Revolutionary in Ireland PDF

Preview Revolutionary in Ireland

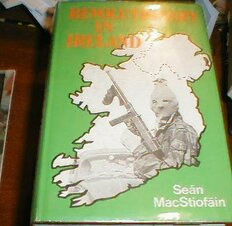

twentieth century revolutionary leader- until ifecently Chief of Staff of the Provisional Irish i Republican Army. It is also a detailed account of i the current ‘troubles’ in Northern Ireland as seen , and experienced by one of the principal figures involved in the tragedy. It is, again, a history of the IRA and the Irish republican movement over a quarter of a century. Sean MacStiofain has been in the forefront of IRA policy making - first as the organization’s Chief of Intelligence and later as its Chief of Staff. It was his responsibility to interpret British policy and to formulate the strategy of his movement. Many have regarded him as a terrorist; others have seen him as a fanatic motivated solely by a thirst for destruction. He, however, regards his twenty-five years in the republican movement as twenty-five years of hard work for the cause in which he deeply believes. Few revolutionary ieaders in this century have recorded precise, detailed accounts of the mannel in which their movements were organized and policy decided. Fewer still have revealed how operations were planned and their personal relations with friends and enemies, with their wives and children. MacStiofain’s guerrilla activities have stemmed from his own interpretation of Irish history and his conviction that Northern Ireland is ’occupied’ territory. Here is his explanation of what he has done and why he did it. No reader can fail to learn from this controversial book - whatever his or her own opinion of ’The Irish Question’. __ Sean MacStiofain, born in east London in 1928, T joined the IRA in 1949. He had previously \ completed his national service in the Royai Air Force, and had become increasingly involved in 1 Irish politics. Arrested during an IRA arms raid in 1 1952, he spent six years in Wormwood Scrubs 1 prison and, on his release, went to Ireland where he dedicated himself to the republican movement. He was eiected to the IRA leadership in 1964, and played an important role until the Provisional IRA broke away. He served as ’Chief of Staff’ of the ’Proves’ until his arrest and imprisonment by the Irish authorities in 1972. His hunger and thirst strike while serving his sentence attracted world-wide attention. iV •>' ' It V toi \ * T* J*. k 4 • H- » ■ •» ^00 Sean !f GORDON CREMONESI N © Sean MacStiofain 1975 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Set by Preface Ltd, Salisbury Printed and bound in Great Britain by R. & R. Clark, Ltd, Edinburgh, Scotland ISBN 0-86033-031-1 Contents Foreword vii 1 In the Dock 1 2 Discoveries 15 3 Commitment 31 4 Wormwood Scrubs 55 5 The Prison Front 73 6 Homecoming 85 7 Chief of Intelligence 99 8 The North Erupts 115 9 The Provisionals 133 10 Facing the Storm 145 11 Stormont Totters 163 12 Time of Torture 179 13 The Tide Turns 205 14 Bloody Sunday and After 225 15 Soundings 253 16 Truce 271 17 Resumption 291 18 Undercover War 311 19 Arrest and Ordeal 337 Index 365 V To revolutionaries everywhere, especially to their womenfolk who share all their hardships VI Foreword A great deal has been written about me by journalists from all over the world, most of whom have never met me, much less interviewed me. A great deal written has been, to say the least, inaccurate and uncomplimentary. Some of it has been just “black” propaganda or character assassination by the British. More has been written in ignorance by foreign journalists unable to check their facts. But the result has been an image of me as a hard-hearted brute unconcerned with loss of human life or the sufferings of the people, a kind of moron obsessed with the use of violence, and a power-crazy maniac determined to maintain his position at all costs. Now, it is true that while in leadership I was firm and strong- willed. But no revolutionary leader can be otherwise if his movement is to make progress. As the world knows, the Provisional Republican movement made fantastic progress from its humble beginning in December 1969 until my arrest three years later. The loss of human life has always grieved me. I was always conscious that every person killed — combatant or not, and no matter who was responsible — was somebody’s son or daughter, somebody’s husband or father or mother or wife. Every person killed meant enormous suffering and loss to a family on one side or another, and everything possible was always done to avoid civilian casualties. No war can be fought without casualties. The entire Republican movement, both rank and file and leadership, did their utmost to confine casualties to com¬ batants. In spite of all the precautions civilians were accidentally killed by the IRA, and we regretted each one of them. But these fatal casualties were only a small proportion of the total civilian deaths. And the British government, as the aggressor in Ireland, is morally Vll and inescapably responsible for all loss of life and bloodshed in this Irish conflict as in previous ones. As for my alleged power lust, it is a fact that I have always been prepared to serve in any position in which I was needed. If at any time during my period in leadership someone better qualified had become available, I would have stepped down, and it would have been my duty to do so. Leading members of revolutionary movements have to be prepared for character assassination just as much as for actual physical assassination. Both weapons are parts of the stock-in-trade of counter-revolutionary agencies. Character assassination was exten¬ sively used against me from 1971 to 1973, while the self- acknowledged former British agent Kenneth Littlejohn has repeatedly stated that he was instructed to kill me. But I have survived to tell my story, my side of events, of how and why I joined the Republican movement. I hope that in doing so I shall have cleared up a lot of the fiction about myself. I joined the Irish revolutionary movement at the age of twenty- one. For twenty-four years I remained an active member, thinking, working, organising from week to week, day in and day out. All my spare time (and a good deal of my employers’ time) went into the movement. It was in fact my entire life. I joined this movement through conviction, the conviction that the only way to free the country I love so much, and the people I admire so much, was by force of arms. I remained in the movement for twenty-four years, the best years of my life, because I never lost that conviction or the sense of purpose which every dedicated revolutionary must have if he or she is to face up to the long, uphill struggle. I still believe that revolutionary violence is the only way for an oppressed people to win their freedom Great nations as well as small ones owe their existence to it. Who thinks that the people of Mozambique or Angola could overthrow the Portuguese colonial system by debate? Or that the blacks of Rhodesia will defeat Ian Smith’s racialists by constitutional means? For these and for all such imprisoned, exploited peoples, there is no reliable route to freedom other than the armed struggle. But in advocating it, I am not motivated by either sectarian or racialist views. I believe that the English people themselves will one day have to use violence to overthrow the system that has brought so much suffering to so many for so long. It is evident that the viii