Pious Nietzsche: Decadence and Dionysian Faith PDF

Preview Pious Nietzsche: Decadence and Dionysian Faith

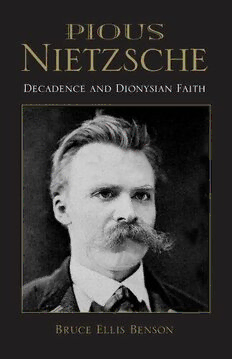

Philosophy Religion Pious Bruce Benson has turned Bruce Ellis Benson puts forward the surpris- Benson Nietzsche out a provocative and major ing idea that Nietzsche was never a godless study of nietzsche, present- nihilist, but was instead deeply religious. But ing nothing less than the how does Nietzsche affirm life and faith in the prayers of tears of Friedrich midst of decadence and decay? Benson looks nietzsche.This ground- carefully at Nietzsche’s life history and views breaking work, which dem- onstrates the deeply religious of three decadents, Socrates, Wagner, and Paul, Decadence and Dionysian Faith character of nietzsche as a to come to grips with his pietistic turn. Key to new religiosity that issues this understanding is Benson’s interpretation from his critique of the reli- of the powerful effect that Nietzsche thinks gion that he had inherited, P music has on the human spirit. Benson claims will make us think again i that Nietzsche’s improvisations at the piano about nietzsche no less than o were emblematic of the Dionysian or frenzied, about religion. —John D. Caputo ecstatic state he sought,but was ultimately un- u able to achieve, before he descended into mad- s Benson clearly formulates ness. For its insights into questions of faith, what even the most perspica- decadence, and transcendence, this book is an n cious readers only vaguely important contribution to Nietzsche studies, suspected: the subterra- i philosophy, and religion. nean link between Paul and e nietzsche.not only was t nietzsche’s life-asserting BrucE ElliS BENSoN is Professor and z stance deeply Paulinian, Paul chair of the Philosophy Department at Whea- s himself, in his violent appeal ton college. He is author of Graven Ideolo- to love beyond law, was a c gies: Nietzsche,Derrida, and Marion on Mod- nietzschean avant la lettre. ern Idolatryand The Improvisation of Musical h nothing will be the same in Dialogue: A Phenomenology of Music. He is Paul studies and in nietzsche e editor (with Kevin Vanhoozer and James K. studies after Benson’s explo- sive short-circuit between A. Smith) of Hermeneutics at the Crossroads two opposed traditions. (available from indiana university Press). —SlavoJ ŽiŽek Indiana series in the Philosophy of Religion Merold Westphal, editor INDIANA University Press cover illustration: Friedrich Bruce Ellis Benson Bloomington & Indianapolis Nietzsche, 1875. Photo by INDIANA F. Hartmann, Basel. c. Klassik http://iupress.indiana.edu StiftungWeimar, Goethe-Schiller- 1-800-842-6796 Archiv, GSA 101/17. Pious Nietzsche INDIANA SERIES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION Merold Westphal, general editor Pious Nietzsche Decadence and Dionysian Faith BRUCE ELLIS BENSON Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404–3797 USA http://iupress.indiana.edu Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2008 by Bruce Ellis Benson All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Benson, Bruce Ellis, date Pious Nietzsche : decadence and Dionysian faith / Bruce Ellis Benson. p. cm. — (Indiana series in the philosophy of religion) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-253-34964-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-253-21874-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, 1844–1900. 2. Religion. I. Title. B3318.R4B46 2008 193—dc22 2007021396 1 2 3 4 5 13 12 11 10 09 08 CONTENTS Preface: Reading Nietzsche vii Acknowledgments xvii List of Abbreviations xix Introduction: Improvising Pietism 3 PART 1 From Christian Pietism to Dionysian Pietism ONE The Prayers and Tears of Young Fritz 15 TWO The Euthanasia of Christianity 27 THREE The Piety of Zarathustra 41 PART 2 Profiles in Decadence FOUR Nietzsche’s Decadence 55 FIVE Socrates’ Fate 79 SIX Wagner’s Redemption 97 SEVEN Paul’s Revenge 119 PART 3 Nietzsche’s New Pietism EIGHT Deconstructing the Redeemer 141 NINE Nietzsche’s Musical Askêsis 165 TEN We, Too, Are Still Pious 189 Notes 217 Works Cited 249 Index 261 v PREFACE: READING NIETZSCHE If you should come round to writing about me . . . be sensible enough—as nobody has been till now—to characterize me, to “describe”—but not to “evaluate.” This gives a pleasant neu- trality: it seems to me that in this way one can put aside one’s own passionate emphasis, and that it offers all the more to the more subtle minds. I have never been characterized, either as a psychologist, or as a writer (including poet), or as the inventor of a new kind of pessimism (a Dionysian pessimism, born of strength, which takes pleasure in seizing the problem of existence by the horns), or as an Immoralist (the highest form, till now, of “intellectual rectitude,” which is permitted to treat morality as an illusion, having itself become instinct and inevitability).1 S o Nietzsche writes—near the end of his productive life—provid- ing his own guidelines for interpreting him. It is clear that he des- perately wants to be interpreted in certain ways—as psychologist, writer, poet, inventor of Dionysian pessimism, and immoralist. But, more than that, he wants to be interpreted by someone who has set “one’s own passionate emphasis” aside. Presumably, then, the ideal Nietzsche interpreter is a cool, detached observer, one who only describes and thus keeps herself out of the picture. Indeed, this idea of proper interpretation fits well with Nietzsche’s own worries about how he has been received so far: “This is, in the end, my ordinary experience and, if you will, the orig- inality of my experience. Whoever thought he had understood something of me, had made himself something out of me after his own image—not uncommonly an antithesis to me; for example, an ‘idealist’—and whoever had understood nothing of me, denied that I need be considered at all” (EH “Books” 1; KSA 6:300). Tracy B. Strong quotes the first part of this passage and then goes on to say: “I take this warning seriously.”2 Certainly it is a warning. But does not Nietzsche provide us with one of the most difficult cases of interpretation? Can we even speak of a “right” interpretation of Nietzsche, on the basis of what Nietzsche himself says? Should our quest be one of finding/explicating the “real” Nietzsche or should that quest be something else? vii PREFACE The Quest for the Historical Nietzsche For at least the past half-century3—beginning with Walter Kaufmann’s Herculean efforts to rescue Nietzsche from various sorts of strange inter- pretations and uses—there has been a remarkable attempt to get clear as to what Nietzsche really did say, as well as what those sayings could pos- sibly mean.4 That such an effort was needed stems from myriad aspects: the intentional and unintentional lack of clarity in Nietzsche’s texts, the “holding hostage” of Nietzsche’s writings by his cunning but philosophi- cally challenged sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the use of Nietzsche for Nazi propaganda, and the ways in which Nietzsche’s thought chal- lenged (and continues to challenge) not just the conclusions of most phi- losophers but the very philosophical enterprise and its basic logical prem- ises.5 No better example could be given of this sort of project than the title of the text What Nietzsche Really Said, an illuminating popular book by two highly respected Nietzsche scholars.6 The efforts of Nietzsche scholars over the past fifty years have yielded exemplary Nietzschean scholarship that has clarified much of what can be clarified. Today we are far from the situation of needing to “rescue” Nietzsche. Or are we? Even today the interpreter of Nietzsche is faced with at least four significant complications, ones that concern not just our posi- tion vis-à-vis Nietzsche but also Nietzsche’s own views. First, Emmanuel Levinas has made many of us aware of the conceptual violence that is seemingly endemic to the very hermeneutical enterprise.7 I take Levinas’s concern seriously. To encounter Nietzsche is to encounter an “other” that (to speak with Hans-Georg Gadamer) “breaks into my ego-centeredness and gives me something to understand.”8 Yet it may be safe to say that any interpretation of Nietzsche—simply because it’s an interpretation—ends up doing at least some sort of conceptual violence to Nietzsche’s thought. Although Gadamer at one point insists that, in reading a text, the inter- preter “disappears—and the text speaks,”9 such is never the case. The text may indeed speak, but the interpreter never disappears—for the interpreter is the very possibility condition for the text to speak at all. No texts come to us “uninterpreted.” A second complication is Nietzsche’s own so-called perspectivism and his criticism of the “true world.” Here the problem is not merely one of sifting through the extant texts that seem at times contradictory or viii PREFACE incoherent with the goal of discovering the real Nietzsche. Even if there were something analogous to the “Jesus Seminar” (a “Nietzsche Seminar” perhaps) to give a final pronouncement (deciding, say, once and for all that Nietzsche really was a Polish noble [EH “Wise” 3; KSA 6:628] and identifying which fragments of the Nachlass truly represent his “final” thinking), such a pronouncement would be at odds with Nietzsche’s own thought. If Nietzsche is right in denying the existence of the “true world” (TI IV; KSA 6:80–81), then claims to “perspectives” of what we might call the “true Nietzsche” become problematic. Certainly any pretension to having the ultimate perspective on Nietzsche—whether defined as Platonic eidos or Kantian noumenon—would be self-defeating, since such a claim would be profoundly un-Nietzschean. But the problem cuts more deeply than that. For Nietzsche’s stated view actually undercuts itself. If there are only “perspectives” and no “true” Nietzsche, then Nietzsche neither has any privileged perspective on “himself” nor can he continue to speak in such terms. There are only interpretations of interpretations, traces of traces. Despite that, most interpretations of Nietzsche at least imply that they are giving us a perspective of the “true Nietzsche,” and the usual implication is that this particular perspective is somehow closer to the “true Nietzsche.” Moreover, Nietzsche himself seems to be seek- ing after what we might call “the highest possible perspective.” In other words, Nietzsche is not simply a perspectival relativist who judges all per- spectives of equal validity. Even for Nietzsche, then, some perspectives are better than others. Better? In what way better? There are at least two ways of answering that question. On the one hand, some perspectives are better in the sense that they promote life. Living by certain perspectives, for Nietzsche, simply brings about a better quality of life. On the other hand, some perspectives are more “true.” This leads us to a third aspect of Nietzsche interpretation. That Nietzsche interpreters find it so difficult to leave behind the quest for the historical Nietzsche demonstrates that we clearly have not left the correspondence theory of truth behind (something that Nietzsche’s account would seem to suggest we do). For the notion of the “true Nietzsche” still functions (to use a term of Edmund Husserl’s) as a kind of idea “in the Kantian sense,”10 a regulative ideal toward which to strive. And it’s hard to imagine any text of Nietzschean scholarship without that goal (even if a more minimal sort). When we say that certain interpretations of Nietzsche are more “true,” we do not mean that in ix