Preview Our Heritage Our Future low res

Our Heritage, Our Future The BLM and America’s Public Lands Dedication The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) dedicates this book to all of its employees—past and present. BLM employees serve the American public with enthusiasm, perseverance, creativity, conviction, and commitment, and it is through their vision that future generations will be able to experience, value, and enjoy our treasured public land heritage. Suggested citation: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 2017. Our heritage, our future: The BLM and America’s public lands. Bureau of Land Management, Office of Communications, Washington, DC. Copies available from: Bureau of Land Management National Operations Center Printed Materials Distribution Services Denver Federal Center, Building 50 P.O. Box 25047 Denver, CO 80225 P-267 www.blm.gov/history The mention of company names, trade names, or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the federal government. BLM/WO/GI-18/002+1701 Fort Ord National Monument in California. Acronyms and Abbreviations Contents Foreword __________________________________________________________________ix Chapter 2: AIM Assessment, inventory, and monitoring The Bureau Embraces Ecosystem Management, 1990–2000 _______________________41 Acknowledgments __________________________________________________________xi BLM Bureau of Land Management An Interdisciplinary Approach Guides the Planning Process ___________________41 Ecosystem Management Creates Challenges _______________________________43 Prologue: Management of the Public Domain Evolves, 1776–1976 __________________1 EIS Environmental impact statement A Threatened Species Influences Northwest Forest Management ______________43 Chapter 1: A Forest Summit Leads to the Development of the Northwest Forest Plan _______44 FLPMA Federal Land Policy and Management Act The Federal Land Policy and Management Act Guides the Way, 1976–1990 ___________3 Science and Politics Merge in the Interior Columbia Basin ____________________47 Land Use Planning Enters A New Era _______________________________________3 Rangeland Conditions Improve __________________________________________49 GIS Geographic information system Forest Management Generates Debate ____________________________________7 Fish and Wildlife Habitat Improvements Help Restore Populations _____________51 Range Policy Changes Focus _____________________________________________9 “Riparian–Wetland Initiative for the 1990s” Establishes Restoration Goals ________51 GLO General Land Office Riparian Resource Management Finds Common Ground _____________________10 The War on Weeds Gets Underway _______________________________________54 Fish and Wildlife Inventories Lead to Habitat Protection ______________________12 Abandoned Mine Cleanups Recover Lost Landscapes ________________________54 NEPA National Environmental Policy Act Cultural and Heritage Resources Face Growing Threats _______________________15 “Recreation 2000” Ushers In New Programs and Sites ________________________54 Designated Recreational Areas Increase ___________________________________17 Cultural and Paleontological Resources Comprise the NLCS National Landscape Conservation System The Wilderness Inventory Process Begins __________________________________20 “Great Outdoor Museum” _______________________________________________57 Energy and Minerals Management Focuses on Independence _________________23 The President, Congress, and the Bureau Recognize Special Places _____________61 O&C Oregon and California Public Land Disposal Authority Expands ___________________________________27 The Wild Horse and Burro Program Addresses Controversy____________________63 Congress Provides Law Enforcement Authority _____________________________30 Energy and Minerals Management Considers Environmental Changes __________65 REA Rapid ecoregional assessment Changes Influence Fire and Aviation Management __________________________34 Wildland Fire Management Reaches a Turning Point _________________________68 RMP Resource management plan Wild Horse and Burro Inventories Identify Issues ____________________________38 Congress Passes Realty Management Reforms ______________________________71 The Bureau Develops a Professional Law Enforcement Program ________________71 Notes _______________________________________________________________40 Notes _______________________________________________________________74 Adobe Town Wilderness Study Area in Wyoming. ii Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands iii Featured Stories Chapter 3: Chapter 4: Chapter 1 __________________________________________________________________3 Chapter 2 _________________________________________________________________41 Collaborative Management Helps Address 21st Century Challenges, 2000–2009 _____75 National Concerns Lead the Bureau in a New Direction, 2009–2012 ________________137 The Transforming Effect of the Natural Resources Defense Council Consent Decree Ecosystem Thinking Comes to the Public Lands The Secretary Establishes the National Landscape Conservation System _________75 America Invests in Jobs _______________________________________________137 By D. Dean Bibles _________________________________________________9 By Mike Dombeck _______________________________________________42 Public Lands Experience Record Fire Seasons _______________________________82 Energy and Minerals Programs Undergo Changes __________________________138 Grazing Fees: The Next Generation Creating Options in Western Oregon A National Energy Policy Emerges ________________________________________87 Initiatives Address Climate Change on Public Lands ________________________141 By Judy Nelson __________________________________________________11 By Mike Benefield ________________________________________________44 The President Launches the Healthy Forests Initiative ________________________95 The National Landscape Conservation System Becomes Permanent ___________144 Evolution of a Biologist The Road Less Traveled The Bureau Revises Its Western Oregon Plans ______________________________96 Recreation Demands Continue to Grow __________________________________150 By Tim Carrigan _________________________________________________14 By Gloria Brown _________________________________________________46 The Secretary Announces the Healthy Lands Initiative _______________________97 Partners, Youth, and Volunteers Pitch In __________________________________151 Working Underground for the Bureau of Land Management The Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project Habitat Assessments Take a Landscape Approach ___________________________99 Large-Scale Efforts Require a Strategic Planning Approach ___________________153 By James Goodbar _______________________________________________16 By Cathy Humphrey ______________________________________________48 The Bureau Focuses on Healthy, Sustainable Rangelands ____________________105 Wildlife Habitat Conservation Stretches Across Landscapes __________________153 Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River The First Resource Advisory Council Meeting—The First Broadcast The Wild Horse and Burro Program Reaches a Critical Crossroads ______________107 Fire Policy Allows Management for Multiple Objectives _____________________155 By Theresa Herrera _______________________________________________18 By Chip Calamaio _______________________________________________50 Cultural and Paleontological Resources Take the Spotlight ___________________109 A Task Force Revisits Northwestern Forest Issues ___________________________157 The Battle to Conserve the “Crown Jewels” The Evolution of Aquatic Resource Management in the BLM Recreation Management Focuses on Outcomes ___________________________112 The Rangeland Program Addresses Drought Conditions _____________________158 By Cecil D. Andrus _______________________________________________22 By Mike Crouse __________________________________________________53 The Lands and Realty Program Tackles Challenges _________________________114 The Secretary Develops a New Wild Horse and Burro Strategy ________________158 The Year of Three Agencies The Fortymile National Wild and Scenic River Law Enforcement Collaborates with Local Partners _________________________118 Lands, Realty, and Cadastral Survey Programs Support Bureau Priorities ________160 By Larry Bauer __________________________________________________25 By Gene Ervine __________________________________________________55 A New West Leads to a Renewed Planning Emphasis _______________________123 Law Enforcement Officers Protect Against Resource Damage Northern Futures Leading by Example: Volunteers and Friends Groups The Bureau Develops a 21st Century Workforce ____________________________127 and Threats to Public Safety ____________________________________________165 By Bob Faithful __________________________________________________28 By Dave Hunsaker _______________________________________________56 The Secretary Designates the National System of Public Lands _______________131 Public Lands Provide Economic and Intrinsic Value _________________________166 A Long Tradition of Federal Resource Protection Who Owns Big Al? By Steven Martin ________________________________________________30 By John P. Lee ___________________________________________________57 Notes ______________________________________________________________133 Notes ______________________________________________________________169 The Sagebrush Ceiling The Bisti Beast: The First Paleontological Excavation in BLM Wilderness Epilogue: The Bureau Looks to the Future, 2013 and Beyond _____________________173 By Lynell Schalk _________________________________________________33 By Pat Hester ___________________________________________________58 Firefighting: Then and Now Environmental Education on the Ground: Native Plant Restoration at Appendix: Directors of the Bureau of Land Management ________________________174 By The BLM’s National Interagency Fire Center External Affairs Staff _________36 Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Adoptions Place Mustangs in Good Homes By Beth Kampschror______________________________________________60 Index ____________________________________________________________________177 By Sarah Beckwith _______________________________________________39 Reminiscences of Wilderness and Training Compiled by Jim Foote ____________________________________________62 Managing the BLM’s Helium Program By Leslie A. Theiss ________________________________________________67 From Chains to Lasers and Global Satellites By Robert Casias ________________________________________________70 Continental Divide National Scenic Trail in Colorado. iv Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands v Chapter 3 _________________________________________________________________75 Chapter 4 ________________________________________________________________137 Establishment of the National Landscape Conservation System Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009 From Alaskan Sourdough to Little Miss Sunshine By Tom Fry _____________________________________________________77 By Lucia Kuizon ________________________________________________110 By Linda Resseguie ______________________________________________140 The National Landscape Conservation System Extends to the Subtropics Managing a Modern Day Fossil Bone Rush The BLM Takes a Landscape Approach By Bruce Dawson ________________________________________________79 By Alan L. Titus _________________________________________________111 By Kit Muller and Barry Rose ______________________________________143 Pulling Together to Preserve History Travel Management Is Everyone’s Business Owyhee Canyonlands: A Lesson in Perseverance By Mike Abel ___________________________________________________81 By Mark Goldbach ______________________________________________112 By Robin Fehlau ________________________________________________145 Great Basin Restoration Initiative Shelf Road Climbing Area: The BLM and the Climbing Community Scale the Celebrating Science in the National Landscape Conservation System By Mike Pellant__________________________________________________82 Heights of Partnership By Marietta Eaton ______________________________________________147 Invasive Species Alter Fire Regimes and Fire Operations By Mark Hesse _________________________________________________113 Celebrating the Legacy and Centennial of the Iditarod National Historic Trail By Ken Frederick _________________________________________________84 New Century Brings New Funding for Land Acquisitions By Kevin Keeler _________________________________________________149 Life on a BLM Engine By David Beaver ________________________________________________115 America’s Backyard: The Growth of Outdoor Recreation on BLM Lands By Kari Boyd-Peak _______________________________________________85 Alaska Land Transfer By Bob Ratcliffe and David O. Howell ________________________________151 Milford Flat: Utah’s Largest Fire Rehabilitation Project By Ramona Chinn and Christy Favorite ______________________________116 Technological Changes Enhance Safety, Operations in Wildland Firefighting By Lola Bird ____________________________________________________86 Stones and “Bones” Set by William (Billy) Octavius Owen in Wyoming By Sheri Ascherfeld _____________________________________________156 Powder River Basin Resurveys: 20 years—16,000 Monuments By J.D. “Sam” Drucker ____________________________________________117 Land and Water Conservation Fund Acquisitions By Joel T. Ebner__________________________________________________89 Special Agents Work with Resource Specialists to Uncover Fraud and Theft By David Beaver ________________________________________________162 The Legendary Roan Plateau By Joe Nardinger _______________________________________________119 The Road to Resolution: Revised Statute 2477 By Jamie Connell, with David Boyd __________________________________91 BLM Investigative Work Leads to Arson Convictions By Jeff Holdren _________________________________________________164 Just How Big Is That Right-Of-Way Grant? By Kyle Gandiaga _______________________________________________120 The Value of the BLM’s Wild Side: Western Communities Benefit By Tom Hurshman _______________________________________________93 The BLM Meets the Counterculture at the Burning Man Festival from Open Landscapes The BLM’s Innovative Approaches to Renewable Energy Development in Arizona By Doran Sanchez ______________________________________________122 By Luther Propst ________________________________________________167 By Kathy Pedrick ________________________________________________94 Tribal Consultation Is Democracy Compatible with Conservation? Restore New Mexico: A Model for the Nation By James G. Kenna ______________________________________________126 By Patricia Nelson Limerick _______________________________________168 By Jesse Juen ___________________________________________________98 The Changing Face of the BLM Looking Beyond the Strutting Grounds: Changing the Way the BLM Manages By Melissa Dukes _______________________________________________127 Wildlife Habitat The Maturing of the BLM’s Tribal Relationships By Dale Tribby _________________________________________________100 By Cheryle Cobell Zwang _________________________________________129 Lake Havasu Fisheries Improvement Program 1992–2011 Back to the Future: Changes in the BLM’s Organization in the 21st Century By Lori Cook ___________________________________________________102 By Rebecca Mack and Alexandra Ritchie _____________________________130 The Native Plant Materials Development Program and Seeds of Success A Director’s Perspective: 2007-2009 By Peggy Olwell ________________________________________________104 By James L. Caswell _____________________________________________132 Terror Comes to the High Desert: BLM Wild Horse and Burro Corrals Are Firebombed By Joseph Fontana ______________________________________________108 White Mountains National Recreation Area in Alaska (L and R photos). vi Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands vii Rogue River Ranch National Historic Site in Oregon. Foreword This book highlights the recent history of the being good neighbors and recognizing traditional shifted, and Congress merged the GLO and another BLM and serves as a sequel to “Opportunity and uses of public lands. agency, the U.S. Grazing Service, creating our Challenge: The Story of BLM,” released in 1988. It agency in 1946. reviews significant changes that occurred within We do this through the Federal Land Policy and the agency through 2012 and explains how those Management Act, passed by Congress in 1976. This This book is unique in that it draws largely from the changes affect public lands today. Together, the law enables us to promote multiple uses of public firsthand experiences of current and former BLM two books present a brief history of public land lands so that they may best meet the present and employees. They are not historians, but they have management, from the creation of the General future needs of the American people. lived a specialized history, implementing evolving Land Office (GLO) in 1812 to the 200th anniversary public land management direction and meeting of the GLO in 2012. Applying multiple use management requires broad the late 20th and early 21st century challenges of knowledge and skill. This is because of the breadth multiple use management in the face of increasing While the book recognizes the Bureau’s evolution and diversity of today’s public land resources and demands for public land uses. In short, they are from the GLO, we also consider this work a what they mean to the public. But the BLM has real Americans working to turn public policy into reflection of how well suited the BLM is to considerable experience to rely on. reality on the ground. address the Trump administration’s priorities. This means supporting energy independence You see, the BLM’s roots go back to the early In reading “Our Heritage, Our Future: The BLM through environmentally responsible development; years after America’s independence, when the and America’s Public Lands,” I am confident you promoting conservation through shared young nation began acquiring additional lands. will see that as history has shaped public lands stewardship; making America safe through effective At first, Congress used these lands to encourage and how they are used, our agency has been there border management; promoting jobs on working homesteading and westward migration. To support to meet the opportunities and challenges that landscapes; and serving the American family by this national goal, Congress created the GLO. Over accompany change. time, values and attitudes regarding public lands Michael D. Nedd Acting Deputy Director, Operations Bureau of Land Management Old homestead in Idaho. Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands ix Gooseberry Mesa National Recreation Trail in Utah. Acknowledgments The BLM produced “Our Heritage, Our Future: Derrick Henry, Linda Hill, Dave Hunsaker, The book could not have been written without The BLM and America’s Public Lands” as part of a Jennifer Kapus, Jeff Kitchens, Jeff Krauss, the assistance and contributions of Brian Amme, commemoration of two important anniversaries: Elizabeth Rieben, Mitch Snow, Hans Stuart, Joe Ashor, Shayne Banks, Chip Calamaio, the creation of the General Land Office in 1812 Kyle Sullivan, Twinkle Thompson, and Don Charpio, Glen Collins, Elena Fink, and passage of the Homestead Act of 1862. The Bev Winston. The team is indebted to the book’s Sam Guagush, Rich Hanson, Dave Harmon, BLM and numerous partners launched a variety authors: Derrick Baldwin, Bibi Booth, Elaine Brong, Deborah Harnke, Robin Hawks, Antonia Hedrick, of additional efforts in 2012, including holding Don Buhler, Brianna Candelaria, Bob Casias, Rob Hellie, Sherry Hendren, Doug Herrema, local and national celebrations and symposia, Elena Daly, Randy Eardley, Shelly Fischman, Michael Hildner, Jeff Jarvis, Marilyn Johnson, establishing a history website, and developing an Tony Garrett, Kim Harb, Margaret (Megg) Heath, Barbara Klassen, Jerry Magee, Dick Mayberry, illustrated timeline of major events in the BLM’s Jeff Holdren, Jeff Kitchens, Steve Martin, Dennis McLane, Kim Menning, Ted Milesnick, history. One such partner, the Public Lands Geoff Middaugh, Jeanne Moe, Elizabeth Rieben, Cynthia Moses-Nedd, Kit Muller, Lauren Pidot, Foundation, which is largely comprised of BLM Don Smurthwaite, Mitch Snow, Matt Spangler, Bob Ratcliffe, Deb Rawhouser, Linda Rundell, retirees, provided assistance in developing some of Hans Stuart, Twinkle Thompson, and Deb Salt, Laurie Sedlmayr, Ed Shepard, Tim Spisak, the material included in this book, and many of its Elizabeth (Betsy) Wooster. Tremendous gratitude Bob Stahl, Joe Stout, Andrew Strasfogel, members participated in the events described here. goes to these authors as well as the authors of more Mary Tisdale, Jeanne Van Lancker, Bob Wick, than 200 sidebars for sharing stories that so enrich Davina Wilkins, and Elaine Zielinski. A BLM history team produced the book, the the BLM’s literary landscape and celebrate our website, and other educational products. The public land heritage. team consisted of Celia Boddington, Peter Doran, Basin and Range National Monument in Nevada. Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands xi Immigrants traveling west. Prologue | Management of the Public Domain Evolves, 1776–1976 The Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM’s) story further settlement followed, including the Timber all vacant, unreserved, and unappropriated public began with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, marking Culture Act, Desert Land Act, and Stock Raising lands in the West from entry for other than mineral the end of the Revolutionary War. Great Britain Homestead Act. use so that grazing districts could be set aside and relinquished its claim to the 13 colonies and ceded the remaining public lands classified for their best another 237 million acres of land reaching west to At the beginning of the 20th century, President use. The Department of the the Mississippi River, forming the nation’s original Theodore Roosevelt promoted the idea that land Interior created the Division of “public domain.” In 1785, the United States created and its resources had an inherent worth beyond Grazing, which would later a Land Ordinance that became the basis for the extraction and development. Roosevelt, one of become the Grazing Service, surveying, securing, and selling of all public lands history’s great conservationists, focused on using to administer these into the future. public lands to promote the best and highest use grazing districts. of resources while also considering future From 1803 to 1867, the United States acquired over generations and their needs. During his tenure, In 1946, seeking to relieve a billion acres of land, including Florida, Texas, the President Roosevelt oversaw the creation of tensions over grazing fee President Southwest, the Northwest, and Alaska. To oversee 150 national forests, more than 20 national increases between the Grazing Theodore Roosevelt. the disposition of these lands, Congress established parks and monuments, and 55 bird and wildlife Service and Congress, Secretary the General Land Office (GLO) in the Treasury reserves, leaving a permanent mark on the nation’s of the Interior Harold Ickes Department in 1812. In 1849, the GLO moved to public domain. recommended merging the the newly formed Department of the Interior. Grazing Service with the GLO. With fewer than 200 million acres of vacant public President Harry Truman Between 1850 and the early 1900s, the United States domain remaining by the 1920s, free and open forwarded the proposal to focused on three key areas related to public land land had become a rare commodity for those Congress as part of his management: transportation, resource use and looking to develop large farming or ranching Reorganization Plan No. 3, and extraction, and homesteading. During this period, operations. Furthermore, the land that remained on July 16, 1946, the Grazing President the United States established its first reserves for was often overgrazed. In 1928, Congress authorized Service and the GLO became Franklin Roosevelt. timber and lead. Through land grants for wagon the Mizpah-Pumpkin Creek Grazing District in the BLM. The BLM not only roads and canals in the 1820s, the nation set a Montana, the first grazing district on public lands. inherited the duties of the GLO clear precedent for determining where and how to An association of ranchers leased these lands and and Grazing Service, it also establish infrastructure. In 1862, Congress passed instituted conservative grazing practices. Ranchers incorporated the Alaska Fire the Homestead Act, which opened the floodgate of from across the West soon petitioned for similar Service, various revested lands settlement in the West by giving 160 acres of land grazing reserves in their areas, which led to passage (including the Oregon and to qualified persons who had lived on the land and of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934. After signing California Railroad lands and improved it for 5 years. Other acts encouraging the act, President Franklin Roosevelt withdrew the Coos Bay Wagon Road President A Montana ranch (1872). Harry Truman. Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands 1 lands), and multiple foundation for the agency’s multiple use mission. new policies, programs, and legislation. In its mineral reserves. During the 1950s, the BLM formalized its forestry, 1970 report, “One Third of the Nation’s Land,” the recreation, minerals management, wild horse and Commission recommended that the United States The reorganization plan burro, and wildlife programs. consider retaining most of the public domain. Pompeys Pillar National Monument in Montana. did not provide a clear From the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, Chapter 1 | The Federal Land Policy and Management Act Guides the Way, 1976–1990 mandate or any additional The 1960s brought rapid growth and fundamental Congress passed a host of new laws, including the formalized direction. change to the BLM, permanently altering the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Air Fred Johnson, the first Bureau’s course. President John Kennedy asked the Quality Act, Wild and Free Roaming Horses and The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of Land Use Planning Enters a New Era The BLM began developing this new land use director of the BLM, BLM to accelerate its inventory of the public lands Burros Act, Federal Water Pollution Control Act, BLM Director 1976 was landmark legislation that established the planning system in the late 1970s, incorporating headed an agency of Fred Johnson. and develop a program of balanced use to reconcile Endangered Species Act, and Energy Policy and mission of the Bureau of Land Management along FLPMA represented a fundamental change in FLPMA’s core mandates of multiple use and almost 700 employees, resource conflicts. The agency also began taking Conservation Act, that would change how the with the initial statutory authorities necessary to public attitudes about the management of the sustained yield of resources. This new system built most of them having worked for the GLO in the on its first conservation-focused lands in the form BLM did business. However, none of these would advance that mission. FLPMA merged the many nation’s public lands. For the first time, Congress upon the BLM’s management framework plans of Washington Office. Just 86 employees oversaw of wild and scenic rivers and national scenic and match the Federal Land Policy and Management disparate public interests and values of the public stated that America’s public lands comprised the 1960s, eventually replacing them with resource 150 million acres of grazing land. By 1948, historic trails. Act (FLPMA) of 1976, the BLM’s Organic Act, for lands into one unified mission of “multiple use and nationally significant resources and recommended management plans (RMPs).1 Over the next several continued controversy led to major budget cuts for the change it would bring to the agency. FLPMA sustained yield.” retaining them in public ownership. decades, the BLM continually refined and improved the agency, reducing staff by more than half and In 1964, Congress established the Public Land Law (pronounced flip-ma) formally recognized what the its land use planning process and adapted it to a barely funding most programs. Review Commission to study the nation’s 3,000 BLM had been doing for many years: managing the The policy embodied in FLPMA reflected an This new policy sparked an era of comprehensive changing West and a changing world. land laws and federal management of the public public lands under the principles of multiple use evolution that had already begun within the land use planning in the BLM that In 1948, Secretary of the Interior J.A. Krug named domain to identify problems and recommend and sustained yield. BLM and one that continues today—a holistic guided future management of the Marion Clawson as the BLM’s second director. perspective of the land that recognizes the public domain for the benefit of the Clawson reorganized the BLM and laid the interdependence of resources and the necessity of American people. FLPMA mandated using scientific and interdisciplinary methods to that the Secretary of the Interior, manage them. through the BLM, conduct land use planning using a “systematic interdisciplinary approach, to achieve integrated consideration of physical, biological, economic, and other sciences” in support of multiple use, which it defined in part as “harmonious and coordinated management of the various resources,” and sustained yield principles. An important requirement was that the BLM coordinate with other federal agencies and state, local, and tribal governments and involve the public in developing the new land use plans. BLM range conservationists working in the Poncha Pass Resource President Conservation Area south of Salida, Colorado (1962). John Kennedy. Timber sale on public lands in Wyoming (1965). 2 Prologue | 1776 –1976 Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands 3 Planning Ties to Other Federal Land Policy lands are in a real sense our last frontier. We uses and environmental values. This challenge The California Desert Becomes California Desert Conservation Area. and Management Act Requirements cannot afford to squander their riches.”2 was noted as early as 1970 by the Public Land a Planning Showcase Law Review Commission, which recommended Over the next 40 years, the BLM designated nearly that Congress “establish firm preferences among Among the specific land use directives included To enhance the BLM’s management and 1,000 areas of critical environmental concern, uses” or “establish statutory standards reflecting in FLPMA was a provision calling for the creation decisionmaking capability, FLPMA directed that protecting important characteristics and values of value judgments as to the prevailing importance of the California Desert Conservation Area. the Bureau “prepare and maintain on a continuing more than 20 million acres of public lands. of various broad objectives served by the public Managing nearly 11 million acres of public lands in basis an inventory of all public lands and their lands.” However, neither Commission members the southern California desert area had become a resource and other values” and that “this inventory Additionally, FLPMA directed the BLM to “take nor Congress could agree on how to accomplish singular challenge for the BLM. Public use of these shall be kept current so as to reflect changes in any action necessary to prevent unnecessary this ordering of user preferences or prioritizing of desert lands had rapidly increased over the years, conditions and to identify new and emerging or undue degradation of the lands.” The BLM public lands values. In the end, the BLM used its along with competition among user groups and resource and other values.” The BLM expanded its applied this standard of “undue degradation” on own discretion in making such determinations. degradation of the desert ecosystem. existing inventory efforts to comply with FLPMA’s authorizations in all of its program areas. The more demanding requirement to catalog and FLPMA’s directive for a “comprehensive long- broad discretion provided by this standard allowed The BLM made critical decisions for allocating quantify rangelands, fish and wildlife habitat, range plan” for the area launched one of the most the BLM to restrict certain uses, such as the the land’s resources at the land use planning stage. mineral and archaeological resources, recreational extensive planning efforts ever undertaken by the development of mining claims or mineral leases, “Land use planning is the backbone of the BLM, opportunities, lands with wilderness characteristics, BLM. The Bureau hired more than 60 planners to protect land and other resources. The authority the blueprint for everything we do,” said Elaine and other values on the public lands. and resource specialists and dedicated millions was strengthened a year later by the Surface Mining Zielinski, a former BLM state director for Oregon of dollars to extensive resource inventories, Control and Reclamation Act, which authorized the and Arizona. “It’s the arena where the public and FLPMA also required the BLM to recognize and monitoring, and regular revisions. The BLM Secretary of the Interior to designate certain federal organizations have the most impact on how public manage areas of critical environmental concern designed the California Desert Conservation lands as unsuitable for coal mining operations. lands are managed.” Planning decisions identified and to give priority to designation through the Area plan to be dynamic and adaptable. The the activities and foreseeable development planning process. FLPMA defined these areas as result became a showcase for the BLM’s resource In FLPMA, Congress also stated its policy that allowed, restricted, or excluded for all or a part of public lands where special management attention management planning efforts. The BLM had “the public lands be managed in a manner which the planning area over the life of the plan. More is required to protect historic, cultural, or scenic succeeded in meeting all of Congress’ requirements recognizes the Nation’s need for domestic sources extensive resource inventories and monitoring data values; fish and wildlife resources; and other natural with a plan that balanced the diverse public of minerals, food, timber, and fiber from the public helped the BLM make more informed decisions but systems. Furthermore, FLPMA allowed the BLM to demands and needs. lands.” Fulfilling its multiple use and sustained did not necessarily make the decisions any easier. designate areas of critical environmental concern yield mission required the BLM to balance the Nor did they enable managers to avoid controversy to protect life and safety from natural hazards that It soon became clear, however, that the Bureau need for these commodities with other land when making hard choices. require management action. could not replicate the level and intensity of effort devoted to the California Desert Conservation Area Grazing on reclaimed land in Colstrip, Montana (1975). In testimony given to the House of Representatives plan for other plans. Nevertheless, the BLM carried in 1971, Secretary of the Interior Rogers C.B. many components forward in its planning system, Morton stated: such as inventory and monitoring, the use of early geographic information system (GIS) technology, “The identification of the most critical and the creation of an automated system to collect environmental areas will be given a high information. The BLM piloted new programs, such priority by this Department so that those as wilderness and visual resource management, in areas may be given the protection they so the California desert planning process that became urgently need. . . . The national resource models for adoption Bureauwide. 4 Chapter 1 | 1976–1990 Our Heritage, Our Future | The BLM and America’s Public Lands 5

The list of books you might like

$100m Offers

The Strength In Our Scars

Rich Dad Poor Dad

Believe Me

Queen Takes Rose

Busardo 2 Anabolic-MS_CN

Genesia Les Chroniques Pourpres 4 La Derniere Prophetesse

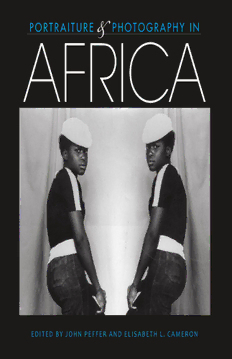

Portraiture and Photography in Africa

Banda Larga no Brasil : passado, presente e futuro

Greek Government Gazette: Part 1, 2008 no. 31

NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) 20100017776: Results and Analysis from Space Suit Joint Torque Testing

Extraordinary Gazette of India, 2009, No. 107

DTIC ADA567650: Al/CuxO/Cu Memristive Devices: Fabrication, Characterization, and Modeling

DTIC ADA484047: Changing Homeland Security: Teaching the Core

Full Circle Magazine FR

Invertebrate Palaeontology & Evolution

SHORT COMMUNICATION. A new combination and a new subsection in Crepidium (Orchidaceae)

Vascular Flora of Isla del Coco, Costa Rica