Photography and Germany PDF

Preview Photography and Germany

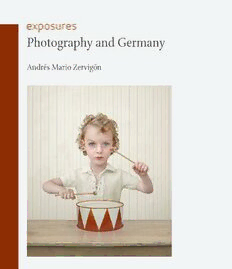

Photography and Germany exposures is a series of books on photography designed to explore the rich history of the medium from thematic perspectives. Each title presents a striking collection of images and an engaging, accessible text that offers intriguing insights into a specific theme or subject. Series editors: Mark Haworth-Booth and Peter Hamilton Also published Photography and Africa Erin Haney Photography and Anthropology Christopher Pinney Photography and Archaeology Frederick N. Bohrer Photography and Australia Helen Ennis Photography and China Claire Roberts Photography and Cinema David Campany Photography and Death Audrey Linkman Photography and Egypt Maria Golia Photography and Exploration James R. Ryan Photography and Flight Denis Cosgrove and William L. Fox Photography and Germany Andrés Mario Zervigón Photography and Humour Louis Kaplan Photography and Ireland Justin Carville Photography and Italy Maria Antonella Pelizzari Photography and Japan Karen Fraser Photography and Literature François Brunet Photography and Science Kelley Wilder Photography and Spirit John Harvey Photography and Tibet Clare Harris Photography and Travel Graham Smith Photography and the USA Mick Gidley Photography and Germany Andrés Mario Zervigón reaktion books Published by Reaktion Books Ltd Unit 32, Waterside 44–48 Wharf Road London n1 7ux, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2017 Copyright © Andrés Mario Zervigón 2017 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 748 0 Contents Introduction 7 one Belated Photography, 1839–1870 11 two Photography and Nation, 1871–1918 47 three The Weimar Era and Photo-consciousness, 1919–1932 83 four The Alluring Surface, 1933–1945 121 five History, the Future and Photography, 1946–1989 155 six Photographic Promiscuity, 1990–2016 189 References 207 Select Bibliography 212 Acknowledgements 214 Photo Acknowledgements 215 Index 217 Introduction In early May 1997, an ambitious and long-anticipated show opened at the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany. Titled Deutsche Fotografie. Macht eines Mediums 1870–1970 (German Photography: Power of a Medium, 1870–1970), it strove for an encyclopaedic history of the country’s photography using key framing questions such as ‘what is a national history of photography?’ and ‘does such a thing as German photography reflect a German mentality?’1 The answers were provisional and the coverage of this enquiry was limited to the hundred years that followed unification in 1871, thereby missing the breathless march of history around the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall. But up to this exhibition and thereafter, no institution has attempted to chronicle the longer histories of photography that can be associated with the country or otherwise categorized as German. This book attempts just such coverage by critically enquiring once more into the relationship between photography and Germany. For many observers, the idea of photography in Central Europe evokes pioneering modernist pictures from the Weimar era or colossal digital prints that define the medium’s art practice today. For others, it recalls horrifying documents of wartime atrocity. Photography and Germany seeks to broaden these perceptions by examining the medium’s multifaceted relationship with Germany’s turbulent cultural, political and social history. It shows how many of the same phenomena that helped generate the country’s most recognizable photographs also led to a range of lesser-known pictures that similarly documented or negotiated Germany’s cultural identity and historical ruptures. The book rethinks 1 Charles-David Winter, View of Strasbourg, c. 1862, albumen print. the photography we commonly associate with the country by discussing 7 the wider sea of emulsion it navigates and the historical context that gives it deeper meaning. Photography and Germany correspondingly covers over 175 years of pictures, beginning with pre-photographic experiments in the light-sensitive chemicals that made the medium’s origins possible, and ending with the tension between analogue and digital technologies that have stimulated the country’s famous contemporary art photography. In these nearly two centuries, Germany played a central role in some of modern history’s most significant events. It also accomplished a harried transition from a loose confederacy of near-feudal agricultural states to an industrialized, modern world power that unified itself not once but twice. This transformation included two revolutions, two world wars, the rise and fall of fascism, an unparalleled genocide and the redivided country’s ‘economic miracle’ under the shadow of Cold War tensions. Photography has been inextricably linked to these events, both as a token of modernity itself and a means of documenting or even intervening in their unfolding. As this book aims to establish, the history of photography in Germany is the history of the country’s troubled encounter with modernity, realized in visual form. The underlying premise of this investigation is that there is little that can convincingly define a body of photography as German. Individual photog raphers and movements may have produced prints that share aesthetic values which were realized in other art forms from the country, such as a twentieth-century focus on technological subject matter that mirrors the country’s famous industrial and graphic design. But it is impractical to suggest an essential German style for a medium that has been used so promiscuously across fields as diverse as science, advertising, journalism and the fine arts, areas of practice where German-based photog- raphers have excelled. Similar uses of the medium in other parts of the world also mean that no one quality can be isolated as distinctly German. For example, the country’s Pictorialist photography may have boasted the brooding character of Wagnerian opera or German fin-de-siècle literature and painting. However, similar melancholy prints were also produced at the time by members of the Stieglitz circle of American photographers. It is therefore just as difficult to designate a distinctly German photography 8 as it is to define German identity as a whole.