Passport to Peking: A Very British Mission to Mao's China PDF

Preview Passport to Peking: A Very British Mission to Mao's China

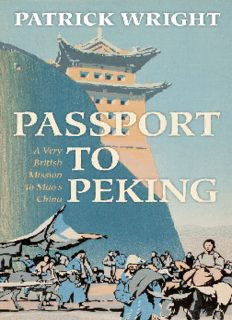

PASSPORT TO PEKING Frontispiece: Paul Hogarth, Man and Cart, China, 1954, conté. Passport to Peking A VERY BRITISH MISSION TO MAO’S CHINA PATRICK WRIGHT 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Patrick Wright 2010 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress Control Number: 2010933105 Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc ISBN 978-0-19-954193-5 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 My empire is made of the stuff of crystals, its molecules arranged in a perfect pattern. Amid the surge of the elements, a splendid hard diamond takes shape, an immense, faceted, transparent mountain. Why do your travel impressions stop at disappointing appearances, never catching this implacable process? Why do you linger over inessential melancholies? Why do you hide from the emperor the grandeur of his destiny?’ Kublai Khan to Marco Polo, Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (1972) In comparing an alien culture with one’s own, one is forced to ask oneself questions more fundamental than any that usually arise in regard to home affairs. One is forced to ask: What are the things that I ultimately value? What would make me judge one sort of society more desirable than another sort? What sort of ends should I most wish to see realized in the world? Bertrand Russell, The Problem of China (1922) What was the good of going to Peking when it was just like Shrewsbury? Why return to Shrewsbury when it would all be like Peking? Men seldom moved their bodies; all unrest was concentrated in the soul. E. M. Forster, ‘The Machine Stops’ (1909) If you’ve ever been part of an offi cial delegation, you learn less about a country than sitting in the British Museum and reading about it. Joe Slovo, New York Times, 4 December 1994 Say! When’s this guy going to get to China? Stanley Spencer, speaking to the Bourne End Parents Association, 1957 To Claire Preface and Acknowledgements Stanley Spencer was a peculiarly home-loving artist. So closely did he cleave to the Berkshire village of Cookham that he once feared he might have damaged his vision irreparably just by walking a few miles along the Thames to fulfi l a commission in neigh- bouring Bourne End. What, then, was he doing drawing and painting in the People’s Republic of China? I fi rst pondered this question in 2001, when working as a curator of Tate Britain’s exhibition of Spencer’s paintings and drawings.1 Looking further into the matter, I found that Spencer had trav- elled in September 1954 as an invited guest of the Communist-led government in Peking. Far from being alone in his unexpected journey to the Orient, he went along with several planeloads of Britons gathered in from various sometimes very loosely defi ned positions on the left of the political spectrum. A group from the Labour Party leadership fl ew fi rst, including the former Prime Minister Clement Attlee and his Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan. A party of dissenting ‘Bevanite’ Labour MPs departed later, packed together, not always happily, with a clutch of their more right-wing and pro-American colleagues. The fl ight over Eastern Europe, Soviet Russia, and Mongolia was also undertaken by a strangely mixed company of scientists and artists, architects and writers. Various trade unionists and local councillors embarked, and so too did the national secretary of the Women’s Co-operative Guilds of Great Britain. There were liberal-minded sceptics aboard the planes, as well as partisan admirers of the new regime and some allegedly quite ignorant freeloaders too. And all this took place nearly eighteen years before February 1972, when President Richard Nixon and his wife Pat stepped down onto the tarmac at Beijing to commence the visit that is now often assumed to mark the opening of relations between the People’s Republic of China and the West. The occasion for these east-bound fl ights was provided by the fi fth anniversary celebrations of the Communist ‘Liberation’, proclaimed by Mao on 1 October 1949. The invitations, which viii Preface and Acknowledgements were not approved by the elderly Winston Churchill’s Conserva- tive government, followed years of acute international tension. The Iron Curtain, which was fi rst brought down around Commu- nist Russia in 1919/20, had been lowered again very shortly after the Second World War, this time dividing Europe from the Baltic to the Adriatic, as Winston Churchill declared in his famous Fulton oration of 5 March 1946. An Asian extension, a ‘cordon sanitaire’ that was quickly dubbed the ‘Bamboo Curtain’, was placed around Communist China a few years later. These largely impenetrable barriers were never just closed frontiers. They were shored up by opposed and contrary propagandas as well as by censorship, trade embargos, blockading warships, and govern- ments that were learning how to play the game of ‘brinkmanship’ with the threat of nuclear catastrophe. If the post-war decade was a time of ‘containment’ and bloc- building, in which there was much talk about monolithic centres of power and their closely controlled ‘satellites’,2 it also saw new kinds of confl ict. First named by George Orwell in 1945, the ‘Cold War’ had become a prevailing reality in Europe. In Asia, the wars had been altogether hotter, and not just in Korea. As a colonial power, Britain had also been faced with nationalist and Communist insur- gencies in India, Indonesia, Malaya, Burma, and elsewhere. By the summer of 1954, further tensions were being provoked by more recent initiatives, two of which especially had combined to divide the British Labour Party into feuding factions. One was the proposed rearmament of West Germany. The other was the formation of the South-East Asia Treaty Organization, promoted as an Eastern consort to NATO by President Eisenhower’s fi ercely anti-Communist Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and brought into existence when its charter was signed on 8 September 1954. These initiatives were supported by the leadership of the Labour Party, and opposed vigorously by the left of the party, gathered as its Tribune reading members were around the charis- matic fi gure of Aneurin Bevan. The defeat of the Bevanites on both counts was confi rmed at the Labour Party’s annual confer- ence, held in Scarborough at the end of September. At the time of the fl ights to Peking, Britain’s political life was being pressed into the ‘Natopolitan’ mould that would be denounced at the end of the decade by the no longer Communist Preface and Acknowledgements ix historian E. P. Thompson.3 In his view, this forceful manoeuvre had been successfully completed by the General Election of 26 May 1955, which was won by the Conservatives under Anthony Eden after a campaign that was ‘conducted entirely within the political and strategic premises of NATO’.4 Thompson attributed the British people’s compliance with this redefi nition of their possibilities to various causes: apathy, the persistence of attitudes derived from ‘exhausted imperialism’, and the allure of capital- ism’s promise of yet to be delivered ‘affl uence’. Disenchantment with the idea of radical political transformation was also wide- spread, thanks not least to the increasingly unmistakable horrors of Stalinism, which, as Thompson suggested, had also worked to discredit more native radical traditions, which actually had nothing to do with Soviet Communism. Through much of 1954, however, there were many Britons who resisted the drift into ‘Natopolitan’ conformity. The year had opened with encouraging signs of a thaw in the Cold War. Stalin had died in March 1953, and a somewhat more conciliatory atti- tude seemed to be emerging in Moscow. At the end of July an armistice had brought the Korean War to the state of suspension in which it still hangs to this day, and the year had opened with new signs of a possible settlement in Indo-China, where French forces were fi ghting a losing war against Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh. Early in 1954, it emerged that the Chinese Premier Chou En-lai would be leading a Chinese delegation to Geneva, where he would take part in an international conference which, though shunned by America, would consider ways of settling France’s continuing war in Indo-China. The Geneva Conference of 1954 may not feature as much more than a footnote in the Cold War histories of our time. Yet to those who looked on eagerly as the participants struggled their way through various impasses, its fi nal resolution seemed a marvellous return to sanity. Britain’s Conservative Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden was widely praised for his diplomacy. For many, however, the real hero was Chou En-lai, who had proved himself quite unlike the manipulated Soviet puppet of anti-Communist expectation. A mantle of Western admiration and hope settled over the shoul- ders of this handsome Chinese leader, and the invitations to visit China followed before the smiles had time to fade.

Description: