Out in culture: gay, lesbian, and queer essays on popular culture PDF

Preview Out in culture: gay, lesbian, and queer essays on popular culture

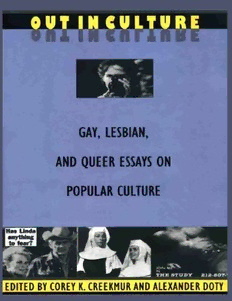

OUT IN CULTURE Gay, Lesbian, and Queer Essays on Popular Culture Edited by Corey K. Creekmur and Alexander Doty Duke University Press Durham and London 1995 3rd printing, 2006 © 1995 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Typeset in Plantin with Gill Sans display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Introduction Responsibilities of a Gay Film Critic Lesbians and Film The Hypothetical Lesbian Heroine in Narrative Feature Film The Great Escape There’s Something Queer Here Supporting Character: The Queer Career of Agnes Moorehead The Ambiguities of “Lesbian” Viewing Pleasure: The (Dis)articulations of Black Widow From Repressive Tolerance to Erotic Liberation: Mädchen in Uniform Acting Like a Man: Masculine Performance in My Darling Clementine Dossier on Hitchcock Hitchcock’s Homophobia The Murderous Gays: Hitchcock’s Homophobia “Crisscross”: Paranoia and Projection in Strangers on a Train “I’m not the sort of person men marry”: Monsters, Queers, and Hitchcock’s Rebecca The Queer Voice in Marnie Flaming Closets Men’s Pornography: Gay vs. Straight Freud’s “Fetishism” and the Lesbian Dildo Debates Tom of Finland: An Appreciation Visible Lesions: Images of the PWA Pee Wee Herman: The Homosexual Subtext “In Living Color”: Toms, Coons, Mammies, Faggots, and Bucks Dossier on Popular Music In Defense of Disco Crossover Dreams: Lesbianism and Popular Music since the 1970s Immaculate Connection The House the Kids Built: The Gay Black Imprint on American Dance Music Children of Paradise: A Brief History of Queens The Politics of Drag Black Macho Revisited: Reflections of a Snap! Queen All Dressed Up, But No Place to Go? Style Wars and the New Lesbianism Commodity Lesbianism Gay, Lesbian, and Queer Popular Culture Bibliography Acknowledgments of Copyright Contributors Index OUT IN CULTURE Edited by Michèle Aina Barale, Jonathan Goldberg, Michael Moon, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick In Memory of Marlon Riggs Introduction Corey K.Creekmur and Alexander Doty Out in Culture charts some of the ways in which lesbians, gays, and queers have understood and negotiated the pleasures and affirmations, as well as the disappointments and denials, of mass culture. As readings that challenge the hegemonic structure of mainstream opinion and representation–what has been called compulsory heterosexuality (Adrienne Rich), the heterosexual matrix (Judith Butler), or the straight mind (Monique Wittig)1–the essays collected here develop antihomophobic and antiheterocentrist critical approaches to some of the major forms of contemporary mass culture: film, television, popular music, and fashion. Homosexual men and women have always had a close and complex relation to mass culture. Historians such as David Halperin, John D’Emilio, and Lillian Faderman have argued, in fact, that the identity that we designate homosexual arose in tandem with capitalist consumer culture.2 But, like all marginalized minorities or (sub)cultures, gays and lesbians often found their cultural experience and participation constrained and proscribed by a dominant culture in which they are a generally ignored or oppressed, if logically integral, part.3 Certainly, gays and lesbians can experience and make meaning of mass culture in ways the culture industries encourage: consuming it “straight” as “just mere” entertainment. Historically, however, gays and lesbians have also related to mass culture differently, through an alternative or negotiated, if not always fully subversive, reception of the products and messages of popular culture–and, of course, by producing popular literature, film, music, television, photography, and fashion within mainstream mass culture industries. As a result, many gay and lesbian popular culture producers and consumers have wondered how they might have access to mainstream culture without denying or losing their oppositional identities, how they might participate without necessarily assimilating, and how they might take pleasure in, and make affirmative meanings out of, experiences and artifacts that they have been told do not offer queer pleasures and meanings. Surrounding concerns like these are general cultural paradigms that have defined gay and lesbian experience, most often through the metaphor of the closet–a private (or “sub”-cultural) space one comes out of to inhabit public space honestly and with one’s identity intact. As Diana Fuss argues, “The philosophical opposition between