Regulation of Synaptic Structure by Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase L1 PDF

Preview Regulation of Synaptic Structure by Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase L1

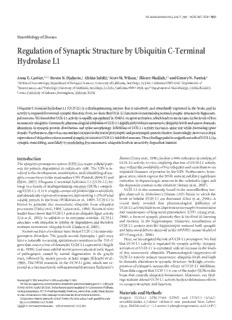

TheJournalofNeuroscience,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868•7857 NeurobiologyofDisease Regulation of Synaptic Structure by Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase L1 AnnaE.Cartier,1,2,3StevanN.Djakovic,1AfshinSalehi,1ScottM.Wilson,4EliezerMasliah,2,3andGentryN.Patrick1 1SectionofNeurobiology,DepartmentofBiologicalSciences,UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego,LaJolla,California92093-0347,Departmentsof 2Neurosciencesand3Pathology,UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego,LaJolla,California92093-0624,and4DepartmentofNeurobiology,CivitanResearch Center,UniversityofAlabama,Birmingham,Alabama35294 UbiquitinC-terminalhydrolaseL1(UCH-L1)isadeubiquitinatingenzymethatisselectivelyandabundantlyexpressedinthebrain,andits activityisrequiredfornormalsynapticfunction.Here,weshowthatUCH-L1functionsinmaintainingnormalsynapticstructureinhippocam- palneurons.WefoundthatUCH-L1activityisrapidlyupregulatedbyNMDAreceptoractivation,whichleadstoanincreaseinthelevelsoffree monomericubiquitin.Conversely,pharmacologicalinhibitionofUCH-L1significantlyreducesmonomericubiquitinlevelsandcausesdramatic alterationsinsynapticproteindistributionandspinemorphology.InhibitionofUCH-L1activityincreasesspinesizewhiledecreasingspine density.Furthermore,thereisaconcomitantincreaseinthesizeofpresynapticandpostsynapticproteinclusters.Interestingly,however,ectopic expressionofubiquitinrestoresnormalsynapticstructureinUCH-L1-inhibitedneurons.ThesefindingspointtoasignificantroleofUCH-L1in synapticremodeling,mostlikelybymodulatingfreemonomericubiquitinlevelsinanactivity-dependentmanner. Introduction disease(Leroyetal.,1998),leadstoa50%reductionincatalyticof Theubiquitinproteasomesystem(UPS)isamajorcellularpath- UCH-L1activityinvitro,implyingthatlossofUCH-L1activity wayforproteindegradationineukaryoticcells.TheUPSisin- mayreducetheavailabilityoffreeubiquitinandcontributetoan volvedinthedevelopment,maintenance,andremodelingofsyn- impairedclearanceofproteinsbytheUPS.Furthermore,trans- apticconnectionsinthemammalianCNS(Patrick,2006;Yiand genicmice,whichexpresstheI93Mmutant,exhibitasignificant Ehlers,2007).UbiquitinC-terminalhydrolaseL1(UCH-L1)be- reductionindopaminergicneuronsinthesubstantianigraand longstoafamilyofdeubiquitinatingenzymes(DUBs)compris- thedopaminecontentinthestriatum(Setsuieetal.,2007). ingUCH-L1–5.Itisahighlyconservedproteinthatisselectively UCH-L1isalsocommonlyfoundintheneurofibrillarytan- andabundantlyexpressedinneurons,representing1–2%oftotal gles observed in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) brains in which the solubleproteininthebrain(Wilkinsonetal.,1989).UCH-L1is levels of soluble UCH-L1 are decreased (Choi et al., 2004). A known to generate free monomeric ubiquitin from ubiquitin recent study revealed that pharmacological inhibition of precursors(Finleyetal.,1989;Larsenetal.,1998).Recentinvitro UCH-L1activityleadstoanimpairmentinsynaptictransmission studieshaveshownthatUCH-L1possessesubiquitinligaseactivity andmaintenanceoflong-termpotentiation(LTP)(Gongetal., (Liuetal.,2002).Inadditiontoitsenzymaticactivities,UCH-L1 2006), a form of synaptic plasticity that is involved in learning associates with ubiquitin to inhibit its degradation and therefore and memory in the hippocampus. Moreover, transduction of maintainmonomericubiquitinlevels(Osakaetal.,2003). UCH-L1 protein into the hippocampus restored both synaptic NumerouslinesofevidencehavelinkedUCH-L1toneurode- andbehavioraldefectsobservedintheAPP/PS1mousemodelof generative disorders. The gracile axonal dystrophy (gad) mice AD(Gongetal.,2006). haveanaturallyoccurring,spontaneousmutationintheUch-l1 Here,weinvestigatedtheroleofUCH-L1atsynapses.Wefind genethatcausesalossofdetectableUCH-L1expression(Saigoh thatUCH-L1activityisregulatedbysynapticactivity.Synaptic etal.,1999).Gadmiceexhibitseveresensoryataxiaatearlystages activationofUCH-L1iscorrelatedwithanincreaseinthelevels of pathogenesis caused by axonal degeneration in the gracile of free monomeric ubiquitin. Pharmacological suppression of tract, followed by motor paresis at later stages (Kikuchi et al., UCH-L1activityreducesmonomericubiquitinlevelsandleads 1990).TheI93MmutationintheUCH-L1gene,whichwasre- todramaticalterationstosynapticstructure.Strikingly,overex- portedinaGermanfamilywithautosomaldominantParkinson’s pressionofubiquitinrescuestheeffectsofUCH-L1inhibition. ThesedatasuggestthatUCH-L1isoneofthemajorDUBsinthe brainthatcontrolsubiquitinhomeostasis.Moreover,ourfind- ReceivedApril15,2009;revisedMay14,2009;acceptedMay15,2009. ingsindicatealteredUCH-L1activityleadstodeleteriouseffects ThisworkwassupportedbyaNationalInstitutesofHealth(NIH)postdoctoraltraininggrant(A.E.C.);NIHGrants onsynapsestructureandfunction. AG18440,AG10435,andAG22074(E.M.);TheRayThomasEdwardsFoundation(G.N.P.);andUniversityofCalifornia, SanDiegostartupfunds(G.N.P.).WethankMariaMoribito,DarwinBerg,AnirvanGhosh,andthePatrickLaboratory MaterialsandMethods foradviceandcriticalreviewofthismanuscript.WealsothankAlanOkadafortechnicalassistance. CorrespondenceshouldbeaddressedtoGentryN.Patrickattheaboveaddress.E-mail:[email protected]. Reagents. UCH-L1 [LDN-57444 (LDN)] and UCH-L3 (4,5,6,7- DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1817-09.2009 tetrachloroindan-1,3-dione) inhibitors were purchased from Calbio- Copyright©2009SocietyforNeuroscience 0270-6474/09/297857-12$15.00/0 chem.NMDAandD((cid:1))-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoicacid(APV) 7858•J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868 Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 (NMDAreceptorantagonist)werepurchasedfromTocrisBioscience. cloned in the pEGFP-N1 vector. The single point mutations in the The hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin probe (HAUb-VME; vinyl UCH-L1DNAwereintroducedbyPCR-basedsite-directedmutagenesis methylesterfunctionalizedprobe)wassynthesizedasdescribedprevi- oftemplateplasmidcDNAusingprimersdesignedtointroducespecific ously(Borodovskyetal.,2002)andwasprovidedbyDr.H.Ovaa(The mutations (C90S, 5(cid:4)-CCATTGGGAATTCCTCTGGCATCGGAC-3(cid:4), NetherlandsCancerInstitute,Amsterdam,TheNetherlands). and D30A, 5(cid:4)-TTCGTGGCCCTGGGGCTG-3(cid:4)). All constructs were UCH-L1-deficientmice.TheUCH-L1-deficientandwild-typelitter- verified by sequencing and by expression of proteins of the expected matemouse(Uch-L1nm3419)brains(8weeksofage)wereobtainedfrom molecularweightinHEK293Tcells. Dr.ScottWilson(UniversityofAlabama,Birmingham,AL).Thisisa Drugtreatmentsandvirusinfections.Forproteinexpressionanalysisby spontaneousmousemutationthataroseatTheJacksonLaboratoryand Westernblottingorimmunofluorescencestainingexperiments,cultured subsequentlymappedbytheScottWilsongroup(Waltersetal.,2008). neuronsweretreatedwith10(cid:1)MUCH-L1(LDN)orUCH-L3inhibitor Antibodies.Thefollowingantibodieswereusedinthisstudy:mouse for24h.InexperimentsinwhichneuronsweresubjectedtoLDNtreat- anti-Myc, rabbit anti-CDK5, rabbit anti-green fluorescent protein mentandinfections,neuronswerefirsttreatedwithLDNandthenin- (GFP),andrabbitanti-guanylatekinase-associatedprotein(GKAP)an- fectedbyaddingvirionsdirectlytotheculturemediumandallowing tibodies (purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti- proteinexpressionfor12–14h.ThetotaltimeofexposuretoLDNwas postsynapticdensity-95(PSD-95)andrabbitanti-GluR1(obtainedfrom keptconstant(24h).Activitystimulationexperimentswereperformed Calbiochem);rabbitanti-Shankantibody(agenerousgiftfromDr.Eu- bytreatingcultureswithNMDAandglycineat50and10(cid:1)M,respec- njoonKim,KoreaAdvancedInstituteofScienceandTechnology,Dae- tively,for10minat37°C.Whereindicated,neuronswerepretreatedwith jeon,Korea);rabbitanti-GluR1,mouseanti-NR1,andrabbitanti-NR2A UCH-L1inhibitor(10(cid:1)M)for24horAPV(50(cid:1)M)for10minbefore antibodies;ratanti-Homerandrabbitanti-SynapsinI(MilliporeBio- additionofNMDA/glycinetotheculturemedia. scienceResearchReagents);mouseanti-Bassoon(NventaBiopharma- Immunostaining.Attheendofeachexperiment,hippocampalneu- ceuticals); chicken anti-Map2 (Abcam); rabbit anti-UCH-L1 (BI- rons plated on coverslips or 35 mm glass-bottom dishes were rinsed OMOL);rabbitanti-ubiquitin(Dako);andrabbitanti-Vamp2(Synaptic brieflyinPBSandfixedwith4%paraformaldehyde(PFA)and4%su- Systems). Primaryneuronalcultures.Hippocampalneuroncultureswerepre- croseinPBS-MC(PBSwith1mMMgCl2and0.1CaCl2)for10minat roomtemperature.NeuronswerethenrinsedthreetimeswithPBS-MC pared from postnatal day 1 (P1) or P2 rat hippocampi as previously andsubsequentlyblockedandpermeabilizedwithblockingbuffercon- described(Patricketal.,2003).Briefly,forimmunostainingexperiments, taining2%BSAand0.2%TritonX-100inPBS-MCfor20min.After rathippocampiweredissected,dissociatedbypapaintreatmentandme- rinsing neurons three times with PBS-MC, primary antibodies were chanicaltrituration,andplatedatmediumdensity(45,000cells/cm2)on addedinblockingbufferandcultureswereincubatedovernightat4°C. poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips (12 mm in diameter) or glass-bottom Thefollowingantibodiesanddilutionswereusedforimmunofluores- dishes (MatTek; 35 mm). For biochemical experiments, mixed hip- cencestainings:mouseanti-PSD-95(1:500),rabbitanti-SynapsinI(1: pocampalandcorticalneuronswereplatedathighdensityonsix-well 2000),mouseanti-Bassoon(1:2000),rabbitanti-Shank(1:2000),rabbit plates((cid:2)500,000cellsperwell)coatedwithpoly-D-lysine.Cultureswere anti-GluR1 (1:20), chicken anti-Map2 (1:5000), and mouse anti-Myc maintainedinB27supplementedNeurobasalmedia(Invitrogen)until (1:1000).AfterthreewasheswithPBS-MC,neuronswereincubatedin 14–21dinvitro(DIV). goatanti-rabbit,-mouse,or-chickensecondaryantibodiesconjugatedto FractionationsandDUBlabelingassay.Fractionsfromratbrainswere Alexa 488, Alexa 568, or Alexa 678 (1:500 each; Invitrogen) at room preparedaspreviouslydescribed(Carlinetal.,1980;Choetal.,1992). TheDUBactivityassaywasdonebyincubating20(cid:1)goflysatesfrom temperaturefor1h.NeuronswerewashedthreetimeswithPBS-MCand mountedonslideswithAquaPoly/Mount(Polysciences).Forlivelabel- neuronalculturesorratbrainfractionswiththeHAUb-VMEsubstratein ingofsurfaceGluR1,theanti-GluR1antibodyagainsttheNterminus labelingbuffer(50mMTris,pH7.4,5mMMgCl2,250mMsucrose,1mM extracellular epitope of the receptor was added to neurons in culture DTT,and1mMATP)for1hat37°C.Proteinswerethenresolvedby mediumat1:20dilutionfor10minbeforewashingoutexcessantibody SDS-PAGE4–20%gradientgels,andblotsweresubsequentlyprobed andfixingwith4%PFA/4%sucrose. with anti-HA monoclonal antibody. Labeled proteins were identified Electronmicroscopy.Maturehippocampalneurons((cid:5)21DIV)were basedontheirmigrationonSDS-PAGEgels,andbycomparisonwith platedin35mmglass-bottomdishesandtreatedwithDMSO(control) previouslypublisheddatainwhichthespecificbandswereanalyzedby massspectroscopy(Borodovskyetal.,2002). orLDN(10(cid:1)M).After24h,cellswerefixedin2%paraformaldehydeand 1%glutaraldehyde,andthenfixedinosmiumtetraoxideandembedded RecombinantDNAandSindbisconstructs.TheSindbisenhancedgreen inEponAraldite.Oncetheresinhardened,blockswiththecellswere fluorescent protein (EGFP) viral construct was made by cloning the detachedfromeachdishandmountedforsectioningwithanultramic- EGFP(Clontech)openreadingframedirectlyintopSinRep5(Invitro- gen).GFPu(inpEGFP-C1plasmidbackbone;Clontech),afusionofthe rotome(Leica).Gridswerestainedwith1%uranylacetateandanalyzed CL1degron(degradationsignal)ontheCterminusofGFP,waskindly withaZeissOM10electronmicroscopeaspreviouslydescribed(Rock- providedbyDr.RonKopito(StanfordUniversity,PaloAlto,CA).GFPu ensteinetal.,2001).Manualanalysisofpresynapticterminaldiameter, isubiquitinatedandspecificallydegradedbytheUPS(Gilonetal.,1998; vesiclenumber,andsynapticcontactzonewasperformed.Atotalof10 Benceetal.,2001,2005).TheAgeI–BsrGIfragmentfromphotoactivat- micrographswasobtainedandfromeachgrid(ninegridspercondition) able(pa)GFP(akindgiftprovidedbyJenniferLipponcott-Schwartz, foratotalof90electronmicrographsanalyzedpercondition.Analysis National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was subcloned into the wasperformedusingImageQuant.Magnificationwas30,000(cid:6).Statisti- GFPuplasmid.paGFPuwasthensubclonedintopSinRep5(Invitrogen). calsignificancewasdeterminedbyunpairedtwo-tailedStudent’sttest. Orientationwasverifiedbyrestrictiondigestandconstructswerecon- LiveimagingofpaGFPudegradation.Culturedhippocampalneurons firmedbyDNAsequencing.TheHis6-Myc-ubiquitinwasprovidedby ((cid:5)21DIV)on35mmglass-bottomdisheswereincubatedfor24hbefore Dr.RonKopitoandwasclonedintopSinRep5.Theyellowfluorescent imaginginmediacontainingeitherDMSO(control)orLDN(10(cid:1)M). protein(YFP)-actinpSinRep5plasmidswaskindlyprovidedbyDr.E. paGFPuvirionswereaddeddirectlytoculturemediaafter12hofLDN Schuman(CaliforniaInstituteofTechnology,Pasadena,CA).Forpro- treatmentandproteinexpressionwasallowedtocontinuefor12–14h. ductionofrecombinantSindbisvirions,RNAwastranscribedusingthe CulturemediawasthenreplacedwithwarmHBS[HEPES-bufferedsa- SP6mMessagemMachineKit(Ambion)andelectroporatedintoBHK linesolutioncontainingthefollowing(inmM):119NaCl,5KCl,2CaCl2, cellsusingaBTXECM600at220V,129(cid:3),and1050(cid:1)F.Virionswere 2MgCl ,30glucose,10HEPES].Cellsweremaintainedat(cid:2)35°Cusing 2 collected after 24–32 h and stored at (cid:1)80°C until use. For UCH-L1 aceramicheatlamp(ZooMed),andbathtemperaturewascontinually expressionconstructs,theUCH-L1openreadingframewasobtained monitoredbyadigitalprobethermometer.Infectedneurons(identified fromIncytefull-lengthhumancDNAclone(OpenBiosystems)encoding bymCherryexpression)werethenphotoactivatedfor10–15swith100 wild-typeUCH-L1andwasamplifiedbyPCRwitha5(cid:4)-oligocontaining W Hg2(cid:7) lamp and a D405/40(cid:6) with 440 DCLP dichroic filter set anXhoIsiteanda3(cid:4)-oligocontaininganAgeIsite,andsubsequently (Chroma).Forliveimaging,pyramidal-likeneuronswereselectedina Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868•7859 microplate fluorometer (HTS 7000 Plus; PerkinElmer) every 5 min for 2 h at room temperature. Westernblotanalysis.Culturedneuronswere lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA)lysisbuffer(50mMTris,pH7.4,150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA)containingproteaseinhibitors(Roche). Rat or mouse brains were homogenized in RIPAbufferat900rpminTeflon-glasshomog- enizers.Neuronalcelllysatesorbrainhomoge- nateswerecentrifugedat14,000rpm,andsu- pernatants were removed and protein concentrationwasdeterminedbyBSAprotein assaykit(Pierce)usingbovineserumalbumin asastandard.Proteinsampleswereresolvedby SDS-PAGEandelectrophoreticallytransferred tonitrocellulosemembranes.Membraneswere thenblockedfor1hinTBSTblockingbuffer (TBS,0.1%Tween20,and5%milk)atroom temperatureandthenincubatedwithprimary antibodiesinblockingbufferovernightat4°C. Theantibodiesusedwereatthefollowingdilu- tions:mouseanti-PSD-95(1:5000),rabbitanti- Synapsin I (1:10,000), rabbit anti-GluR1 (1:5000), rabbit anti-Shank (1:10,000), rabbit anti-GFP (1:10,000), rabbit anti-UCH-L1 (1:5000),rabbitanti-GKAP(1:2000),ratanti- Homer (1:2000), mouse anti-NR1 (1:2000), rabbit anti-NR2A (1:2000), rabbit anti- ubiquitin (1:2000), rabbit anti-Vamp2 (1:5000), and rabbit anti-CDK5 (1:10,000). Blots were then washed three times in TBST washingbuffer(TBS,0.1%Tween20)andin- cubatedwithgoatanti-rabbit,-mouse,or-rat IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1: 5000).Proteinbandswerevisualizedbychemi- luminescenceplusreagent(PerkinElmer)and weredigitizedandquantifiedusingNIHImageJ software.Forstatisticalanalysis,unpairedStu- dent’s t test was performed between any two conditions. Imageacquisitionandquantification.Confo- Figure1. UCH-L1expressionandactivitylevelsinratbrainandmatureculturedhippocampalneurons.A,Representative cal images were acquired using a Leica imageofahippocampalneuronimmunolabeledwithanti-PSD-95andanti-UCH-L1antibodies.B,GFP-expressinghippocampal DMI6000invertedmicroscopeoutfittedwitha neuronsimmunostainedwithanti-PSD-95andanti-UCH-L1antibodies.ThestraighteneddendritesinAandBcorrespondtothe Yokogawaspinningdiskconfocalhead,anOrca regionsindicatedbyarrowsinthewhole-cellimages.ThearrowheadsindicateselectedregionsinwhichUCH-L1colocalizeswith ER high-resolution black-and-white cooled PSD-95andGFP-filledspines.Representativemaximumz-projectedconfocalimages(cellandstraighteneddendrites)aredepicted. CCD camera (6.45 (cid:1)m/pixel at 1(cid:6)) Whole-cellscalebar,20(cid:1)m;dendritescalebar,5(cid:1)m.C,ActiveDUBprofilingwithHAUb-VMEinsubcellularfractionsofratbrain.The (Hamamatsu),PlanApochromat40(cid:6)/1.25nu- immunoblotwasprobedwithanti-HAantibodytodetectactiveDUBs.D,Comparisonoflabeled(active)andunlabeled(inactive)UCH-L1 mericalaperture(NA)and63(cid:6)/1.4NAobjec- (HAUb-UCH-L1andUCH-L1,respectively)inratbrainfractionsinanimmunoblotthatwasprobedwithanti-UCH-L1antibody.E,The tive,andaMellesGriotargon/krypton100mW postsynapticmarker,PSD-95,wasusedascontrolforfractionation.Numberscorrespondtothefollowingfractions:(1)whole-brain air-cooled laser for 488/568/647 nm excita- homogenate(H);(2)crudesynaptosomalfraction(P2);(3)cytosolpluslightmembranes(S2);(4)lightmembranes(Golgi,ER)(P3);(5) tions.Exposuretimeswereheldconstantdur- cytosolicfraction(S3);(6)PSD-1T(oneTritonX-100extraction);(7)PSD-2T(twoTritonX-100extraction). ing acquisition of all images for each experi- ment. Pyramidal-like cells were chosen in a randommanner.Confocalz-stackimages(with0.5(cid:1)msections)were randommanner.Confocalz-stacksweretaken acquiredwitha63(cid:6)objectiveevery2min. at0.4–0.5(cid:1)mdepthintervalsinallexperiments.Forimageanalysis, Invitroproteasomeactivityassay.Proteasomeactivitywasmeasuredas maximum z-projections were used. Images were thresholded equally previouslydescribedwithslightmodifications(KisselevandGoldberg, 1.5–2timesabovebackground.Dendritesfromindividualneuronswere 2005).Briefly,culturedneuronswereincubatedfor24hinmediacon- thenstraightenedandusedforanalysis.Fluorescenceintensityassociated taining either DMSO (control) or LDN (10 (cid:1)M). Neurons were then withpresynapticandpostsynapticproteinpunctawasmeasuredtode- lysed in proteasome assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM terminethesizeandnumberofpuncta(normalizedtodendriticlength) sucrose,5mMMgCl2,0.5mMEDTA,2mMATP,1mMDTT,and0.025% incontrolandLDN-treatedneurons.GFP-expressinghippocampalneu- digitonin)for15minonice.Lysateswereclearedbycentrifugationat ronswereusedforspinemorphologyanalysisusingtheEdgefitterNIH 14,000rpmfor15min.Onehundredmicromolarfluorogenicprotea- ImageJplug-in(GhoshLaboratory,UniversityofCalifornia,SanDiego, some peptide substrate N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amido-4- LaJolla,CA).Todeterminethelengthofaspine,thedistancefromthetip methylcoumarin(Suc-LLVY-AMC)(BIOMOLInternational)wasthen oftheprotrusiontothedendriticshaftwasmeasuredmanually.Tomea- addedtoequalamountsofclearedlysatesina96-wellmicrotiterplate. surethewidthofaspine,themaximallengthofthespineheadperpen- Fluorescence(380nmexcitation;460nmemission)wasmonitoredona diculartothelongaxisofthespineneckwasmeasured.Thenumberof 7860•J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868 Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 spinesvisiblealongthedendritewascounted manuallyper1(cid:1)mdendriticlength.Measure- ments were then automatically logged from NIH ImageJ into Microsoft Excel. Statistical significancewasdeterminedbyunpairedtwo- tailedStudent’sttest.Allimagingandanalysis of ubiquitin rescue experiments (see Fig. 8) wereperformedinablindedmanner.Forquan- tificationoftheproteasomereporterdegrada- tion, images were thresholded above back- ground equally between conditions. Total integratedfluorescenceintensitywasmeasured from dendrites at each time interval and ex- pressedasthepercentagechangefromtime0. Groupedanalysisofdendriticfluorescencede- cayovertimefromeachtreatmentgroupwas plottedaslinegraphs(mean(cid:8)SEM).Thedeg- radationrateofreporterfluorescencedecaywas obtainedbytakingthedifferenceoftotalfluo- rescenceloss[arbitraryunits(AU)]overtime (F (cid:1)F /time )fromindividualexperiments. i n n Themeanrate(cid:8)SEMpertreatedgroupwas thennormalizedtothecontrolrates.Forstatis- ticalanalysis,groupeddegradationrateswere analyzed by unpaired two-tailed t tests. One- halfofthepaGFPureporterdegradationexper- iments were performed in a blinded manner. Therewasnosignificantdifferencebetweenex- periments performed blind and unblind, and thereforethedatawerecombined. Results CharacterizationofUCH-L1 distributionandactivityinneurons To determine the subcellular localization of UCH-L1, cultured hippocampal neu- ronswereimmunostainedforendogenous UCH-L1 and the postsynaptic marker PSD-95(Fig.1A,B).Insomeexperiments, GFP was used as a cell-filling marker to Figure2. Activity-dependentupregulationoffreemonomericubiquitinlevelsinneuronsisdependentonUCH-L1activity. visualizespines(Fig.1B).UCH-L1expres- A–C,Culturedneuronsweretreatedwith50(cid:1)MNMDA/10(cid:1)Mglycineor50(cid:1)MNMDA/10(cid:1)Mglycineplus50(cid:1)MAPVfor10min. sionwasdetectedinbothsomaandden- LysatesfromcontrolandtreatedneuronswerelabeledwithHAUb-VMEsubstrateandsubjectedtoWesternblotanalysis.A,A drites of hippocampal neurons. UCH-L1 representativeimmunoblotprobedwithanti-HAantibodydemonstratesthelevelsoflabeled(active)UCH-L1incontroland isdistributedinamicropunctatemanner treatedneuronsinthepresenceorabsenceoftheDUBlabelingreagent(toppanel).Theblotwassubsequentlystrippedand reprobedwithanti-UCH-L1antibodytodemonstratethelevelsoflabeledandunlabeledUCH-L1(HAUb-UCH-L1andUCH-L1, andpartiallycolocalizedwithPSD-95(Fig. respectively)(bottompanel).B,Arepresentativeimmunoblotprobedwithanti-HAantibodydemonstratesactivitylevelsof 1A,B).Moreover,UCH-L1wasfoundto UCH-L1inresponsetodrugtreatments(toppanel).ThebottompanelofBshowsequalamountsofUCH-L1betweentreatments. belocalizedtodendriticspinesofneurons C,DensitometryanalysisofsixindependentexperimentsfromDublabelingassaysisshown.D–F,Culturedneuronsweretreated (Fig.1B).Tofurthercharacterizethesub- with50(cid:1)MNMDA/10(cid:1)Mglycinefor10min(D)or10(cid:1)MUCH-L1inhibitor(LDN)for24hwithorwithoutanadditional10min cellulardistributionofUCH-L1,weused treatmentwith50(cid:1)MNMDA/10(cid:1)Mglycine(E,F),respectively.Lysateswereresolvedon15%SDS-PAGEandimmunoblotswere differentialanddensitygradientcentrifu- probedwithanti-ubiquitinantibody.Representativeblotsfromeachexperimentareshown.Relativebandintensitiesofcorre- gationtoenrichforvarioussynapticcom- spondingmonomericubiquitinwerequantifiedandaredepictedinthebottompaneloffigureF.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMoffourto partments from rat brain. In addition, fiveindependentexperimentsareshown.Forstatisticalanalysis,one-wayANOVAwithposthocBonferroni’smultiple-comparison testwasused.*p(cid:9)0.05;**p(cid:9)0.01;***p(cid:9)0.001. we used a novel hemagglutinin-tagged ubiquitin-vinyl methyl ester-derived ac- fractionscomparedwiththeotherDUBsdetectedandispresent tivesite-directedprobe(HAUb-VME)thatcovalentlymodifies inanactiveform.AcomparisonbetweenactiveUCH-L1modi- DUBsincludingUCHs(Borodovskyetal.,2002)toprofileactive fiedbythesubstrate(upperband)andtheunmodified,inactive DUBspresentinthebrain.Thisassayprovidesahighlysensitive approachfordetectingUCH-L1activityasourprobeisspecifi- UCH-L1(lowerband)isdemonstratedinFigure1Dandindi- callytargetedtoUCH-L1whenitisinanactiveform.Usingthis catesthat(cid:2)50%ofUCH-L1ispresentinactiveforminthetotal probe,wemonitoredtheactivityofUCH-L1inlysatesgenerated homogenate (Fig. 1D, lane 1). Interestingly, we found that fromratbrainfractions.TheprofileofactiveDUBspresentin UCH-L1associatedwiththePSDisprimarilyinanactiveform thesevariousratbrainfractionsisshowninFigure1C.Alower (Fig.1D,lanes6,7).ToverifythattheHAUb-VMElabelingof exposureoftheblotpresentedinFigure1Cisgiveninsupple- the DUB at (cid:2)35 kDa is primarily modified UCH-L1 and not mentalFigure1A(availableatwww.jneurosci.orgassupplemen- UCH-L3,weperformedtheDUBlabelingassayonlysatesfrom tal material). As observed, UCH-L1 is highly expressed in all UCH-L1-deficient mice (nm3419) (Walters et al., 2008). Here, Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868•7861 wefoundvirtuallynolabelingofanyotherDUBthatrunsator monoubiquitinlevelsinLDN-treatedneurons(Fig.2E)(con- nearthesamemolecularweightofUCH-L1(supplementalFig. trol, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.11; LDN-treated, 0.59 (cid:8) 0.01). Moreover, the S1B,toppanel,availableatwww.jneurosci.orgassupplemental levelsoffreemonomericubiquitininneuronalculturespre- material). Together, our data demonstrate that UCH-L1 is ex- treated with LDN before NMDA receptor stimulation were pressed ubiquitously in neurons with a subpopulation distrib- reduced to the levels observed in control untreated neurons utedtospinesandpostsynapticdensities. (Fig. 2F) (control, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.02; LDN-treated, 0.64 (cid:8) 0.05; NMDA/Gly-treated, 2.0 (cid:8) 0.13; NMDA/Gly plus LDN- treated,1.04(cid:8)0.08;p(cid:9)0.001,one-wayANOVA).Thissug- NMDAreceptoractivationupregulatesUCH-L1activity geststhatNMDAreceptoractivationinneuronsincreasesfree Arecentstudyhasdemonstratedthatpharmacologicalinhibi- monomeric ubiquitin in an UCH-L1-dependent manner. In tion of UCH-L1 activity by 40% is sufficient to significantly addition, we tested whether LDN affected the ability of attenuate LTP in rat hippocampal slices (Gong et al., 2006). UCH-L1 to bind ubiquitin. We performed in vitro ubiquitin ThissuggeststhatUCH-L1functionmayberequiredforsyn- binding assays with either bacterially expressed glutathione apticplasticityandmayitselfberegulatedbysynapticactivity. S-transferase (GST) or GST-UCH-L1 and ubiquitin. We Indeed,depolarization-dependentCa2(cid:7)influxintosynapto- found that pretreatment of GST-UCH-L1 with LDN greatly somes has been shown to produce a rapid decrease in ubiq- diminished its ability to bind ubiquitin (supplemental Fig. uitinconjugates(Chenetal.,2003).Totestthepossibilitythat S2B,toppanel,availableatwww.jneurosci.orgassupplemen- UCH-L1 might be regulated by synaptic activity, we stimu- tal material). Together, this indicates LDN affects both the lated neuronal cultures (DIV 21) with NMDA receptor ago- catalyticandubiquitinbindingactivitiesofUCH-L1. nist.WefoundthatstimulationofsynapticactivitybyNMDA/ glycinesignificantlyupregulatedUCH-L1activityincultured InhibitionofUCH-L1activityaffectssynaptic neurons(Fig.2A,toppanel).Acomparisonoflabeled(active) proteinclusters and unlabeled (inactive) UCH-L1 in response to NMDA re- Recent electrophysiological studies on gad mice and hip- ceptorstimulationisshowninFigure2A,bottompanel.On pocampal slices treated with LDN have demonstrated that average, the activity of UCH-L1 increased by (cid:2)1.5-fold in UCH-L1 is required for LTP and maintenance of memory responsetoNMDAreceptorstimulation(Fig.2B,C)(control, (Gongetal.,2006;Sakuraietal.,2008).Thebrainsofgadmice 1.0 (cid:8) 0.07; NMDA/Gly, 1.63 (cid:8) 0.16; p (cid:10) 0.003, one-way shownogrossstructuralabnormalities;however,itispossible ANOVA). Moreover, the NMDA-induced upregulation of that discrete alterations in neuronal morphology or synaptic UCH-L1 activity was efficiently blocked by pretreatment of structure occur because of the lack of UCH-L1 activity. To neurons with the NMDA receptor antagonist APV demon- examinethispossibility,wecomparedtheimmunocytochem- strating the specificity of our treatment (Fig. 2B,C). This ical distribution of synaptic proteins in control and LDN- novel and potentially important finding demonstrates that treatedneurons,severalofwhicharetargetsforubiquitination synapticactivitycanmodulatetheactivityofUCH-L1. and degradation by the UPS (Colledge et al., 2003; Ehlers, 2003; Guo and Wang, 2007; Lee et al., 2008). Moreover, the UCH-L1activityisrequiredforNMDA-inducedupregulation postsynapticproteinsweexaminedaremajorcomponentsof offreemonomericubiquitin thePSD,whichisahighlydynamicstructureanditsmolecular MultiplefunctionshavebeenascribedtoUCH-L1invitroand composition and biochemical stability is very responsive to invivo.ItisknownthatUCH-L1canactasaubiquitinhydro- changes in synaptic activity. Furthermore, these activity- laseandgeneratefreeubiquitinspeciesfromprecursorubiq- dependentmolecularchangesareregulatedinpartbytheUPS uitinpolypeptides(Wilkinsonetal.,1989).UCH-L1canalso (Ehlers,2003).Wefoundthatexposureofmaturehippocam- bindtoubiquitinandactasaubiquitinstabilizertopreventits palneuronstoLDNleadstodramaticalterationsinsynaptic degradationbylysosomes(Osakaetal.,2003).Therefore,we structure (Fig. 3). We observed a significant increase in the wereinterestedtodeterminewhetherNMDAreceptorstimu- size of several synaptic protein puncta in LDN-treated neu- lationhadanyeffectonthelevelsoffreemonomericubiquitin ronscomparedwiththoseincontrolneurons.Onaverage,the (alsoreferredtoasmonoubiquitin)andwhetherUCH-L1ac- size of postsynaptic proteins PSD-95, Shank, and surface tivityplayedaroleinmodulatingubiquitinlevelsinresponse GluR1punctaincreasedby77,70,and39%,respectively(Fig. toNDMAreceptoractivation.Wefoundthatstimulationwith 3A–D) (PSD-95 puncta, control, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.03; LDN-treated, NMDA/glycine(10min)increasedfreemonomericubiquitin 1.77(cid:8)0.04;Shankpuncta,control,1.0(cid:8)0.04;LDN-treated, levels approximately twofold in cultured neurons (Fig. 2D) 1.69(cid:8)0.04;surfaceGluR1puncta,control,1.0(cid:8)0.07;LDN- (control, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.11; NMDA, 1.8 (cid:8) 0.14). We next asked treated,1.39(cid:8)0.08).Wealsodetectedanincreaseinthesize whether inhibiting UCH-L1 activity blocks the upregulation ofpresynapticproteinpunctaasmeasuredbyimmunolabel- ofmonoubiquitininNMDAreceptor-stimulatedneurons.To ingforpresynapticnerveterminalswithSynapsinIandBas- assessthis,weusedapreviouslydescribedUCH-L1inhibitor, soon. We found that, on average, there was a 34 and 25% LDN,whichspecificallyinhibitsUCH-L1whilehavingnoef- increaseinthesizeofSynapsinIandBassoonpuncta,respec- fectonotherUCHfamilymembers(Liuetal.,2003;Gonget tively (Fig. 3A,B,D) (Synapsin I puncta, control, 1.0(cid:8) 0.05; al.,2006).TodemonstratetheefficacyofUCH-L1inhibition LDN-treated, 1.34 (cid:8) 0.07; Bassoon puncta, control, 1.0 (cid:8) by LDN, neuronal lysates were preincubated with increasing 0.03; LDN-treated, 1.25 (cid:8) 0.02). Interestingly, we found no amountsofLDNbeforeDUBlabelingassays.Wefoundthat observable difference in the dendritic protein marker MAP2 10 (cid:1)M LDN significantly inhibited UCH-L1 activity in vitro stainingbetweencontrolandLDN-treatedneurons(Fig.3C). (supplemental Fig. S2A, top panel, available at www. This indicates that UCH-L1 inhibition preferentially affects jneurosci.orgassupplementalmaterial).Neuronstreatedwith synapses while having no effect on the overall integrity of LDNat10(cid:1)Mhadsignificantlydecreasedmonoubiquitinlev- dendrites.Wealsoexaminedwhethertherewasaconcomitant els (Fig. 2E). On average, we observed a 40% reduction in alterationinthedensityofsynapticproteinpuncta.Wefound 7862•J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868 Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 that the density of PSD-95 puncta was decreased by 30% (Fig. 3E) (control, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.04; LDN-treated, 0.8 (cid:8) 0.3). However, we did not observe any changesinthenumberofShank,surface GluR1, Synapsin I, and Bassoon puncta (Fig.3E).Todemonstratethespecificity ofourUCH-L1inhibitor,neuronswere treatedwithaUCH-L3inhibitor(LDN- L3). UCH-L3 is a closely related DUB andhasalsobeenshowntobeinvolved ingeneratingfreemonomericubiquitin. However,wedidnotfindanyalterations in synaptic structures in LDN-L3- treated neurons (supplemental Fig. S3A–C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Together, thesedatashowthatUCH-L1activityis specifically involved in maintenance of synapsestructure. UCH-L1regulatesspinemorphology anddensity Abundant evidence demonstrates that spines undergo activity-dependent changesinshapeandnumber,andthere- fore, spines could serve as a cellular sub- strateforchemicalandstructuralsynaptic plasticity (Segal, 2002, 2005). Therefore, weaskedwhethertheobservedalterations inthesynapticproteinclusterscouldpos- sibly be accompanied by any changes in spine size and density. To detect alter- ations in spine morphology, we analyzed spines from GFP-expressing neurons treated with vehicle or LDN. We found Figure3. InhibitionofUCH-L1activityalterssynapticstructure.A–C,CulturedneuronsweretreatedwithLDNfor24h.Atthe strikingalterationsinthesizeofspinesin endofLDNtreatments,neuronswerefixed,permeabilized,andimmunolabeledwithanti-PSD-95andanti-SynapsinI(A), LDN-treatedneurons.Spinesexhibitedan anti-Shankandanti-Bassoon(B),orlive-labeledwithanti-GluR1forsurfaceGluR1staining,andthenfixedandstainedwith enlargementof(cid:2)80%inspineheadwidth anti-PSD-95andanti-MAP2antibodies(C).Representativemaximumz-projectedconfocalimagesandstraighteneddendrites and 37% increase in spine length (Fig. fromcontrolandLDN-treatedneuronsaredepicted.Scalebar,5(cid:1)m.D,E,Presynapticandpostsynapticproteinpunctasizeand 4C,F) (spine head width, control, 1.0 (cid:8) numberwereanalyzedincontrolandLDN-treatedneurons.ThemeanpunctasizeandnumberinLDN-treatedneuronswere 0.09; LDN-treated, 1.8 (cid:8) 0.22) (Fig. normalizedtothoseofcontrolneuronsfromthreetofourindependentexperiments.Thenumberofpunctawascalculatedper10 4D,G)(spinelength,control,1.0(cid:8)0.03; (cid:1)mdendritelength.Measurementsforindividualstainingsweremadeonthefollowingnumberofdendritescorrespondingto LDN-treated, 1.37 (cid:8) 0.08). We also ob- controlandLDN-treatedneurons,respectively:PSD-95,84and99;Shank,70and102;SynapsinI,46and55;Bassoon,66and93; servedthatblockingUCH-L1activitydra- andGluR1,51and56.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMareshown.Forstatisticalanalysis,unpairedStudent’sttestwasperformedbetween anytwoconditions.*p(cid:9)0.001. matically reduced the number of spines (Fig. 4E). LDN-treated neurons had a (cid:2)50% reduction in the number of spines compared with the changes observed in spines were accompanied by alterations controluntreatedneurons(spines/micrometer:control,0.72(cid:8) intheactincytoskeleton.Tovisualizeactin-filledspines,neu- 0.05; LDN-treated, 0.35 (cid:8) 0.05). These data demonstrate that ronswereinfectedwithYFP-actinSindbisvirus(supplemen- alterations in synaptic structure induced by inhibition of tal Fig. S4, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental UCH-L1activityarealsoaccompaniedbychangesinspinemor- material).Inlinewithourpreviousobservation,wefoundthat phology.Indeed,weobserveda30%decreaseinthedensityof YFP-actin-filled spines were enlarged in neurons that were PSD-95 puncta in LDN-treated neurons. This potentially indi- treated with LDN. In addition, neurons were stained with catesthatspinelossprecedesthedisassemblyofthepostsynaptic phalloidin to label F-actin in dendritic spines (supplemental densityinUCH-L1-inhibitedneurons. Fig. S4B,C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental Filamentous actin (F-actin) accumulates at high concen- material).WefoundthatF-actinpunctatoalsobeenlargedin tration in dendritic spines, and actin filaments provide the LDN-treatedneuronsandthattheycolocalizedwithsynaptic structuralbasisforcytoskeletalorganizationinspines.Actin- markers PSD-95 (supplemental Fig. S4B, available at www. based changes in the morphology of spines are regulated by jneurosci.org as supplemental material) or Shank (supple- synaptictransmissionandareknowntocontributetosynaptic mental Fig. S4C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supple- plasticity (Fischer et al., 1998, 2000; Fukazawa et al., 2003; mentalmaterial).Together,ourdataindicatethatalterations Okamoto et al., 2004). We examined whether structural to the actin cytoskeleton occur concomitantly with altered Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868•7863 sitieswithanaveragelengthof0.64(cid:8)0.04 (cid:1)m (Fig. 5I–K). The synaptic terminals were irregular and contained abundant clearsynapticvesiclesandcoatedpits(Fig. 5F).Thedendriteswerealsoirregularand displayedenlargedmitochondria,andfo- cal vacuolization (Fig. 5G,H). Together, ourEMstudiescorroborateourimmuno- fluorescencestudiesandfurthersubstanti- atearoleforUCH-L1functioninmain- tainingnormalsynapticstructure. AlteredUCH-L1activityaffectssynaptic proteincomposition Since inhibition of UCH-L1 activity re- sulted in a reduction in the levels of free monomericubiquitinandstructuralalter- ationsatsynapses,weaskedwhetherthese changeswereaccompaniedbyalterations inthestabilityofsynapticproteins(Fig.6). Oftheproteinsexamined,weonlyfound alteredPSD-95expressionlevelsinLDN- treated neurons. We observed a 60% in- creaseinthelevelsofPSD-95inneurons treated with LDN (Fig. 6A,C) (control, 1.0(cid:8)0.12;LDN-treated,1.6(cid:8)0.16).We alsoexaminedproteinexpressionlevelsin brain homogenates obtained from wild- type and UCH-L1-deficient mice (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, we found that protein expression levels of PSD-95 and Shank were increased by 70 and 47% in mouse brain homogenates deficient in UCH-L1 activity (Fig. 6D) (PSD-95, wild type, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.15; UCH-L1 null, 1.7 (cid:8) 0.19; Shank,wildtype,1.0(cid:8)0.09;UCH-L1null, 1.47(cid:8)0.10).Thesedatashowthatlossof Figure4. InhibitionofUCH-L1activityaltersspinesizeanddensity.A,B,CulturedneuronsweretreatedwithLDNfor24h. UCH-L1activityaffectsthestabilityofcer- EGFPSindbisvirionswereaddeddirectlytoculturemediaafter10–12hofLDNtreatment,andproteinexpressionwasallowedto continuefor12–14h.AttheendofLDNtreatments,neuronswerefixed,permeabilized,andimmunolabeledwithanti-PSD-95 tainscaffoldproteinsbutnotallsynaptic andanti-SynapsinIantibodies.ThestraighteneddendritesinBcorrespondtotheregionsindicatedbyarrowsinthewhole-cell proteins. imagesinA.C–G,Quantificationofthenumber,widths,andlengthsofGFP-filledspinesincontrolandLDN-treatedneuronsis shown.C,D,Measurementsforspineheadwidthsandspinelengthswerenormalizedtothoseofcontrolvalues.F,G,Cumulative EffectsofUCH-L1inhibitiononglobal frequencyplotsshowingdistributionofspineheadwidth(inmicrometers)andspinelength(inmicrometers)incontroland UPSactivity LDN-treatedneuronsareshown.E,Quantificationofspinedensityisrepresentedasthenumberofspinesper1(cid:1)mdendrite Since our data clearly demonstrate that length.Thequantifieddatawereobtainedfromthreeindependentexperiments,inwhich(cid:5)20dendritesand(cid:5)900spineswere blockingUCH-L1activityreducesthelev- analyzedpercondition.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMareshown.*p(cid:9)0.05,**p(cid:9)0.01,unpairedStudent’sttest. elsoffreemonomericubiquitin,wesetout todeterminewhetherinhibitingUCH-L1 presynapticandpostsynapticproteinpunctaandspinesizein activityplaysaroleinmodulatingglobalUPSfunction.Weas- UCH-L1-inhibitedneurons. sessedproteasomeactivityinvitrobymonitoringthecleavageof TofurtheranalyzetheeffectsofUCH-L1inhibitiononsyn- a synthetic fluorogenic substrate (Suc-LLVY-AMC) in total ly- aptic structure, we performed electron microscopy on LDN- sates from control and LDN-treated neurons and detected no treatedneurons(Fig.5).Inuntreatedhippocampalcultures,as differencesbetweenconditions(Fig.7A).Sinceoneofthemajor expected,abundantandwellorganizedneuriticprocesseswere functions of UCH-L1 is generating free ubiquitin, we assessed identified (Fig. 5A–D). Most synaptic contacts were synapto- whetheralteringubiquitinlevelsbyoverexpressingUCH-L1has dendritricratherthanaxo-somatic.Onaverage,presynapticter- anyeffectonUPSactivity.Wegeneratedwild-typeandmutant minalscontained81.4(cid:8)6.2vesiclespersynapseandmeasured GFP-taggedUCH-L1mammalianexpressionconstructs.Allof 0.89(cid:8)0.07(cid:1)mindiameter,displayingsymmetricalpostsynaptic ourconstructswereequallyexpressedinHEK293Tcells(Fig.7B, densitiesof(cid:2)0.59(cid:8)0.06(cid:1)minlength(Fig.5I–K).Incontrast, top panel). Furthermore, HAUb-VME labeling assay on these hippocampalculturestreatedwithLDNdisplayedabnormalpre- lysatesshowedwild-typeUCH-L1-GFPtobeactive,whereasno synapticandpostsynapticterminals(Fig.5E–H).Thepresynap- activitywasdetectedforeitherthecatalyticallyinactiveC90Sor ticterminalscontainedonaverage107.2(cid:8)6.2vesiclespersyn- ubiquitin binding-deficient D30A mutants (Fig. 7B, bottom apseandwereenlarged,averagingindiameterfrom1.64(cid:8)0.14 panel).Ourdataareconsistentwithpreviousreportsdescribing (cid:1)mindiameter,anddisplayedthickenlargedpostsynapticden- theseUCH-L1mutants(Sakuraietal.,2006).Wenextexamined 7864•J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868 Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 Figure5. UltrastructuralsynapticalterationsinprimaryneuronstreatedwithLDN.A–H,Representativeelectronmicrographsofculturedneuronstreatedwithvehicleor10(cid:1)MLDNfor24h. A–D,Control,untreatedneuronsexhibitnormalcharacteristicsforpresynapticterminals(pst),postsynapticdensities(psd),mitochondria(m),anddendriticprocesses(dp).E–H,LDN-treated neuronsdisplayabnormalsynapticstructuresdemonstratedbyenlargedpresynapticterminals,irregularpostsynapticdensities,abundantcoatedpits(cp)andclearsynapticvesicles(sv),and vacuolizationofdendrites.Magnification,30,000(cid:6).QuantificationsofPSDdiameter(I),numberofvesicles(J),andsynapticzonecontact(K)incontrolandLDN-treatedneuronsareshown. Averagedresultsfromatotalof10micrographsforeachgrid(9gridspercondition)wereusedfordataanalysis.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMareshown.*p(cid:9)0.01,unpairedStudent’sttest. thelevelsofpolyubiquitinconjugatesbyWesternblotanalysisas UCH-L1(supplementalFig.S5A,B,availableatwww.jneurosci. itisknownthatinhibitionoftheproteasomeactivitycandirectly org as supplemental material). Together, these experiments affectthelevelsofubiquitin-conjugatedproteins.Interestingly, suggest that altered UCH-L1 activity does not directly affect althoughwefoundthatoverexpressionofwild-typeormutant proteasomefunction.Furthermore,anincreasedmonomeric UCH-L1-GFP had no effect on the levels of polyubiquitinated ubiquitinlevelsgeneratedbyoverexpressionofUCH-L1does proteins(Fig.7C,toppanel),therewasanapproximatelyfour- nothaveaneffectonthelevelofpolyubiquitinconjugatesand foldtofivefoldincreaseinthelevelsoffreemonomericubiquitin proteasomefunction. in cells overexpressing wild-type and the C90S mutant of However,tobetterdeterminewhetherglobalUPSfunctionis UCH-L1 (Fig. 7C, middle panel; D) (GFP, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.16; wild- affected,wemonitoredthedegradationofGFPuinhippocampal typeUCH-L1,4.3(cid:8)0.23;C90S-UCH-L1,4.7(cid:8)0.67;D30A- neuronsusingtime-lapseconfocalmicroscopy.Weusedapho- UCH-L1, 0.97 (cid:8) 0.07). These data are quite interesting be- toactivatablevariantofGFPu(paGFPu),whichisaUPS-specific cause although both the C90S and D30A mutants lack reporter protein substrate and requires polyubiquitination for hydrolytic activity, the C90S mutant still maintains its ubiq- degradationbytheproteasome(Benceetal.,2005).Weobserved uitin binding ability, which is thought to be important for a 50% decrease in the degradation rate of paGFPu in LDN- stabilizing ubiquitin levels (Osaka et al., 2003; Sakurai et al., treatedneurons(Fig.7E,F).Together,thissuggeststhatthecata- 2006).Wealsomeasuredproteasomeactivityinvitroinlysates lytic activity of the proteasome is not affected by decreased from wild-type and mutant UCH-L1 overexpressing HEK UCH-L1activity.However,UCH-L1inhibitioncanaffectglobal 293Tcells.Wedidnotdetectanychangesinproteasomeac- ubiquitin-dependent UPS function, most likely because of de- tivitylevelsbetweenwild-typeandC90SorD30Amutantsof creasedmonomericubiquitinlevels. Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868•7865 there was no significant difference in the density of PSD-95 punctabetweencontrol(GFPandDMSO-treatedneurons)and myc-ubiquitin-expressingneurons(Fig.8A–D,F)(GFP-DMSO, 1.0(cid:8)0.04;ubiquitin-DMSO,0.97(cid:8)0.05;GFPplusLDN,0.89(cid:8) 0.03;ubiquitinplusLDN,1.1(cid:8)0.03).Moreover,expressionof ubiquitinitselfhadnoeffectonsynapticstructure.Together,our datademonstratethatreductionsinthelevelsoffreemonomeric ubiquitinbecauseofthelackofUCH-L1activityleadtomajor structuralsynapticalterationsinhippocampalneurons. Discussion Activity-dependent remodeling of synaptic connections in the brain is thought to be crucial for modulations in synaptic strength.Recently,theUPShasbeenshowntobeanimportant factor for this remodeling and for synaptic plasticity. Interest- ingly, very little is understood about the UPS components in- volvedandtheirregulationatsynapses.Inthepresentstudy,we setouttounderstandthefunctionofUCH-L1,thehighestex- pressed DUB in the brain, at synapses to uncover regulatory mechanismswhichexistinneuronstocontrolitsfunction.Our data demonstrate that UCH-L1 is distributed throughout so- maticanddendriticcompartmentsofhippocampalneurons.Us- ing a specific substrate that can monitor UCH-L1 activity, we showthatUCH-L1ispartiallyactiveintotallysatesfromcultured neuronsandinthepostsynapticdensityfractionspreparedfrom rat brain. Strikingly, however, we found that NMDA receptor activationrapidlyincreasesUCH-L1activityandconcomitantly increasesfreemonomericubiquitinlevels.Furthermore,block- ingUCH-L1activitybyLDNsignificantlyreducedthelevelsof monomeric ubiquitin. Together, these findings suggest that UCH-L1 may be responsible for modulating the levels of free monomeric ubiquitin pools available for various cellular pro- cesses. Furthermore, NMDA receptor-dependent activation of UCH-L1 may potentially have a significant effect on synaptic transmission by controlling ubiquitin levels in neurons. This novelfindingisthefirstreportdemonstratingthatthefunctionof UCH-L1ismodulatedbyneuronalactivity. ManytargetsoftheUPSexistatsynapsesincludingscaffold Figure6. ComparisonofsynapticproteinexpressionlevelsincontrolandLDN-treatedneu- and structural proteins whose function is critical for several ronsandinwild-typeandUCH-L1-deficientmousebrains.A,B,LysatesfromcontrolandLDN- forms of plasticity (Patrick, 2006; Yi and Ehlers, 2007). Since treatedculturedneurons(A)orhomogenatesfromwild-typeandUCH-L1-deficientmouse decreased UCH-L1 activity is associated with several neurode- brains(B)weresubjectedtoWesternblotanalysis.C,D,Relativebandintensitieswerequan- generativedisorders,andpharmacologicalinhibitionofUCH-L1 tifiedandnormalizedtothoseofcontrolneuronsorwild-typemousebrains.Thequantified datawereobtainedfromtwoandfourindependentexperimentsforbrainhomogenatesand activitysubstantiallyreducesLTP,weassessedanystructuralal- LDN-treatedneurons,respectively.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMareshown.*p(cid:9)0.01,unpairedStu- terationstosynapsesinUCH-L1-inhibitedneurons.Wefound dent’sttest. that spines became greatly enlarged in LDN-treated neurons whiletheirdensitysignificantlydecreased.Theseenlargedspines were associated with presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins, in Ectopicexpressionofubiquitinrestoressynapticstructurein particular, important scaffold proteins such as PSD-95 and LDN-treatedneurons Shank.Wefoundapositivecorrelationbetweenthesizeofspines ThemajorfunctionofUCH-L1isthoughttomaintainthelevels and the size of synaptic protein clusters associated with those offreemonomericubiquitinusedforvariouscellularprocesses. spines. Furthermore, we observed alterations to the actin cy- Todeterminewhetheralterationinsynapticstructureinducedby toskeletonastherewasasignificantaccumulationofF-actinin inhibitionofUCH-L1weremainlyattributabletoareductionin spines. The increased spine size together with the striking de- thelevelsoffreemonomericubiquitin,weperformedubiquitin crease in spine number potentially reveals heterogeneity in the rescueexperimentsinLDN-treatedneurons(Fig.8).Wefound sensitivitytoalteredmonomericubiquitinlevelsbetweenspines. thattheexpressionofubiquitinfor12hcompletelyrescuedthe ThesealterationsinsynapticstructuremaycontributetotheLTP effects of UCH-L1 inhibition on PSD-95 size and distribution. defects observed in UCH-L1-inhibited neurons (Gong et al., AlthoughPSD-95punctawasincreasedinLDN-treatedneurons, 2006).Wealsoanalyzedthedensityofsynapticproteinpuncta theexpressionofmyc-ubiquitincompletelyblockedtheeffectof andfoundadecreaseonlyinPSD-95.Thiscouldreflectchanges LDN (Fig. 8A–E) (GFP-DMSO, 1.0 (cid:8) 0.05; ubiquitin-DMSO, inthestabilityortraffickingofPSD-95.Indeed,theretentionof 0.93 (cid:8) 0.04; GFP plus LDN, 1.6 (cid:8) 0.04; ubiquitin plus LDN, PSD-95inindividualspineshasbeenshowntobehighlydynamic 1.0(cid:8)0.03).Aspreviouslyobserved,therewasaslightdecreasein (Grayetal.,2006).Wealsoanalyzedproteinexpressionlevelsfor thedensityofPSD-95punctainLDN-treatedneurons;however, severalsynapticproteinstodeterminewhethertheobservedal- 7866•J.Neurosci.,June17,2009•29(24):7857–7868 Cartieretal.•RegulationofSynapticStructurebyUCH-L1 terationsinthesizeordensityofsynaptic punctacorrelatedwiththeirstability.We only detected changes in the protein ex- pressionlevelsofPSD-95andShank.Al- though the levels of PSD-95 increased in both LDN-treated neurons and brain ly- sates from UCH-L1-deficient mice, the levels of Shank protein expression were only elevated in the brains of UCH-L1- deficientmice.However,itisquiteplausi- blethatthestabilityofsynapticproteinsis not equally sensitive to altered UCH-L1 activityand/orlevelsofmonomericubiq- uitin. Alternatively, UCH-L1 may have specifictargetsinneuronsasotherinter- actingpartnersforUCH-L1havebeenre- ported (Caballero et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002;Kabutaetal.,2008).However,itis alsofeasibletohypothesizethatdecreased UCH-L1activityresultsindecreasedmo- nomeric ubiquitin levels, which elicits a pathogenicprogramthatinitiateswiththe lossofunstablespineswithaconcomitant redistributionandaccumulationofsynap- ticproteinssuchasPSD-95andShankinto more stable spines. Strikingly, we found that overexpression of ubiquitin restored normalsynapticstructureinLDN-treated neurons.Thisindicatesmonomericubiq- uitin levels to be regulatory for normal synaptic structure. Together, these find- ingspointtoasignificantroleofUCH-L1 insynapticremodelingbymodulatingfree Figure7. EffectsofalteredUCH-L1activityonUPSfunction.A,CulturedneuronsweretreatedwithvehicleorLDNfor24h. ubiquitinlevelsmostlikelyinanactivity- ProteasomeactivitywasmeasuredintotalcelllysatesfromcontrolandLDN-treatedneuronsinvitrobyfluorimetricassayusinga dependentmanner. Suc-LLVY-AMCfluorogenicsubstrate.RelativefluorescenceunitsovertimeincontrolandLDN-treatedneuronsareshowninaline Does altered UCH-L1 activity affect graph.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMoffiveindependentexperimentsareshown.B–D,HEK293Tcellsweretransfectedwithwild-type, UPS function? To address this question, C90SandD30AUCH-L1-GFPconstructsfor48h.B,ExpressionlevelsofGFP,wild-type,andmutantUCH-L1-GFPwereassessedby weexaminedproteasomeactivitylevelsin Westernblotanalysis.Immunoblotswereprobedwithanti-GFPantibody(toppanel).Activitylevelsofwild-typeandmutant vitroincontrolandLDN-treatedneurons. UCH-L1-GFPwereassessedbyDUBlabelingassay(HAUb-VME)oflysatesfromHEK293T-transfectedcells.Arepresentative Westernblotoflabeledlysatesisdemonstrated(bottompanel).C,Expressionlevelsoffreemonomericubiquitinandpolyubiq- Wedidnotdetectanychangesinprotea- uitinconjugatesintransfectedHEK293Tcellsareshown.Westernblotprobedwithanti-UCH-L1andanti-CDK5(loadingcontrol) someactivitylevelsmeasuredintotalcell antibodiesdemonstratingequalexpressionlevelsofwild-typeandmutantUCH-L1-GFPandequalproteinloading,respectively. lysates from control and UCH-L1- D,RelativeintensitiesoffreemonomericubiquitinlevelsinGFP,wild-type,andmutantUCH-L1-GFPtransfectedcellsobtainedby inhibitedneurons.Kyratzietal.(2008)re- densitometryanalysisofubiquitinblotsfromthreeindependentexperiments.Meanvalues(cid:8)SEMareshown.*p(cid:9)0.01, ported similar findings. They found that unpairedStudent’sttestbetweencontrol(GFP)andanytestgroup.E–G,CulturedneuronsweretreatedwithLDNfor24h.paGFPuvirions the loss of UCH-L1 in neurons derived wereaddeddirectlytoculturemediaafter10–12hofLDNtreatment,andproteinexpressionwasallowedtocontinuefor12–14h.E, fromgadmicedidnotaffectproteasome Representativestraighteneddendritesoftime-lapseexperimentsfromcontrolorLDN-treatedculturedneuronsexpressingpaGFPuare activity when assayed in vitro. Further- shown.Scalebar,10(cid:1)m.F,Groupedanalysis(plottedaslinegraphs;mean(cid:8)SEM)ofdendriticpaGFPufluorescenceintensitynormalized more,theyalsofoundthatoverexpression totime0forcontrol(paGFPualone)orLDN-treatedneurons.LiveimagingofpaGFPudegradationwasmadeon6and11cells,two ofwild-typeUCH-L1,whichsignificantly dendritespercell,fromcontrolandLDN-treatedneurons,respectively.RFU,Relativefluorescenceunit.Thecolorlook-upscaleforpaGFPu degradationisblack(lowest)towhite(highest).*p(cid:9)0.01,unpairedStudent’sttest. upregulated free monomeric ubiquitin levels,didnotalterproteasomeactivityin vitro (Kyratzi et al., 2008). This is consistent with our findings uitination(Benceetal.,2005).Indeed,thestabilityofPSD-95 (supplemental Fig. 5A,B, available at www.jneurosci.org as and Shank, two PSD scaffolds shown to be regulated by supplemental material). This would suggest that the excess ubiquitin-mediatedproteasomaldegradation,issignificantly availabilityofmonomericubiquitindoesnotincreasethepro- increasedinUCH-L1-deficientmice. teolytic activity of the proteasome. Interestingly, however, a Together,ourfindingshaveuncoveredanovellinkbetween significant decrease in the degradation rate of the paGFPu neuronal activity, UCH-L1 function, the maintenance of free reporter was found in neurons that were treated with LDN. monomericubiquitinlevels,andtheregulationofsynapticstruc- This could potentially reflect the sensitivity of our live- ture.Importantly,thisstudysuggeststhatalteredsynapsestruc- imagingreporterassaystoalteredubiquitinlevelsinUCH-L1- turecausedbythemisregulationofUCH-L1activityandmono- inhibitedneurons.Althoughourinvitromeasurementofpro- meric ubiquitin homeostasis may serve as an underlying teasome activity is independent of substrate ubiquitination, mechanismfordefectsinsynapticplasticityseeninneurodegen- paGFPudegradationbytheproteasomeisdependentonubiq- erativedisease.

Description: