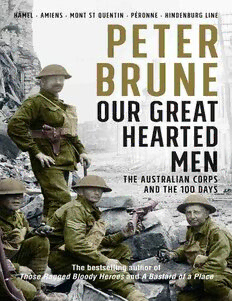

Our Great Hearted Men PDF

Preview Our Great Hearted Men

Contents List of Maps Chapter 1 Michael Chapter 2 Sharpening the tools Chapter 3 An enormous intellect Chapter 4 The physical audacity Chapter 5 . . . so I drove over them Chapter 6 . . . the finest fighting day I have yet had Chapter 7 . . . the enemy’s inevitable reaction Chapter 8 Our horses hated it and whimpered Chapter 9 . . . an ignorant, wonderful lot of fools Chapter 10 . . . a stunning achievement Chapter 11 . . . some damn good men amongst them Chapter 12 . . . one dead man to every 2 yards of trench Chapter 13 The equal of any Chapter 14 . . . great-hearted men Photo Section Acknowledgements Bibliography Appendix I: Classification of BEF Field Artillery Appendix II: Conference of 31st July, 1918 Appendix III: Letter, Bean to White, 28 June 1918 Abbreviations Endnotes Index About the Author Copyright List of Maps The Western Front, March 1918 Operation Michael Hamel, 4 July 1918 Battle of Amiens, 8 August 1918 Amiens, 9–11 August 1918 The Pursuit, 22–29 August 1918 Frontal Attack, 29 August 1918 Mont St Quentin, 31 August 1918 Mont St Quentin—Péronne, 1 September 1918 Mont St Quentin—Péronne, 1–5 September 1918 The Hindenburg Line The Outpost Line Attack, 18 September 1918 The Hindenburg Line, 29 September 1918 The Australian Corps—Ground Captured CHAPTER 1 Michael L ieutenant George Mitchell, 48th Battalion, Saturday 23 March 1918: Order to prepare to move. I stand in the sun. A stout, old Frenchman sows his field, broadcasting steadily up and down. All with us is activity. What matter the personal shock of combat to him. I anticipate it all. The roar of shells, the wounds, the stink of explosives, and the eternal yabbering of machine guns. The farmer 1 steadily goes on with his sowing. We go to the reaping. By March 1918 Lieutenant George Mitchell and many veterans of the First AIF had, during a succession of bloody and costly battles, confronted their ‘reaping’ for nearly three devastating years. Mitchell, and many like him, had despaired of their chances of seeing home again. And yet as volunteers they had a quiet, resigned acceptance of their fate: England is England . . . I want something that I have not got . . . The return to Australia is unreal, and, after all, do we really desire to go back without the laurel crowning of Victory? Better death than final defeat . . . You may never know what home is unless you pay the price of the learning . . . Great battles that we fought through are forgotten in the stormy host. Our pals went under. ‘And the old days never will come again.’ . . . New battles came. We lived. Yet more battles. We still live. And the future holds visions of more and more strife . . . We will meet our fates with good grace, for it is written in 2 the Book of Eternity. As Mitchell left for the front on 23 March 1918, he was destined to face a part of the final major German offensive of the war—and a near calamity. He could not have contemplated that later, within a mere 100 days, the Allies would turn a desperate defence of the British Expeditionary Force’s (BEF) very survival on the Western Front into a comprehensive victory. This is the story of arguably the First AIF’s finest hour—five elite divisions together at last as a united corps, under its own experienced, astute leadership and commanded by an Australian general whose considerable appreciation of the science of war, coupled with studied innovation, an understanding of logistics, and minute planning, would prove brilliant. *** At the onset of the winter of 1917–18, as both sides considered the future of the Great War, one concept, embodied in one word, dominated their thoughts—manpower. Since late August 1916 General Erich Ludendorff had, as Field Marshal Hindenburg’s Chief of Staff, exerted the prime influence upon the German conduct of the war. Tall, red-faced, with cropped hair and a monocle, and possessing a heavy physique, Ludendorff had a typical Prussian officer appearance that belied his humble background: he had not risen through the ranks by the accident of birth or the cultivation of influence, but by hard work and merit. On 11 November 1917 at a conference at Mons, Ludendorff had to make a critical decision. Although Russia had been knocked out of the war and German troops and equipment were being rapidly transferred to the Western Front at a rate of some two divisions a week, that encouraging news was counter-balanced by a number of grim realities: 1917 had seen 3 the German Army suffer over 1 million killed; the strategy of unrestricted submarine warfare had failed, and failed to such an extent that it had brought the United States into the war; and the ongoing British blockade of Germany had been far more effective, and had resulted in acute food and fuel shortages that were undermining morale at home, and as a consequence, political discontent and strikes were becoming more prevalent. Time was the key. Ludendorff understood that other than the injection of divisions currently arriving from Russia to the Western Front, his only other source of manpower would be those males reaching military age in 1918. Late in 1917 Ludendorff had possessed around 150 divisions against the Allies’ 175. By March 1918, using his divisions arriving from the Eastern Front, he anticipated that he could deploy 192 divisions to the 4 Allies’ 173 on the Western Front. Any German offensive in 1918 would therefore have to be delivered in the spring, before the American build-up of troops would eventually overpower his army. This sudden and rapid accumulation of German troops would facilitate one, and only one, substantial offensive—there would be no second chances. Knowing that he could now concentrate his force, and having determined the timing of the offensive, Ludendorff was then faced with a key strategic and tactical challenge. He had always considered the British to be the ‘driving force of the 5 Entente, and the offensive must therefore be directed against them’. Thus, three plans to attack the BEF were examined: the first was against its junction with the French near the German-occupied town of St Quentin (codenamed Michael); the second was at Arras (codenamed Mars); and the third envisaged an attack in the Ypres area to the north (codenamed George). Despite differing opinions of some members of both his staff and those commanders about to undertake the operation, Ludendorff chose Michael, because he rightly believed that this was where the British front was stretched, undermanned and therefore most vulnerable, and that the ground on which that operation was to be fought might dry out quicker than the other two options. His strategic aim was to break through the British front, swing in a north-westerly direction and either destroy the BEF in battle or force its evacuation to the Channel ports. He ordered plans for all three alternatives to be made, so as to conceal his intention from the British, but also to facilitate other options should the operation become stalled. If, by Great War standards, Operation Michael was an ambitious strategic plan, its tactical execution would fly in the face of all previous doctrine—of either side. Ludendorff’s choice of his three army commanders was astute. In the north, General Otto von Below and his Seventeenth Army were tasked with the capture of Bapaume; in the centre General von Marwitz’s Second Army was to capture Péronne; and General von Hutier’s Eighteenth Army was to penetrate the British line at St Quentin, capture the town of Ham, and then provide flank protection as von Below and von Marwitz’s armies thrust right (towards the north-west). All three had earnt Ludendorff’s trust: von Below had served under him in 1914 and had—among other notable successes—only a month before the conference at Mons, been the victor against the Italians at Caporetto (October–November 1917); von Marwitz had planned and executed the brilliant counter-attack against the British at Cambrai; and von Hutier, after a most impressive Western Front record, had further enhanced his reputation with the capture of Riga on the Eastern Front (3 September 1917). Thus, all three German Army commanders possessed not only sound long-term records, but highly impressive recent ones.