 63 Diderot and the Salons Chapter 3: Baudelaire’s Parisian Cityscape: 111 Charles Meryon and Le Spleen de Paris Chapter 4: Mapping the City as Dreamscape: 149 André Breton and le point sublime Chapter 5: “Scapeland”: The Sublime and 193 Lyotard’s Les Immatériaux Conclusion 225 Bibliography 229 List of Illustrations Ch. 2 Gabriel de Saint-Aubain, Le Salon de 1765 (1765). Claude-Joseph Vernet, Le Midi, les baigneuses (1772). Hubert Robert, Vue imaginaire de la Grande Galerie du Louvre en ruines (1796). Ch. 3 Gustave Courbet, L’Atelier de l’artiste (1855). Charles Meryon, Hotel Dieu of Paris Before Its Des- truction (Le Petit Pont) (1850). Le Stryge on a Balustrade of Notre Dame de Paris (photograph from 1915). Ch. 4 Yves Tanguy, Le Palais aux rochers de fenêtres (1942). Reconstruction of the wall of André Breton’s studio on rue Fontaine, Paris (2000). Roberto Matta, Untitled (Personnages transparence) (1941–2). Ch. 5 Marcel Duchamp, Le Grand Verre (1915–23). Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to the many generous col- leagues and friends who have helped shape this work into its current form. James Porter, Timothy Bahti, William Paulson, Ross Chambers, and Santiago Colás all helped guide the project in the earliest stages of its development in the Program in Comparative Literature at the Uni- versity of Michigan. Their critical insights and careful guidance have been invaluable to me over the years. A Rackham Fellowship at the University of Michigan and a summer travel grant from Ashland University gave me time for research and writing when it was most needed. I also received support from my colleagues in the Department of Foreign Languages at Ashland University and in the Division of Rhetoric at Boston University. I thank them all for their thoughtful insights and for always being available for conversations that helped bring new and important perspectives to the work. I also thank the Boston University Center for the Humanities for supporting the project. I am enormously grateful to Paul Pelckmans for his kind encouragement and to the Boston Athenaeum for providing such an agreeable environment for the final stages of writing. Lindsay Guth offered invaluable help with copyediting and proofreading; Bill Pierce applied his considerable editorial experience and skills to the final formatting of the manuscript. Liz Kurtulik at Art Resource, N.Y., helped to facilitate the reproduction of many of the images in the volume. I would also like to thank the Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico in Rome for providing the cover image. Most of all, I would like to thank my family. They have given me time, space, and their unconditional belief in the value of my work. Without their patience and continued faith in the project, it most cer- tainly would not have reached completion. This book is dedicated to them. Introduction The works we admire . . . are ours because we are artists. — André Malraux, Le Musée imaginaire The current study traces a history of art criticism from the eighteenth- century French Salons and Denis Diderot’s art criticism through to the twentieth century, to Jean-François Lyotard’s writing on the sublime and his Pompidou Center exhibition, Les Immatériaux. The work first considers Diderot and his contemporaries in their theories of art, spec- tatorship, and the sublime, and then traces the development of these conceptions through the nineteenth century and Charles Baudelaire’s art-critical writings, through André Breton’s writing on art in Le Sur- réalisme et la peinture and his own personal collection of art on the rue Fontaine, to Lyotard’s postmodern museum. In tracing this literary and critical tradition, it becomes clear that these authors have in common an interest in the ways in which art dematerializes and becomes immaterial, even “non-retinal,” ultimately residing in the individual subjectivity of the viewer and in his or her own projections, imagination, and impulses toward fiction. The idea of the museum itself transforms from the physical spaces of the Salons Diderot and Baudelaire describe to the rotating private collection of Breton—very much his own, personal work of art, perhaps his greatest masterpiece—to Lyotard’s Pompidou Center exhibition, Les Immatériaux, a philosophical experiment in which works are no long- er even visible, but have been dematerialized. Even Diderot was work- ing within a framework of absent paintings in the sense that when he wrote his descriptions of the latest paintings at the Salons for a hand- ful of readers of the Correspondance littéraire, they referred to an ab- 10 Scapeland sent model and thus functioned both as supplements to and replace- ments of the works themselves. As Diderot’s project developed over the years, so did his awareness that without paintings to refer to, his descriptions increasingly became the works for his readers, a real- ization he exploits most fully in his well-known experiment of the Sa- lon de 1767, the famous “Promenade Vernet.” Beginning with Diderot, all the authors in this study explore the subjective aspect of art criticism as perhaps its most valuable element, for that subjectivity represents a form of ownership, whether of virtual pictures, a private collection, or a personal pathway through a museum exhibition as a flâneur, following the dictates of personal whim and fancy.1 Diderot, Baudelaire, Breton, and Lyotard are all fascinated with the figure of the flâneur, and use walking—through a canvas, figuratively, through the city, or through the museum—as a governing trope for their critical work and for the work of the spectator. As Jo- hanne Lamoureux writes in “The Museum Flat,” describing a recent tendency for artists to stage exhibitions at venues throughout the city, rather than in traditional gallery settings, “event specificity is linked with the enhancement of pragmatic habits developed through contact with works . . . requiring the spectator to move—to move literally in space itself, but also to displace the very notion of ‘spectator.’”2 For Lamoureux, the dissipation of the exhibition and its blending into the city itself suggest a shift toward personal itineraries and a more pri- vate, subjective role for the spectator, where “the tableau is ex- changeable not only for money or for another painting: its circulation as an aesthetic value is moreover increased by the fact that it can also be transformed into a garden or a ‘natural’ landscaping experiment, a 1 In her work on human relations to the world of objects in On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Susan Stewart considers the collection (and the museum is a collection on a grand scale) as the ultimate attempt to stage the personality of the collector: “When objects are defined in terms of their use value, they serve as extensions of the body into the environment, but when objects are defined by the collection, such an extension is inverted, serving to subsume the envi- ronment to a scenario of the personal. The ultimate term in the series that marks the collection is the ‘self,’ the articulation of the collector’s own ‘identity’” (Susan Stew- art, On Longing [Durham: Duke University Press, 1993], 162). As Stewart shows, this attempt to domesticate one’s environment is closely linked to the dynamic of the sub- lime. 2 Johanne Lamoureux, “The Museum Flat,” in Bruce Ferguson, Reesa Greenberg, and Sandy Nairne, eds., Thinking about Exhibitions (London: Routledge, 1996), 116.