On Hashish PDF

Preview On Hashish

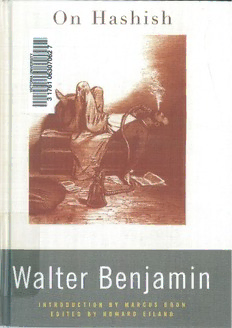

On Hashish - On Hashish Walter Benjamin Translated by Howard Eiland and Others WITH AN INTRODUCTORY ESSAY BY MARCUS BOON scanned by Daniel LeBlanc THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2006 Copyright© 2006 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Additional copyright notices and the Library of Congress cataloging-in-publication data appear on pages 181-183, which constitute an extension of the copyright page. ,, Contents Translator's Foreword vu Abbreviations and a Note on the Texts xiu "Walter Benjamin and Drug Literature," by Marcus Boon 1 Editorial Note, by Tillman Rexroth 13 Protocols of Drug Experiments (1-12) 17 Completed Texts "Myslovice-Braunschwei Marseilles" g-- I05 "Hashish in Marseilles" n7 Addenda From 129 One-Way Street From "Surrealism" 132 From "May-June 1931" 135 From 136 The Arcades Project From the Notebooks 142 From the Letters 144 ''An Experiment by Walter Benjamin," by Jean Selz 147 Notes 159 Index 171 Translator's Foreword THE DRUG EXPERIMENTS documented in this volume took place in the years 1927 to 1934 in Berlin,M arseilles,a nd Ibiza.A long with Walter Benjamin, the participants included, at various times, the philosopher Ernst Bloch,t he writer Jean Selz,t he physicians Ernst Joel, Fritz Frankel, and Egon Wissing, and Egon's wife Gert Wissing.O riginally recruited as a test subject by Joel and Frankel, who were doing research on narcotics,B enjamin experimented with several different drugs: he ate hashish,s moked opium,a nd allowed himself to be injected subcutaneously with mescaline and the opiate eucodal.R ecords of the experiments-they were very loosely orga nized-were kept in the form of drug "protocols." Some of these ac counts were written down in the course of the experiments,w hile ' others seem to have been compiled afterward on the basis of notes and personal recollection.B enjamin also took hashish in solitude,a s witness the three accounts of an intoxicated evening in Marseilles. He took these drugs,w hich he looked on as "poison, "for the sake of the knowledge to be gained from their use.A s he said to his friend Gershom Scholem in a letter ofJanuary 30,1 928," The notes I made [concerning the first two experiments with hashish] ...m ay well turn out to be a very worthwhile supplement to my philosophical ob servations,w ith which they are most intimately related,a s are to a vii Translator's Foreword certain extent even my experiences under the influence of the drug." As an initiation into what he called "profane illumination," the drug experiments were part of his lifelong effort to broaden the concept of experience. During those last years of the Weimar Republic, Benjamin was meditating a book on hashish-a "truly exceptional" study, he tells Scholem-which, however, remained unrealized, and which he came to consider one of his large-scale defeats. No doubt this book would have differed from the loose collection of drug protocols and fe uille ton pieces published posthumously in 1972 under the title Uber Haschisch, and reprinted in 1985, slightly emended and expanded, in Volume 6 of Benjamin's Gesammelte Schriften (Collected Writ ings), source of the present translation. Although we have nothing to indicate specific plans in this regard, it is tempting to think of the drug protocols as a detailed blueprint for the construction of the projected volume; despite their fragmentary character, they artic ulate the gamut of motifs with which the book might well have been concerned. They are in fact highly readable texts, those by Benjamin's colleagues-in which he is described and quoted-no less than his own, and their documentary notebook quality is not un related to the "literary montage" of some of Benjamin's more im portant later works, such as The Arcades Project (into which he incor porated passages from the protocols) and "Central Park." The notational style, moreover, is a reflection of the discontinuous and as it were pointillistic character of the drug experiences themselves, which Benjamin likens to a "toe dance of reason." The philosophical immersion that intoxicants afforded Walter Benjamin was not Symbolist derangement of the senses, then, but Vitt