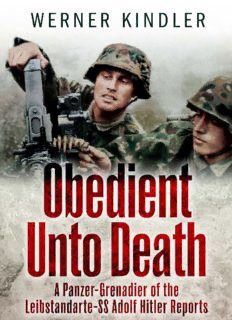

Obedient Unto Death: A Panzer-Grenadier of the Leibstandarte: SS Adolf Hitler Reports PDF

Preview Obedient Unto Death: A Panzer-Grenadier of the Leibstandarte: SS Adolf Hitler Reports

Originally published in German in 2010 as Mit Goldener Nahkampfspange Werner Kindler – Ein Panzergrenadier der Leibstandarte. This English edition first published in 2014 by Frontline Books an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS www.frontline-books.com Copyright © Munin Verlag Deutsche Buchunion GmbH Translation copyright © Frontline Books, 2014 Foreword copyright © Frontline Books, 2014 HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-84832-734-4 PDF ISBN: 978-1-47383-667-9 EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47383-491-0 PRC ISBN: 978-1-47383-579-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library For more information on our books, please visit www.frontline-books.com, email [email protected] or write to us at the above address. Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Typeset and designed by M.A.T.S. Leigh-on-Sea, Essex Contents List of Plates Foreword by Charles Messenger Preface and Translator’s Notes Introduction Chapter 1 From a Farm in Danzig into the Leibstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler Chapter 2 Russia 1941–1942: My First Ten Close-combat Days Chapter 3 I Become a Panzer Grenadier Chapter 4 The Battle for Kharkov, 27 January–29 March 1943 Chapter 5 The Seizure of Byelgorod, 18 March 1943 Chapter 6 Interlude and Preparations for Kursk, 29 March–4 July 1943 Chapter 7 Operation Citadel – the Kursk Offensive Chapter 8 12 July 1943 – The Death Ride of the Soviet Tanks at Prochorovka Chapter 9 The Leibstandarte in Italy, 5 August–24 October 1943 Chapter 10 Back to the Eastern Front, 15–30 November 1943 Chapter 11 Operation Advent and the Fighting in the USSR to March 1944 Chapter 12 The Reorganisation in Flanders, April to June 1944 Chapter 13 Invasion: Securing the Mouth of the Scheldt, 6–17 June 1944 Chapter 14 Action in Normandy, 30 June–20 August 1944 Chapter 15 Tilly-la-Campagne, Caen and Falaise to the Westwall: 25 July–November 1944 Chapter 16 The Führer-Escort Company, the Gold Clasp and Preparing for the Ardennes Chapter 17 The Ardennes Offensive, 16–24 December 1944 Chapter 18 Transfer to Hungary, January–February 1945 Chapter 19 Operation South Wind, 17–24 February 1945, and the Retreat from Hungary Chapter 20 The Fighting on Reich Soil, 1 April–8 May 1945 Notes List of Plates The author. A visit to the house of Hitler’s parents at Leonding near Linz, winter 1940. Units of 4th SS-Totenkopf Standarte parade through a Dutch town, autumn 1940. The author’s No 19 (MG) Company, LAH in 1941. SS-Captain Heinz Kling, commander No 18 Company LAH, 1941. Peiper issuing his final instructions from an APC before an attack. Company commanders and the Battalion adjutant. The APC battalion in winter with the new MG 42. The APC battalion often launched night attacks in Russia. Panzer grenadiers of the Battalion preparing for a counter-attack. Karl Menne of No 12 Company. Kharkov, March 1943. 12 March 1943. APCs of No 11 Company in Kharkov. Panzer grenadiers in an APC near Mk IV panzers of the LAH. SS-Corporal Hannes Duffert on a tank-gun APC of No 14 Company. Men in an APC watch a direct hit close by. Jochen Peiper decorates a young panzer grenadier during the Kursk offensive. The author’s company commander at Kursk. An APC with a 3.7cm anti-tank gun. The author’s Grille in Italy, August 1943. Awards of the Iron Cross First Class on 16 September 1943 in Italy. Fritz Schuster of No 12 Company. The APC battalion marching through Reggio-Emilia. SS-Leading Grenadier Werner Kindler. The Iron Cross First Class; the Close-combat Clasp in silver; the Wound Badge in gold. Awards of the Close-combat Clasp in silver for service on the Eastern Front. Training on the new APCs delivered before the invasion. In Bree, Belgian Flanders, before the invasion. In July 1944 the author’s platoon was equipped with six APCs armed with 7.5cm guns. Foreword T here is no doubt that Werner Kindler was a very brave soldier and was probably very lucky to survive the war. He was also clearly a dedicated member of the Waffen-SS and appears to have retained his Nazi views throughout his life. True, Kindler had cause to be hostile towards the Poles. His family lived in the so-called Polish Corridor, which Germany had had to surrender to newly independent Poland after the First World War, and, as ethnic Germans, suffered. He therefore welcomed the German invasion of Poland. He then found himself in the SS Totenkopf, with whom he did his military training before joining the Leibstandarte, which had originally been formed as Hitler’s personal guard. He entered Russia with it at the beginning of July 1941 and remained with the division until the very end of the war. Three spells on the Eastern Front, northern Italy over the time of the Italian surrender to the Allies, Normandy, the Ardennes counteroffensive, Hungary, and finally Austria provided the author with a wealth of combat experience. Kindler claims that Hitler launched a ‘preventive war’ against the USSR because it was poised to strike at Germany and cites an article in Pravda of June 2001 and a book by Viktor Suvorov, nom de plume of Vladimir Rezun, a Soviet army officer who defected to the West in 1978. Rezun wrote a number of books claiming that Stalin intended to attack and was supported by a number of German and Russian historians. It was, however, a total myth in that, largely as a result of Stalin’s purges, the Soviet Armed Forces were in no fit state to launch any form of attack and were still undergoing drastic reforms resulting from their poor showing against the Finns during the winter of 1939–40. Their posture in June 1941 was solely defensive.1 When we get on to the actual fighting and what it was like, Kindler says little about his own feelings and experiences. The only aspect that he does recount in detail is the medals and other awards that he earned. In particular, he details every day that counted towards his Close-combat Badge. It is difficult not to believe that he was what the British called in the Second World War a ‘gong hunter’, although he does also recount the awards won by his comrades. Otherwise, the book is more a history of his battalion, 3rd Battalion, 2nd SS-Panzer Grenadier Regiment, which he calls the APC Battalion. His ultimate hero is its commanding officer, Jochen Peiper, who time and again displayed extraordinary leadership and tactical flair, qualities which he would take with him when he was promoted to command 1st SS-Panzer Regiment, also in the Leibstandarte and under which Kindler’s battalion often fought. What is revealing is the author’s views on general aspects of the war. The Russians are guilty of atrocities against German soldiers, but there is no mention of those perpetrated by the Waffen-SS and the German Army. He has little regard for Germany’s enemies, except perhaps the Western Allies’ air power, but Allied bomber crews are dubbed ‘terrorists’. Unconditional Surrender meant the adoption of the Morgenthau Plan, which aimed to strip Germany of all its industry. This, indeed, was Allied policy until more realistic measures were adopted at the July 1945 Potsdam Conference and the German propaganda machine made much of it during the last months of the war. Kindler, however, goes one further, claiming that the intention was also to literally emasculate the German male population. When it comes to the December 1944 Ardennes counteroffensive and, in particular, the Malmédy Massacre, he claims that Peiper and his men were forced to make false confessions. As for himself, he was not at the scene since his sub-unit was providing security for the battle group’s supply echelon. As to who did carry out the murder of the US soldiers, Kindler offers no explanation. Finally, he noted that morale plummeted when Hitler’s death was announced. What then to make of this book? Some will view Kindler as an arrogant and cold-blooded warrior, who delighted in combat. Others may consider him as a man displaying intense loyalty to his country. What his writing does reveal, however, is something of the mind-set of the Waffen-SS soldier, whose fighting spirit was largely forged from the very close bonds which existed among his officers and their men, bonds much closer than those in the Army. Add in National Socialist indoctrination and one begins to understand what motivated them to continue to fight with the same intensity long after the prospect of ultimate victory had vanished.

Description: