Notturno PDF

Preview Notturno

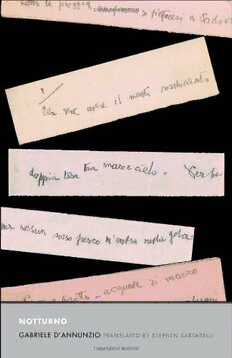

Notturno This page intentionally left blank Notturno GABRIELE D’ANNUNZIO TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED BY STEPHEN SARTARELLI PREFACE BY VIRGINIA JEWISS E YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN & LONDON A MARGELLOS WORLD REPUBLIC OF LETTERS BOOK The Margellos World Republic of Letters is dedicated to making literary works from around the globe available in English through translation. It brings to the English-speaking world the work of leading poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, and playwrights from Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to stimulate international discourse and creative exchange. Notturno originally published in 1921 by Fratelli Treves, Milan. Translation copyright ∫ 2011 by Stephen Sartarelli and Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Set in Electra type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc., Orwigsburg, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data D’Annunzio, Gabriele, 1863–1938. Notturno / Gabriele D’Annunzio ; translated and annotated by Stephen Sartarelli ; preface by Virginia Jewiss. p. cm. -- (Margellos world republic of letters) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-300-15542-6 (cloth : alk. paper) I. Sartarelli, Stephen, 1954– II. Title. PQ4803.N6513 2012 853%.8--dc23 2011042667 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Preface by Virginia Jewiss vii Note on the Translation xiii Notturno First Offering 3 Second Offering 63 Third Offering 191 Post Scriptum 289 Appendix 307 Notes 311 This page intentionally left blank PREFACE by Virginia Jewiss Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Notturno offers one of the most extraordi- nary stories of literary creation ever conceived. On January 16, 1916, D’Annunzio’s plane, a flying-boat on a wartime propaganda mission over Trieste, was forced to make an emergency landing, and D’Annunzio suffered a detached retina in his right eye. In an effort to protect his remaining good eye, his doctors ordered him to remain immobile, both eyes bandaged, in a dark room in his house in Venice. Confined to bed and blackness during the damp Venetian winter, Italy’s most celebrated living author neverthe- less insisted on writing. To keep his sentences from overlapping and running together, he invented a ‘‘new art,’’ or rather, revived an ancient one: ‘‘Then I remembered the way the Sibyls used to write their brief auguries on leaves scattered by the winds of fate.’’ D’Annunzio recorded his own brief thoughts not on leaves but on thin strips of paper, each wide enough for just one or two lines of writing, which his daughter Renata, whom he affectionately called Sirenetta, prepared for him. Following his three-month convalescence, the thousands of scraps of paper he’d filled were gathered and revised, again with the help of Renata, and pub- lished in book form in November 1921. D’Annunzio chose the vii viii Preface evocative title Notturno, a musical and artistic term that conveys both the dreamlike, pensive quality of the work and the disturbing darkness in the author’s soul. Unlike the ancient Sibyls or blind prophets who peer into the future, D’Annunzio used his blindness as a prism through which to view his past hopes and present despair. Burdened with grief for his comrades and guilt for his infirmity, he ‘‘sees’’ in the recesses of his deadened eye man’s ravaged flesh and enduring soul, and he describes death—in all its grotesque glory—with unflinching cold- ness and heartfelt longing. Fragments of his past surface and re- shape themselves in his imagination: the loss of comrades, his mother’s embrace, summers by the sea, travels in Egypt, walks in mist-enshrouded Venice, fiery Rome, and his home town of Pes- cara. Notturno is a diary of darkness and light, a labyrinthine jour- ney through time as memory, fantasy, and hallucination blur in the searing pain of his eye. In a tone that oscillates between leth- argy and zeal, he promotes his self-styled myth of the poet as hero, casting himself as a Nietzschean Übermensch, yet simultaneously revealing his doubts and fears. D’Annunzio agonizes over his own living death of inaction—he compares his narrow bed to a coffin— in contrast to what he considers to be the glorious fates of his fallen comrades, all while fanning hopes of redemption for himself and his country. The work is divided into three ‘‘offerings,’’ and the patriotic and spiritual notions of sacrifice suggested by that term gather force as D’Annunzio’s sight is gradually restored with the coming of spring and Easter. Yet much of the originality of this work lies not in a unifying theme or redemptive finale but in its tendency to offer up Preface ix disparate memories and conflicting sensations. Reminiscing about a dead friend, D’Annunzio notes that ‘‘there is a place in the soul where the river of darkness and the river of light flow together.’’ A hymn of loss and recovery, Notturno unfolds in a fluid space where hope and despair constantly converge: the book closes with an image of flames against a night sky, and of dying embers ready to be rekindled. The physical limit imposed by the size of the paper strips on which he writes lends an extraordinary lyrical quality to D’Annun- zio’s reflections, which together create what can only be defined as a prose poem, the first of its kind in Italian. The staccato phrases, with their narrative sparseness, are surprisingly versatile for ex- pressing grief, mutilated flesh, the chop of the water in the Venice lagoon. And they stand in stark contrast to the distinctive, highly wrought style of D’Annunzio’s earlier works. Heralded as a master- piece when it first appeared, this hauntingly beautiful and highly experimental composition helped inspire a new mode of writing, and it remains the most unsettling and timeless of all his prose works. The first complete English version of Notturno ever to be published, this volume offers a fresh and startling perspective on one of the most significant but later somewhat eclipsed figures of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European literature. D’Annunzio’s fame during his lifetime can hardly be exagger- ated. He published his first poetry at age sixteen, marking the beginning of a long and prolific literary career that also included novels, plays, and short stories. Sensual, psychological, and rich in lavish descriptions, his works earned him the informal title of