Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows PDF

Preview Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows

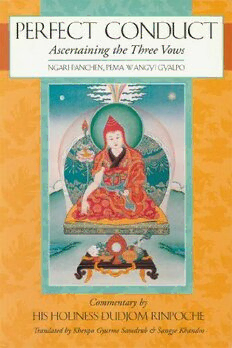

PER.FECT CONDUCT Ascertaining the Three Vows Commentary by HI HOLINE DUDJOM RJNPOCHE Translated by Khenpo Gyurme Sam drub & Sangye Khandro PERFECT CONDUCT Ascertaining the Three UJws NGARI PANCHEN, PEMA WANGVI GVALPO Commentary by HIS HOLINESS 0UDJOM RINPOCHE, ]!GORAL YESHE DORJE Translated by I<.HENPO GVURME SAMDRUB AND SANGYE I<.HANDRO Wisdom Publications • Boston WISDOM PUBLICATIONS 361 Newbury Street Boston, Massachusetts 02115 USA © Sangye Khandro 1996 All rights reserved. No part of rhis book may be reproduced in any form or by aJty means, t:lecuonic or mcch:tnical, induding photocopying. recording, or by any inform2tion storage and retrieval system or tedtnologies now known or later devdoped, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mna'-ris Pa!f-chen Padma-dban-rgyal, 1487 or 8-1542 or 3. [Sdom gsum rnam nes. English] Perfect conduct: ascertaining the three vows I Ngari Panchen Perna Wangyi Gyalpo ; with commentary by Dudjom Rinpoche Jigdral Yeshe Dorje ; translated by Khenpo Gyurme Samdrub and Sangye Khandro. p. em. ISBN 0-86171-083-5 (alk. paper) 1. Trisarp.vara (Buddhism)-Early works to 1800. 2. Vows (Buddhism)-Early works to 1800. 3. Buddhism-Discipline-Early works to 1800. I. Bdud-'joms 'Jigs-bral-ye-ses-rdo-rje, 1904- . II. Gyurme Samdrub, Khenpo. III. Khandro, Sangye. IV Title. BQ6135.M5713 1996 294.3'444-dc20 96-20917 0 86171 083 5 01 00 99 98 97 6 5 4 3 2 Designed by: LJSAWLit' Cover: thangka painting of Ngari Panchen Pema Wangyi Gyalpo by Kunzang Dorje; photograph courtesy of Pacific Region Yeshe Nyingpo. Wisdom Publications' books are primed on acid-free paper and mcer the guidelines for permanence :tnd durabiliry of rhc Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the: Council on Libr:~.ry R~ourccs. Primed in the United States of America. CONTENTS Preface vzz Introduction xv Translator's Note xzx THE COMMENTARY, INCLUDING THE ROOT TEXT 1 First: The Initial Virtue 3 Second: The Intermediate Virtue 7 Chapter One: A BriefE xplanation oft he Stages oft he Main Teaching 7 Chapter Two: An Explanation oft he Priitimok!a-vinaya 14 Chapter Three: The Bodhisattva Vows 63 Chapter Four: Secret Mantra I 00 Chapter Five: An Explanation ofH ow to Practice the Three Vows Together without Conflict 141 Third: The Concluding Virtue 149 Commentator's Note 153 TRANSLATION OF THE ROOT TEXT, ASCERTAINING THE THREE VOWS 155 OUTLINE OF THE COMMENTARY 175 Notes 191 v PUGLISHER.'S ACKNOWLEDGMENT The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous help of the Hershey Family Foundation in sponsoring the production of this book. PF(EFACE Commitment, as the essence of the Buddhist vows, demonstrates the dedication of one's life to refraining from harmful deeds and to fostering peace and joy in oneself and others. These aims are accomplished by disciplining the mind, which is the key to all spiritual actions, ,experiences, and attainments. Lord Buddha said: Not committing any evil deeds, fostering all that is virtuous, and taming one's own mind are the teachings of the Buddha. Buddhist discipline begins with taming the mind, because the mind is the source of all mental events and physical actions. If a person's mind is open, peaceful, and kind, all his or her thoughts and efforts will benefit self and others. If a person's mind is selfish and violent, all his or her thoughts and physical actions will mani fest as harmful. Lord Buddha said: Mind is the main factor and forerunner of all (actions). If with a cruel mind one speaks or acts, misery follows, just as the cart follows (the horse) ... If with a pure mind one speaks or acts, happiness follows, as the shadow never departs. Although the mind is the main factor, for those whose spiritual strength is limited, the physical discipline of living in solitary peace and refraining from indulgence in violent actions is crucial. Mental attitudes and concepts are formed by habits that are totally conditioned by physical and external circumstances and are enslaved by those circumstances. We cannot think, act, or function independently of them. Physical disciplines protect us from becoming prey to the so-called sources of emotions, such as enmity, beauty, ugliness, wealth, power, and fame, which give the mind a craving and aggressive nature, resulting in harmful physical reactions. Thus, physical discipline is an essential means of avoidance and a mechanism of defense. In order to refrain from committing any negative deed, one must persistently follow the guideline of physical and mental disciplines. There are different sets of disciplines in Buddhism, especially in tantra, but their classification into three vows is universal in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. For the Nyingma school of VII Vlll PEIUECT CONDUCT Tibetan Buddhism, Ascertaining the Three Vows (sDom-gSum rNam-Nges) by Panchen Perna Wangyal (1487-1542) ofNgari province has for centuries been the root text for learning the codes of the three vows. In this text, the author elucidates each vow together with its history,. nature, and divisions: how to receive the vow, how to observe the vow, how to repair a broken vow, and the result of observing the vow. The three vows are the vows of priitimokfa, bodhisattva, and tantra. The priitimokfa vow: The vow of pratimokp (individual liberation) mainly emphasizes disciplining one's physical behavior and not harming others. Pratimok~a discipline is called the foundation of Buddhism, because for ordinary people physical discipline is the beginning of spiritual training and the basis of spiritual progress. The aspiration of the pure pratimok~a discipline is the achievement of liberation for oneself, as it belongs to the friivaka training. However, since Tibetan Buddhists are automatically followers of the Mahayana, they emphasize taking the pratimo~a vows with the attitude of bodhicitta. Thus, the vows are taken and observed so that all beings may know happiness and achieve enlightenment. In pratimo~a there are eight precept categories. The upaviisika observes eight vows for twenty-four hours. The upiisaka (male lay householder) and upiisikii (female lay householder) observe five precepts. These three are the precept categories for lay householders. The friimal}era (male novice) and friimal,lerikii (female novice) observe ten, thirteen, or thirty-six vows. The sikfamtina (female novice in training) observes twelve vows in addition to the precepts of a srimat].erika. The bhikfU (fully ordained monk) observes 253 vows, and the bhikfUl}i (fully ordained nun) observes 364 vows. These five are the precept categories for those who are celibate and have renounced the lifestyle of lay householders. In Tibetan monas.tic practice, the last seven .pratimo~a categories are taken for the duration of one's life. Some do not count the upavasika vow as a pratimo~a category since it is a temporary precept. In essence, the training in observing the pratimo~a vow is to avoid any cause for negative action, which is the source of mental affiiction and of pain for oneself and others. In this way, the chain of negative causes and habits is broken, establishing a spiritual basis, which is the source of peace, joy, and benefit for oneself and all parent sentient beings. It is important to remember that unless we can improve our own life, step by step, we will not be properly equipped to be a perfect tool for bringing true joy to others. As long as one's mind is weak and attracted to the sources of emotions, it will be easily influenced or overwhelmed by anger, lust, and confusion. Thus, it is most important to hold back from the sources of emotions by observing the pratimo~a vows. For example, if we are weak, it is wiser not to confront powerful enemies but to avoid them. The pratimok§a vows are a way to defend ourselves from encountering the mental afflictions or their sources. These vows are easy to observe, because they are apparent as physical disciplines such as refraining from killing and stealing. Then, when one's mind is strong enough to stand on its own P~R.F~CT CONDUCT IX with less influence from physical activities or external influences, one can put more emphasis on the disciplines of the bodhisattva. The bodhisattva vow: The vow of the bodhisattva (adherent of enlightenment) mainly emphasizes observing bodhicitta, or the mind of enlightenment. Bodhicitta is the mental attitude of taking responsibility for bringing happiness and enlightenment to all beings, with love and compassion free from any trace of selfish interest, as well as putting this into practice.! So here we are not just refraining from harming others, but dedicating ourselves to serving them. The bodhisattva precept has three major divisions. The first is "refraining from harmful deeds," which has two traditions. According to the tradition of Nagarjuna, there are eighteen major precepts to observe. According to the tradition of Asatiga, for the vows of aspirational bodhicitta, there are four general precepts for not losing the vows and eight precepts for not forgetting them. For the vow of practical bodhicitta, there are four root downfalls and forty-six auxiliary faults from which to refrain. The second division is "the amassing of virtuous deeds." This is the training in the six perfections: generosity, moral discipline, patience, diligence, contem plation, and wisdom. The third division is "the service of others." This is the practice of the four means of gathering or bringing others to Dharma. These four are the practice of generosity, pleasing speech, leading others to the meaningful path of Dharma, and remaining oneself on the same path. According to Longchen Rabjam,2 the vow for the bodhicitta of aspiration is to contemplate the four immeasurable attitudes: love, compassion, joy, and equa nimity. The vow for the bodhicitta of practice is to train in the six perfections. The bodhisattva vow should be maintained until one reaches enlightenment. Unless we abandon bodhicitta, it will remain in us through death and birth, pain and joy. Its force of merit increases in us, even in sleep or distraction, as trees grow even in the darkness of night. Here, people might have a problem with the concept of maintaining the vows after death. According to Buddhism, physical attributes such as body, wealth, and friends will not accompany us into our next lives; but mental habits, convictions, strengths, and aspirations-together· with their effects, their kanna-will stay with us until they are ripened or destroyed. So if we make powerful aspirations and efforts, the vows will remain with us and will form the course of our future lives. The bodhisattva vow is much harder to observe than the vow of pratimok~a, as its main discipline is maintaining the right mental attitude and understanding, which is subtle and difficult to control. However, it is also more powerful and beneficial, since if we have bodhicitta in our mind, we cannot do anything harmful to anyone and can only be of benefit. This is not a matter of avoiding mental afflictions or their sources, but of destroying or neutralizing them. For example, a compassionate attitude pacifies anger, seeing the impermanent nai:ure X PERFECT CONDUCT of phenomenal existence ~lleviates desire, and realizing the causation and/or absence of a "self" ends ignorance. When an aspirant with true bodhicitta aware ness is exceptionally intelligent and diligent, full of energy and enthusiasm, and totally open and appreciative, then he or she qualifies to enter and put more emphasis on the disciplines of tantra. The tantric vow: The vow of tantra (esoteric continuum) mainly emphasizes real izing and perfecting the union of wisdom and skillful means and accomplishing simultaneously the goal of oneself and others. Tantric training begins with receiving empowerment (abhi!eka) from a highly qualified tantric master. In the transmission of the empowerment, the master's enlightened power causes the disciple's innate primordial wisdom nature to awaken, which is the meaning of empowerment. Such wisdom, although inherent in every being, remains hidden like a treasure buried in the walls. With the power of awakened wisdom one trains in the two stages of tantra, the development stage and perfection stage, and accomplishes the goal: the attainment of buddhahood for the benefit of oneself and others. In order to preserve, develop, and perfect such awakened wisdom, one must observe the samayas (esoteric precepts), as these are the heart of tantric training. Breaking tantric samaya is more harmful than breaking other vows. It is like falling from an airplane compared to falling from a horse. Tantric realization and transmission are full of power, depth, and greatness. There is no way of giving up tantric vows except to break them and fall. For tantric samaya there are numerous precepts to observe, but Ngari Panchen presents the main ones. These include the precepts of twenty-five esoteric activities, the five buddha families, the fourteen root downfalls, and the eight auxiliary down ~alls of tantra in general. In addition, he presents the twenty-seven root downfalls and twenty-five auxiliary precepts unique to the vehicle of the Great Perfection. Without taking and maintaining samaya, there is no way of accomplishing any tantric attainments. Lord Buddha said:3 For those who have impaired the samaya, the Buddha never said that they could accomplish tantra. Je Tsongkhapa writes:4 Those who claim to be practicing tantra without observing the samaya have strayed from it, since in anuttara tantra it is said, "The tanna will never be accomplished by those who do not observe samaya, who have not received proper empowerments, and who do not know the suchness (the meaning of empower ment, the wisdom), even though they practice it." The three vows are steps that lead to the same goal, enlightenment. The stream