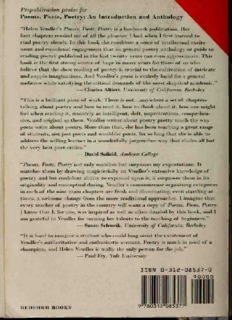

Poems, Poets, Poetry: An Introduction and Anthology PDF

Preview Poems, Poets, Poetry: An Introduction and Anthology

POEMS, POETS, POETRY An Introduction and Anthology Helen Vendler HARVARD UNIVERSITY & Bedford Books ofSr. Martin's Press Boston FOR BEDFORD HOOKS PRESIDENT AND PUBLISHER Charles H. Ghtisterueri GEKEFLAL MANAGER. AND ASSOCIAIE PUBLISHER;Joau B Fcinberg MANAGING EDITOR: Elizabeth M. Sehaaf DEVELOPMENTAL EDLTOR: Stephen A. Seipione EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS: Laura Arcan. Mart Retinoid Sweeny PRODUCTION EDITOR: Aim PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS: lit]]McKenna,Stasia Zaoijtgwikj, F.3!cn Thibault CopVEEtJTOR Maria Ascher TEXT DESIGN: Anna George COVER. DESIGN San Eiscntnan Library of Congress CatalogCard Number:95—80802 Copyright © 1997 by Bedford Books A Division of Sr. Martin's Press. Inc. All rights reserved. No parr of tlus book may be reproduced,stored m a retrieval system, or transmitted byany fom or by any means,electronic. mechanical, pho tocopying, recording, or otherwise. except as may be expressly permitted by the .ipplieablccopyrightstatutes or in writing by the lhtbLisher Manufactured in the United States of America. I 0 9 S 7 f e d c b a For.fafommion, Mite: Medford liooki, 75 Arlington Street. Boston. MA <>2116 (617 426-7440) ISI1V 0-312-085.17-0 Acknowledgments Sherman Ale.vie, "EvuLuticm1 and :LRjiservati-oti Love S6*ig" reprinted (font Tin ifFrintydniitltig©1992 byShertnati Alexte, by permission ol 1l.my- ingLoose Press "On dieAmtrait from Bostonto NewYork City" reprinted from Fir.9 Indian en rfn- Afiwrr © 1993 by Sherman Alexic, by permission oi Hanging Loose Press, Elizabeth Alexander, "Nineteen" and "Ode"from 77ie Venus Ht&tnirt, by Eliza herb Alexander, Used by permission of the University Pressof Vtrgiili.1 Paula Gunn Allen,"Zen Americana" reprinted from Coyotes Daylight Idp. Albu Ljuerique: I.a Confluent't.i Press, & 1978. Reprinted hy permission til die author. jichtUndfÿgnttHIS and Copyrights are conUrttied at flit hath ef flrr initdf.(m VOgtS 6dO 7 udncti AuJjfifltfi arr rxH’jUran if theCopyrightpo\te. It is ct violoticm eftIlf lawto irpppdrrcd' these sekttiotts l>y any IMCUFIU u-hotsotvtri without the written permission <f the copyright holdn Preface: About This Book This book offers ways to read and understand poems with the pleasure theydeserve. Its ninechaptersin PartI approachthepoemfrom various directions, in the conviction that any artwork invites consider¬ ation from different perspectives. Chapter 1,"The Poem as Life/' uses several short poems to show how a poetic utterance springs from a — life-moment sometimes a private one (falling in love), sometimes a public one (the decline of an aristocracy). Chapter 2, “The Poem as Arranged Life,"considers thesame poems that appearin Chapter 1, but this time treats them as arrangements, rather than as utterances; it asks why the poem takes the imaginativeshape itdoes, and how itselements havebeenordered. In Chapter3,"Poemsas Pleasure,"aspectsofpoetry' that give pleasure are mentioned and illustrated: formal aspects such as rhythm and rhyme, of course, but also construction and images; the¬ matic aspects such as poignancy and wisdom, too, but in addition to these an individual personal language proper to each poet. Chapter 4, "Describing Poems,” and Chapter 5, “The Play of Language," suggest — some useful ways of describing poems by the class of poems they belong to, by the little plots they act out through grammar and syntax, by the speech acts they engage in. by the agents they choose to do the work of the poem, and so on. Chapter ft, "Constructing a Self/’ moves on to the psychological world of the poem. Since each poem is a fictive speech by an imagined speaker, how does the author make that speaker convincing? How is a v vl PREFACE: ABOUT THIS lioot credible self constructed on the page? The more abstract lyric self of — Chapterft ungendered,oftiospecified age or race,of nodetermined — country ‘is contrasted, in Chapter 7, "Poetry and Social Identity,” with the lyric self which is socially marked, as we encounter a speaker making clear her sex, or his race, or his age, or her sexual orientation. Oursenseof the purposeand theaudienceofa poem depends to a great extent on howtheselfofthespeaker isdefined.Chapter fl,"Historyand — Regionally,11takes upthe topics oftimeandspace the twogreataxes — on which all literature turns as they applytolyric poetry. And finally, in Chapter 9, "Attitudes, V—alues,Judgments,” the largest questions we can put to a literary work questions about its attitudes, values, and — judgments are raised and discussed with respect to some crucial ex¬ amples, old and new. Each of these chapters takes up several poems by way of illustra¬ tion, and each isfollowed by a section called “Reading Other Poems" that introduces a small groupofpoems which can be usefullyread in the light of that chapter. These arc usuallyshort poems,and range from the canonical to the recent.The anthology of Part II that follows these nine — chapters is intended to provide a wide sampling -more than 250 po¬ — ems from the literature of lyric, including some poems longer and more complex than those cited in thechapters. Arranged alphabetically by author, theanthology includes poems bymore than a hundred poets, many of them represented in significant depth soas tosuggest the range ofan individual poet’s work. Finally, my appendices on prosody,gram¬ mar,speech-acts, rhetorical devices,and lyricsubgenreiexist to provide further illustration of points taken upsubstantively hut not exhaustively — in individual chapters. The—y can help consolidate and extend when assigned as home reading the demonstrations given in class, I have also prepared a brief instructor’s manual in which I discusssome of the issues ofteaching poetry and suggest exercises that have, over the years, helped mv students understand and appreciate poetry. The manual also comments on most of the poems in Part I that are not discussed in the text’s nine chapters. Acknowledgments I'd like to thank ail the reviewers who helped improve this book by theIT detailed and incisive Suggestions, among them Charies Allied, University of California, Uerkeley; Paul Fry, Yale University; Vincent U. Leitch, Purdue University;Jcrcdith Memn, Ohio State University; Robert Phillips, UniversityofHouston;David Softcld, AmherstCollege; PkthAct: Anour THIS BOOK vii Susan Schweik, University of California, Berkeley; and George Stadc, Columbia University. 1 am grateful to Charles Christensen, joan Fein- berg, and Stephen Scipione at liedford Honks for their interest in this project, for their intuition about the shape it might take, and for their alert editorial guidance. ]would alsolike tothank Elizabeth Schajf,Ann Sweeney, Laura Arcari, Mark Rcimold, Alanya Harter, Maria Ascher, Bill McKenna, and Stasia Zomkowski, I was assisted throughout by my graduate assistant, Nick Halpem, now of North Carolina State Univer¬ sity,and by myadministrativeassistant, Susan Welby. Finally, I want to express my warmest gratitude to Sylvan l!amet, who first suggested ) write such a book, who had faith in its completion, and who selflessly read, as a friend, every word. His detailed comments were invaluable; and his patient counsel, in the ups and downs of revision, wasappreci¬ ated more than he will ever know and more than I can ever say. r About Poets and Poetry Poetspossess two talents: one is imagination,theotherisa mastery oflanguage. Many people, writers and nonwriters alike, see the world imaginatively: to accompany such people toa party or an exhibition or a play is tosee the event more keenlyand more vividly than one might have done atone. The world takes on more color; things art seen from a newslant; events are freshly interpreted and highlighted: a vivacity of response issummoned up. With onesort ofimaginative person, every¬ thing is seen more darkly: theguestsat the party seem trivial,grotesque; the exhibition is tragic;the playis an emblem ofdespair. In thecompany of an imaginative person of a different son, we see the world, as the cliche ha? it, through rose-coloredglasses:people seem better, the world kinder, the cause for optimism stronger. In short, imaginative people have the gift of making otherssee the world as they see it- And as the poet Wallace Stevens put it, “Things seen are things asseen," While many imaginative peoplearecontent tolet theirsenseofthe world,conveyed through conversation, vanish astheyspeak, writersfeel compelled tosetdowntheirperceptionsin writing.Writersoftensee the imagination, as Stevenssaw it, asa “third planet."Just as a given scene bolts one way in sunlight, another way in moonlight, so it looks yet a third way in the light of the imagination. "There's a certain slant of light." says Emily Dickinson;"In this blue light, 1 can take you there," promiscsjone Graham in"SanScpolcrcr."That isthe implicitinvitation be ABOUT POETS AND POETKY offered by all'writers: (hat you willsec things in a new light, the light of their construction of the world, — We read imaginative works whether epic, fiction, drama, or — poetry in order togain a widersense ofthereal.Our hungertoknow the world, bom with us and eager in childhood, finds one of its chief satisfactions in learning about the responses of others. Of course we are pleased to learn that others share our views, but we are also keenly interested to find out that others see the real differently from ourselves. This is partly a matteroftemperament(say.mournful versus humorous), partly a matter of experience (male VCTSUS female, young versus old), partly an accidental matter of what happens in a writer’s historical epoch (war versus peace) Someformsofliterature (wecancall them thesocial genres), such as epic, ficti—on, and drama, make us look at the wide panurama of asocial group a nation,a village,a family.Though all of the social genres used tobe written in poetry (Milton.Chaucer, Shake¬ speare), nowadays the social world is usually observed through prose, We know one America through the eyes of Herman Melville, another through Edith Wharton, yet another through Ralph Ellison. Each of them induces us to live for a while in the light of a fresh imagining of the United States. And in addition to an imagi—native view of America, each of these writers has a mastery oflanguage Melville's encyclope¬ dic and torrential language of whaling, Wharton's fastidious language of social difference,and Ellison’sbroodingand intenseintellectual language of the "invisible man." Butbesidesthenarrativeanddramaticsocial genres,thereexiststhe large body of poetry we call lyric. Lyric is the genre of private life: it is what we sayto ourselveswhen weare alone. Thee may bean addressee m lyric (God, or a beloved), but the addressee is always absent. (The dramatic monologue, a form Browning made famous, has a silent ad¬ dressee on stage, but this is the exception to the rule of the absent addressee.) Ina way,imagination isatitsmostunfetteredinlyricbecause the writer need notgivea recognizable portraitofsociety,asthe novelist or dramatist must, Liecause the lyric represents a moment ofinner me—d¬ itation,—it is relatively short, and always exists in a particular place — "here” and a particular time "now.”It mayspeak about the there and then, but itspeaks about them from the hereand now. Itlets usinto the innermostchamberofanother person's mind,and makes us privy to what he or she would say in completesecrecy and safety, with none to overhear. The diary is the nearest proseequivalent to the lyric, but a diary is seen by a readerasthe wordsofanother person, whereasa lyncis meant to be spoken by its reader as if the reader were the one uttering the ABOUT I’OETS \HD POETRY si words. A lync poem is script for performance by its reader. It is, then, the most ultimateofgenres,constructinga rwinship between writerand reader. And it is the most universa! ofgenres, because it presumes that that reader resembles the writer enough to step into the writer’s shoes and speak the lines the writer has written as though they were the reader’s own: Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry ] could not travel both And he one traveler, long!stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the unde—rgrowth. ROBERT FROST, "Tht Road NotTliter11 To read these tines is to be transformed into the hesitating speaker. We do not listen to him; we become him, Sometimes, ofcourse, thespeaker is more narrowlyspecified, asa certain type ot person or even as an individual. Yet even when there is 3cleardisparity of personal character as when I, a twentieth-century white American woman,am reading Idake's lyricspoken bya little black boy in eighteenth century England — the lyne poet expects that t Will put myselfintothesubject-position of thelittle black boy, and make the boy's words my own. Though some theorists have suggested that wc “overhear” the speaker oflync (makinglyric intoa kind ofmono-drama of which we arc the audience), it is more often true that I do not, as a disinterested spectator, overhear the lyric speaker; rather, the words of die speaker become my own words. Thisimaginative transformation of selt is what is offered to ns by the lync. Because lyric is a short form (unlike the epic or The verse-tale), it must be more concise than narrative ordrama. Everyword has tocount. So does every gap. fit fact, lyric depends on gaps, and depends even more on the reader to fill in the gaps. It is suggestive rather than ex¬ haustive. As the poet W. B. Yeats said in a !925 letter, referring to (but perhapswith lus own writingot lyric in mind), “Tell a little A' Jit' is Hamlet; tell all & he is nothing. Nothing has life except the incomplete.11In thefollowingpages,suggestionsare madeon how togo about exploring a lyric, in order to fill in us gaps and make the most of itshints,so that the courseof its emotionscan beunderstood ill their full subtlety. Even thoughlyricsometimes makesgreaterdemandson usthan do the more explicit genres, a poem always (if it is successful) attracts us enough to make us willing to bear with it while wc try to understand it

Description: