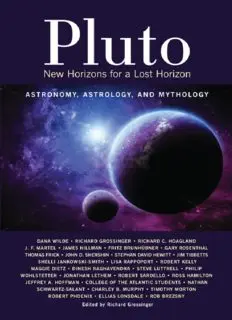

Pluto: New Horizons for a Lost Horizon: Astronomy, Astrology, and Mythology PDF

Preview Pluto: New Horizons for a Lost Horizon: Astronomy, Astrology, and Mythology

Copyright © 2015 by Richard Grossinger. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the written permission of the publisher. For information contact North Atlantic Books. Published by North Atlantic Books P.O. Box 12327 Berkeley, California 94712 Cover art by Aphelleon/Shutterstock.com Cover design by Susan Quasha “Hades” (pp. 27-32) from The Dream and the Underworld by James Hillman. Copyright © 1979 by James Hillman. Pluto: New Horizons for a Lost Horizon is sponsored and published by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences (dba North Atlantic Books), an educational nonprofit based in Berkeley, California, that collaborates with partners to develop cross-cultural perspectives, nurture holistic views of art, science, the humanities, and healing, and seed personal and global transformation by publishing work on the relationship of body, spirit, and nature. North Atlantic Books’ publications are available through most bookstores. For further information, visit our website at www.northatlanticbooks.com or call 800-733-3000. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pluto : New Horizons for a lost horizon : astronomy, astrology, mythology / edited by Richard Grossinger. pages cm Summary: “An anthology about Pluto, encompassing astronomy, mythology, psychology, and astrology with original essays and excerpts of classic required reading about our most famous dwarf planet”—Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58394-897-2 (pbk.)—ISBN 978-1-58394898-9 (ebk.) 1. Pluto (Dwarf planet) 2. Planets—Exploration. 3. New Horizons (Spacecraft) I. Grossinger, Richard, 1944– editor. QB701.P63 2014 523.49′22—dc23 2014039181 v3.1 Contents Cover Title Page Copyright INTRODUCTION Richard Grossinger 1 Pluto on the Borderlands Dana Wilde 2 Pluto and the Kuiper Belt Richard Grossinger 3 New Horizon … for a Lost Horizon Richard C. Hoagland 4 Pluto and the Death of God J. F. Martel 5 Hades James Hillman 6 Excerpts from Pluto Fritz Brunhübner 7 The Pluto/Persephone Myth: Evoking the Archetypes Gary Rosenthal 8 Old Horizons Thomas Frick 9 The Inquisition of Pluto: A Planetary Meta-Drama in One Act John D. Shershin 10 Pluto and the Restoration of Soul Stephan David Hewitt 11 Our Lady of Pluto, the Planet of Purification Jim Tibbetts 12 Love Song for Pluto Shelli Jankowski-Smith 13 I Feel Bad about Pluto Lisa Rappoport 14 Pluto Robert Kelly 15 Pluto Maggie Dietz 16 Falling in Love with a Plutonian Dinesh Raghavendra 17 Dostoevsky’s Pluto Steve Luttrell 18 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto Philip Wohlstetter 19 Plutonic Horizons, or My Sixty-Nine-Year Search for Planet X Philip Wohlstetter 20 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto Jonathan Lethem 21 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto Robert Sardello 22 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto Ross Hamilton 23 What the Probe Will Find, What I’d Like It to Find Jeffrey A. Hoffman 24 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto College of the Atlantic Students 25 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto Nathan Schwartz-Salant 26 The Ten Worlds of Pluto Charley B. Murphy 27 Ten Things I’d Like to Find on Pluto Timothy Morton 28 The End of the World Timothy Morton 29 My Father Pluto Robert Phoenix 30 Pluto is the Reason We Have a Chance Ellias Lonsdale 31 Pluto: Planet of Wealth Rob Brezsny ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS Introduction R G ICHARD ROSSINGER This anthology puts Pluto into scientific, cultural, and psychospiritual context in conjunction with NASA’s New Horizons mission, the centerpiece of which is the transit of an Earth-originating satellite with the dwarf planet and its moons on July 14–15, 2015. The dedicated capsule of instruments was launched atop an Atlas V rocket at 14:00 EST on January 19, 2006, from Pad 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Center in Florida after an eight-day delay, initially to allow last-minute testing of the rocket’s kerosene tank, then to avoid high winds and low cloud ceilings downrange. It is compelling to picture local weather on Earth affecting the delivery of a package at cloud-less, wind-less Pluto more than nine years later. A half hour after lift-off, the rocket’s Centaur second stage reignited the probe and sent it into a solar-escape speed and trajectory. New Horizons crashed lunar orbit in a mere nine hours and was out of the Moon’s gravitational field before midnight. As the scientific package zips 6,200 miles above a bleak Plutonian landscape—the Sun a bright star in perpetual night—Pluto becomes the last and farthest-flung member of the original nine-body Solar System to be imaged close-up through a transiting Homo-sapiens lens. But the book (or digital display) that you hold in your hand is not just a program guide for an engineering feat; it is the pursuit of a mytheme, an irreducible kernel with at least three manifestations: a god, an astrological organizing principle, and a planet. Pluto’s mythology, astronomy, astrology, science fiction, and politics form a series of semiotic networks that have to do less with imaging a far-off frigid rock and more with staring into a mirror of our own cosmology in crisis. Unmanned human assignation with a planet, though a mere mite floats above an orb hundreds of thousands of times its mass and size, is never innocent and without metaphysical consequences. Hours after Voyager’s close encounter with Uranus’s moon Miranda (January 28, 1986), the space shuttle Challenger exploded, driving NASA temporarily out of the heavens. Likewise when NASA put Galileo, a plutonium-238- driven satellite, on a 108,000-miles-per-hour suicidal plunge into Jupiter’s atmosphere (September 21, 2003), the collision sent a black nuclear cloud hurtling down through the planet’s cloud layers and changed everything about astrological Jupiter on Earth. Borderline planet, gadfly, and changeling object, Pluto is Earth’s Planet X, a vortex of seeds from beyond space and time, a quixotic 1930s dark body bundling inconclusive physical and paraphysical equations, a mischievous intruder in the zodiac who redefines every chart by the fact that his passage along its threshold evokes the imperceptible shock wave of the system itself. Pluto also crosses the destiny of the human enterprise at the moment that its own crisis transits with Pluto—a synchronicity inside the zodiac, which is Synchronicity Central anyway. Why that played out in interbellum 1930 with precisely that elusive trans-Neptunian pellet, and again at hailing distance in 2015, is a cosmic mudra of an unknown sphinx. But NASA could no more not go after this meme in its last gasp at completing a solar circuit than it could avoid putting a man on the Moon or send robots scuttling across equally inscrutable Martian deserts in their time. While perhaps little more than an escaped moon or common plutino exoterically, esoterically Pluto is an alchemical vas hermeticum, a vessel that, without revealing its nature, translates everything that comes into contact with it into its own icons and symbologies. Plutonian artifacts have a Möbius Strip quality (like a barber’s pole of energy) such that their meanings oscillate, in a continuous way, from inside their vessel onto its surface. At Pluto, opposite qualities like joy and despair, utopia and apocalypse, grace and brutality—inside and outside—fuse or exchange properties, as they become momentarily indistinguishable. Much too far away to care, Pluto has bigger fish to fry. I am reminded of words that transpersonal intelligence Seth invested in our plane via his medium Jane Roberts: “[T]his dimension [e.g., source realm] nurses your own world, reaching down into your system. These realities are still only those at the edge of the one in which you have your present existence. Far beyond are others, so alien to you that I could not explain them. Yet they are connected with your own life, and they find expression even within the smallest cells of your flesh.”1 That’s Pluto in spades, a deeplying chimera across which Plutonian sigils project a reality too alien for Earthlings to glean, transmit it right down into their DNA as into the quantum states of their planet’s atoms, every particle of dust, grain of sand, and morsel of soil and stone. Even the ordinary Plutonian glob, more than 98 percent nitrogen ice, reinvents itself beyond disclosure of its actual identity or reference point. Science simply doesn’t reach that deep into a higher-dimensional universe; it doesn’t look far enough into the heavens to see Pluto as more than a pip of old Sol-orbiting rock (though of ambiguous enough caliber to be worth quibbling over). Of course, that’s what it is in this dimension or at this astrophysical vibration, but who knows how many dimensions the starry field reflects as it twinkles from an incomprehensibly vaster sky. For these reasons I have re-scripted NASA’s secular Pluto (with its photo op) to go after a more cryptic and numinous object: Body X, bad boy of the Solar System, fluctuating signifier, meta-planetary dweller between planes. Again Seth, this time Seth II, a higher octave, speaks: “We do not understand the nature of the reality you are creating, even though the seeds were given to you by us. We respect it and revere it. Do not let the weak sounds of this voice confuse you. The strength behind it would form the world as you know it and sustain it for centuries.”2 Do not be confused by Pluto’s minute size, remote location, pallid signal, and demotion to a dwarf. Honor the mystery instead. It is creating our reality, even this nanosecond. Meta-Pluto stands for our cardinal node and cosmic key. By its dual existence it expresses our split emanation: self and cosmos. In a realm beyond our understanding, it is generating the zodiac, the starry heavens, and the terms for this world. It is pulling souls into the current universe. This anthology provides the rubric and premise of that proposition. I had been tracking the New Horizons saga since the mission was announced in 2001, at the time replacing the earlier Pluto Fast Flyby as well as its more sophisticated successor, the Pluto Kuiper Express, neither of which was ever built or launched. Both of them would have reached Pluto by now, or well before the planet had traveled so far toward aphelion (its farthest point from the Sun) that its gauze-thin atmosphere froze out, i.e., crystallized and dropped to the ground in colorless snow. That process, creeping along an icy, electrostatic lattice day by day, will have wiped any remaining film from the crisp, starry Plutonian night by 2020. (The Earth’s atmosphere freezing out, by the way, would mean millennial blizzards depositing miles-high glaciers and icebergs on an airless terrain, then a gigantic white star exploding out of a black sky across a blinding snowpack of dunes covering mountains, valleys, seas, and plains.) Each mission (Flyby and Express) was canceled, in turn, for lack of funding, to be replaced by a more efficient concept. Finally, after an intense political battle, NASA got a Pluto line-item approved; hired subcontractors to fashion, program, and forge a metal bird for deployment; and fired the robot into space on a flight plan delivering it pretty much nonstop to where Pluto, traveling in its own eccentric orbit, would cross its path 3,464 days later give or take a fortnight. NASA’s unmanned interplanetary space program took shape in the early sixties with Mariner’s missions to Mars and Venus. During the heyday of Solar System reconnaissance (from roughly 1979 through a smidgen into the aughts), probes visited Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and their moons, plus the asteroid Vesta (2011) and various other asteroids and comets. They and hardware from several space agencies—those of the Soviet Union, China, the European Union, Japan, and India—flew by, orbited, and imaged the Moon, and the two planets closer to the Sun than Earth, Mercury and Venus, usually as part of the same mission by using a slingshot effect from Venus to get to Mercury. The United States’s Pioneer 10 passed within eighty-one thousand miles of Jupiter in 1973, inaugurating a series of ever closer encounters with the region’s largest planet—Jupiter is an ideal slingshot for accelerating probes to worlds beyond it too. Pioneer 11 conducted the first flyby of Saturn in 1979, and two Voyager probes soon followed it there. The second, Voyager 2, was slung into a pre-programmed trajectory by Saturn’s gravitational field so that it intercepted Uranus in 1986 and, after being redirected by Uranian gravity, met Neptune on its ellipse in 1989. Soon after Mariner 4 reached Mars, the United States and Soviet Union began parachuting satellites onto Venus (1966). In 1995 the United States sent a probe from the Galileo orbiter onto Jupiter where it collected fifty-eight minutes worth of data on exospheric and thermospheric composition, temperature, radiation, band instabilities, and weather while traveling at about thirty miles per second. Before it could sink any further, it succumbed to local ambient pressure exceeding twenty-three Earth atmospheres as well as a meteor-like 307 degrees Fahrenheit. En route to Jupiter, Galileo became the first artificial human object to visit an asteroid (Gaspra) and then the first to detect an asteroidal moon (Dactyl circling Ida). Ten years later NASA programmed the Huygens vehicle to separate from its Cassini spacecraft and land in the Xanadu region of Saturn’s moon Titan. It settled on a high-albedo elevated plain that had multiple channels running through it. In November 2014, the European Space Agency separated the Philae probe from its Rosetta spacecraft and bounced it onto the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, the first human touchdown on a bolide. Launched in March 2004 from French Guiana, Philae preceded New Horizons into space by more than a year. And, of course, humans traveled to and walked on the Moon multiple times during the U.S. Apollo program, the first such manned touchdown in 1969. Only Pluto was missing. It was too out-of-the-way, negligible, and asteroid-like to merit a detour by Voyager 2 after “Grand Tour” stops at Uranus and Neptune and their moons. On its way to the Kuiper Belt and beyond, Voyager didn’t even consider Pluto—its Earthbound programmers didn’t. Their more exigent priorities were to measure the dwindling influence of the Sun to heliopause, to taste the interstellar medium, and to carry a plaque into Deep Space bearing humankind’s message to the universe. Plus the puny ninth planet wasn’t deemed worth the cost of sending a tailor-made payload otherwise. However, after another decade of scientific advancement, a surprising recognition took hold: the one missing orb was accessible by new, relatively inexpensive technology. Blueprints for Pluto flybys graduated