Table Of ContentCartoon by Sydney Harris, Physics Today, February 1988. Courtesy of Sidney

Harris and ScienceCartoonsPlus.com.

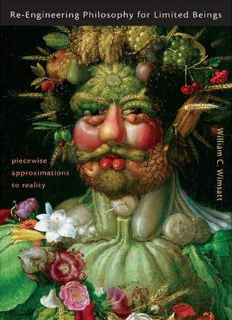

Re-Engineering Philosophy

for Limited Beings

W

PIECEWISE APPROXIMATIONS TO REALITY

WILLIAM C. WIMSATT

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 2007

Copyright Cl 2007 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wimsatt, William C.

Re-engineering philosophy for limited beings : piecewise approximations

to reality f William C. Wimsatt.

p. em.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-674-01545-6 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-674-01545-2 (alk. paper)

1. Philosophy. I. Title.

B29.W498 2007

191--dc22 2006052988

To my generators and support-

past: my parents, Ruth and Bill Wimsatt

present: my partner in life, Barbara Horberg Wimsatt

future: our son, William Samuel Abell ("Upski") Wimsatt

Preface

In the early 1990s, when I finally decided it was time to put together the

papers that would become this volume, the tides of rationalism were

near their high-water mark. Game theory increasingly dominated eco

nomics and political science, and optimizers in economics were talking

to those in biology. Rationalism had been strong in philosophy for my

entire professional generation, beginning in the mid-1960s. Natu

ralism's hold seemed less certain. Realism seemed on the retreat, not

only within philosophy but also with the rise of science studies.

Now we see a growing and refreshing empiricism about many things

"philosophical," even rationality itself. Traditional idealizations seem

less satisfactory on all sides. New disciplines have emerged, intersecting

many of our knottiest problems of the biological and human sciences

those problems often called methodological or conceptual or philosoph

ical, and increasingly described as complex, in the senses of chapters 8,

9, and 10 of this volume. Behavioral decision theory has begun to have

its day. Gigerenzer, Hutchins, and others project a more heuristic, col

lective, and contextually imbedded image of our intellectual powers. An

explosion in the past decade of works on human biological, cognitive,

social, cultural, and above all collective evolution have made it only

natural to look for our human natures through a historically and so

cially informed multidisciplinary scientific perspective. The human sci

ences and the Darwinian sciences, cluster terms emerging in the past

decade, are both appropriately named and increasingly interpene

trating. Perhaps Herbert Simon and Donald Campbell's different but

viii · Preface

consilient evolutionary visions of our kind will come to pass {see more

on this below).

But there is also a lively antiscientism abroad opposing this-perhaps

largely in response to the excessive reductionism of the past generation.

Philosophers like John MacDowell see scientific perspectives on human

nature as too coarse, rigid, and insensitive to capture our intentional

worlds of mind and culture. Past materialisms have regularly promised

urban renewal of these neighborhoods to make room for the latest

seemingly spare materialism, bringing a bulldozer when a cultural li

aison mission was called for. This is not the form of integrative materi

alism now emerging. Scientific-cultural liaisons now blossom, and new

progress in all of the human and Darwinian sciences could result from

richer and more appreciative interdisciplinary interactions. Hopefully,

enough practitioners of traditional disciplines will recognize that it is

again time for new infusions for the health of all and will resist the

temptation to erect defensive conceptual trade barriers. The ironies of

the frontispiece simultaneously document the hubris of a too-simple

physics-inspired reductionism, and my commitment to "everything in

between." It is thus a singularly suitable way to begin this book. I thank

Sidney Harris for permission to use his inspired wry insights on the

human scientific condition.

The oldest of these chapters goes back more than 30 years; the

youngest, only a few months. It has been about 25 years since Lindsay

Waters suggested that I put a book of them together, and I'm happy

now to surrender my seniority as his longest-standing project though it

has evolved from a collection of papers to a more systematic work. He

has maintained an ongoing conversation and stream of suggestions

(readings as well as modulations) all along. For years I didn't have the

right mix, and others developed alongside. These are, I hope, the first of

more "right mixes" to come. This collection combines older papers,

newer ones (several never before published and written especially for

this volume), and substantial new introductory essays.

With the older papers (chapters 4-6 and 8-11) I have made only

minor stylistic revisions, removed old misprints, and occasionally

added new bibliographical references. ChapterS's section on group se

lection was reorganized to eliminate redundancies with Chapter 4.

These papers have aged well-often anticipating newer directions and

still relevant as they stand, though references and descriptions of other

positions are occasionally dated. When not central to the argument, I

have left them unchanged. I apply a naturalistically conceived ration-

Preface · ix

ality to the analysis of the complex world we live in, and to what kinds

of beings we are that we do so. I hope the collection has the right hooks

and balance to interest scientists and philosophers alike. It is a natura

listic and realist philosophy of science for limited beings studying a

much less limited world. It mines science for philosophical lessons more

commonly than the reverse. The key concepts here (robustness,

heuristic strategies, near-decomposability, levels of organization, mech

anistic explanation, and generative entrenchment) are applied to ex

plore the cognitive tools with which we approach the world and our

parts in it. Reductionism-the source of past and continuing threats of

assault from below on the human sciences and humanities-is both

target and resource, as much for its methodology as for its results. The

result is a softer, richer vision of our world and our place in it than

promised by both sides in the history of the warfare between men

talisms and materialisms. It is a more appropriate philosophy of sci

ence, I argue, than we have been given so far.

Acknowledgments are spread through the chapter endnotes. The new ma

terials (chapters 1-3, 7, most of 12, and 13; the part introductions; and

the appendixes) emerged during and between several "writing retreats." I

thank the staff of Villa Serbelloni, the Rockefeller Foundation Center at

Bellagio (in a warm, dry, beautiful, and amicable March 1997), the

Franke Humanities Center at Chicago (for another part of that year, and

of 2004-2005), and finally the staff and fellows of the National Humani

ties Center in Research Triangle Park of Raleigh-Durham, North Car

olina, for a glorious year in 2000-2001. Their catalyses were real, though

nominally directed toward other projects, now further along and better

than they would have been without their help. Some chapters benefited

from the support of the National Science Foundation and the System De

velopment Foundation, and my students, undergraduate and graduate,

played a continuing role as midwives and sounding boards, many even as

they developed their own careers. Particularly among these (in temporal

order) have been Bob Richardson, Bill Bechtel, Bob McCauley, Jim

Griesemer, Sahotra Sarkar, Jeffrey Schank, and Stuart Glennan. Schank

and Griesemer coauthored multiple papers (and Schank, software) with

me in the process, and were particularly productive for my own thought.

Deeply formative influences of Herbert Simon, Donald Campbell,

Richard Lewontin, Richard Levins, and Frank Rosenblatt all began for

me in the mid-1960s, and have endured. Michael Wade's example and re-

Description:Analytic philosophers once pantomimed physics: they tried to understand the world by breaking it down into the smallest possible bits. Thinkers from the Darwinian sciences now pose alternatives to this simplistic reductionism. In this intellectual tour--essays spanning thirty years--William Wimsatt