Outlaw Woman: A Memoir of the War Years, 1960–1975, Revised Edition PDF

Preview Outlaw Woman: A Memoir of the War Years, 1960–1975, Revised Edition

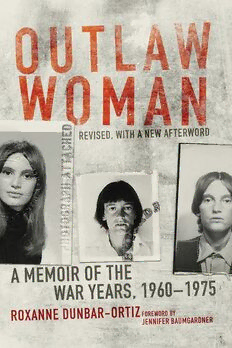

Also by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz Economic Development in American Indian Reservations (ed.) Native American Energy Resources and Development (ed.) Indians of the Americas: Human Rights and Self-Determination La Cuestión Mískita en la Revolución Nicaragüense Indigenous Peoples: A Global Quest for Justice (ed.) e Miskito Indians of Nicaragua: Caught in the Crossfire Blood on the Border: Memoir of the Contra War Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie Roots of Resistance: A History of Land Tenure in New Mexico e Great Sioux Nation: Oral History of the Sioux-United States Treaty of 1868 An Indigenous History of the United States 1 Outlaw Woman A Memoir of the War Years, 1960–1975 By Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz Revised, with a New Aerword Foreword by Jennifer Baumgardner UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS NORMAN 2 2800 Venture Drive Norman, Oklahoma 73069 www.oupress.com Copyright © 2014 by the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Publishing Division of the University. Manufactured in the U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the United States Copyright Act— without the prior permission of the University of Oklahoma Press. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, University of Oklahoma Press, 2800 Venture Drive, Norman, Oklahoma 73069 or email [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-8061-4479-5 (paperback : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8061-4535-8 (ebook : mobipocket) ISBN 978-0-8061-4536-5 (ebook : epub) is eBook was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at [email protected]. 3 In memory of Audrey Rosenthal, 1940–1967, who died in South Aica in the struggle against apartheid and in honor of all those, past and present, committed to creating a just and peaceful world and for the war resisters and deserters, and our political prisoners, who continue to pay the price for our struggles 4 Contents Foreword, by Jennifer Baumgardner Preface to the Revised Edition Prologue: Red Dirt Girl 1. San Francisco Chrysalis 2. Becoming a Scholar 3. Valley of Death 4. 1968 5. Sisterhood in the Time of War 6. Revolution in the Air 7. Cuba Libre 8. Desperada 9. Aer Attica 10. “Indian Country” Aerword 5 Foreword In 1989, I was a sophomore in college in a small midwestern town. A close friend confided in me that she had been raped during her study abroad. at experience provoked a flood of terrible memories of sexual abuse from both of her parents, but mostly cognizance of her cold, intimidating, irritable, and revered father having molested her. As the visions grew more horrific and her anger more intense, I remember telling her that if she killed her father, I’d help her go on the lam. What else could she do? Making this pronouncement, and even imagining the plan, felt far from scary at the time (although it sounds unbelievably risky to me now). It sounded, actually, like the only sane thing to do. What happened to my roommate was beyond comprehension to many people in my life—my parents, most of my friends—but I was beginning to see incest and sexual assault as frighteningly common. Around this time, my older sister began coming to terms with her first sexual experience: being raped by a high school friend at fourteen while she was at a party, drinking for the first time, semiconscious. I was nineteen and waking up to the utter acceptance of violence against women. I was tapping into the power of telling the truth about the things that happen behind closed doors, screaming out the secrets that protect perpetrators and do nothing to help victims. e only way to make a difference in the face of this denial of injustice was to ignore rules, mores, and laws. Also at nineteen, I first fell in love with radical feminist writings like those of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. In fact, I fell in love with activists like her—they were my Jesse Jameses, my Bonnie Parkers, my Pretty Boy Floyds. And yet I found myself stuck in a conflict. I was grateful for the insights and inspiration, but wished I had that culture of mass organizing. Why was I born in the 1970s? e movements I wanted to be a part of had come to a head when I was just learning to walk. I feared I had missed out on traveling a revolutionary path. 6 Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz’s childhood was anything but privileged, her years as a politico anything but timid. But in this book, Outlaw Woman, and in the new aerword Roxanne has written, I encounter her grappling with the myriad ways that a feminist has attempted to construct an ethical, politically coherent life. She writes of reading de Beauvoir’s e Second Sex in 1963: “It was the family . . . the basic unit of patriarchy and male dominance. . . . is was my rationalization for leaving my husband and daughter, certain it was a political move.” Already, you sense in her account the idea that simply leaving her family might not solve the problem of male dominance. e beauty of the book, in addition to its page-turning narrative, is her continual desire to remain self-aware. Each new chapter presents an opportunity to review past choices and understand her own motivations perhaps differently, certainly more deeply. Over the years, I have come to terms with the legacy of the 1960s and 1970s. e deep belief that the world was about to transform into one where women’s liberationists would be in the vanguard and capitalism dismantled didn’t pave the way to that reality. In our present reality, capitalism is bound up in the body of social justice. ere are corporate sponsors, social entrepreneurs, and billionaire men at the forefront of global health, and oen, activists appear lonely, silly, and naïve to try and work totally outside the system—to become an outlaw. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz calls herself an outlaw in this memoir because to abide by the laws of what was an overtly racist, misogynist, anti-gay, anti–human rights America—which is what the radicals of the 1960s confronted—was to be an accomplice. And she was trying to change her personal script: a radical feminist who visited Valerie Solanas aer she shot Warhol, Roxanne also struggled with her attraction to and dependence on domineering men. She writes of herself and her Second Wave peers: “We were all struggling between the deep conditioning we received as females and our newfound feminism.” An outlaw is a deeply attractive identity, even if it ends in bullets and blood. But I’m slowly coming to see that the true revolutionary understands her history, has visions of a better future, and faces (with courage) her own era. is book is a testament to how at least one outlaw 7 woman evolved, struggled, and continued to make change. e story of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz inspires me to find my path, rather than pine for that revolutionary past. I’m grateful to her and to feminists like her for that and for so much more. I show my gratitude by knowing my history, imagining something better, and facing the reality of today. Jennifer Baumgardner September 11, 2013 New York City 8 Preface to the Revised Edition City Lights originally published Outlaw Woman in 2001. I appreciate the two great feminist editors there who worked with me on the book, Elaine Katzenberger and Nancy Peters. Outlaw Woman is my second memoir and follows Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie, which tells the story of my early life and ended with my move to San Francisco in 1960. at book, originally published by Verso, was published in a paperback edition by the University of Oklahoma Press in 2005. I started this book in 1989 in Molly Giles’s weekly writing group and continued it in Diana O’Hehir’s and Sheila Ballantyne’s Mills College writing workshops. I am grateful to those three fine writers and to the other writers—especially the young feminists—in the workshops. During the final year of work on the book, I benefited from Wendy Earl’s careful reading and critique. I appreciate Jean-Louis Brachet, Rob Albritton, and Martin Legassick for keeping my letters and making them available to me. Others— especially Chude Allen, David Barkham, Cathy Cade, Dana Densmore, Darlene Fife, Mary Howell, Elizabeth Martínez, and Lawrence Weiss—as well as those who kept my letters, shared their memories that sometimes conflicted with my own, reminding me not always to trust my first recall but to probe more deeply, and with humility. Many writer friends and colleagues read versions of the book over the decade I was working on it. Ellen Dubois, Elizabeth Martínez, Simon Ortiz, and Mark Rudd read early versions and encouraged me. Sam Green, Chris Crass, and others of the younger generation read later versions and their enthusiasm for the project inspired me. Karen Wald’s keen eye and vast knowledge of the Cuban Revolution helped me with the chapter on Cuba. I used some material from this book in my lectures for my annual women’s studies course at California State University, East Bay, “Women, War, and Revolution,” and the students’ responses were invaluable. 9