Nonsense on stilts : how to tell science from bunk PDF

Preview Nonsense on stilts : how to tell science from bunk

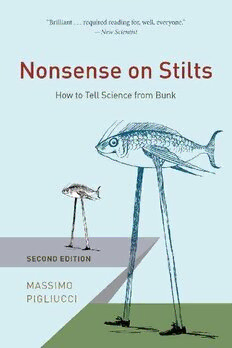

Nonsense on Stilts Nonsense on Stilts How to Tell Science from Bunk Second Edition massimo pigliucci the university of chicago press chicago and london The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010, 2018 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Originally published 2010 Second Edition 2018 Printed in the United States of America 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 49599- 6 (paper) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 49604- 7 (e- book) doi: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226496047.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pigliucci, Massimo, 1964– author. Title: Nonsense on stilts : how to tell science from bunk / Massimo Pigliucci. Description: Second edition. | Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018014122 | isbn 9780226495996 (pbk. : alk. paper) | isbn 9780226496047 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Pseudoscience—History. | Science—History. Classification: LCC qi72.5.p77 p54 2018 | ddc 001.9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014122 ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48- 1992 (Permanence of Paper). Contents Introduction Science versus Pseudoscience and the “Demarcation Problem” 1 chapter 1 Frustrating Conversations 6 chapter 2 Hard Science, Soft Science 17 chapter 3 Almost Science 41 chapter 4 Pseudoscience 73 chapter 5 Blame the Media? 107 chapter 6 Debates on Science: The Rise of Think Tanks and the Decline of Public Intellectuals 126 chapter 7 From Superstition to Natural Philosophy 156 chapter 8 From Natural Philosophy to Modern Science 177 chapter 9 The Science Wars I: Do We Trust Science Too Much? 202 chapter 10 The Science Wars II: Do We Trust Science Too Little? 221 chapter 11 The Problem and the (Possible) Cure: Scientism and Virtue Epistemology 246 chapter 12 Who’s Your Expert? 267 Conclusion So, What Is Science after All? 288 Notes 293 Index 315 introduction Science versus Pseudoscience and the “Demarcation Problem” “ The foundation of morality is to . . . give up pretending to believe that for which there is no evidence, and repeating unintelligible proposi- tions about this beyond the possibilities of knowledge.” So wrote Thomas Henry Huxley, who thought— in the tradition of writers and philosophers like David Hume and Thomas Paine— that we have a moral duty to dis- tinguish sense from nonsense. That is also why I wrote this book. Ac- cepting pseudoscientific untruths, or conversely, rejecting scientific truths, has consequences for all of us, psychologically, financially, and in terms of quality of life. Indeed, as we shall see, pseudoscience can literally kill people. The unstated assumption behind Huxley’s position is that we can tell the difference between sense and nonsense, and in the specific case that concerns us here, between good science and pseudoscience. As it turns out, this is not an easy task. Doing so requires an understanding of the nature and limits of science, of logical fallacies, of the psychology of be- lief, and even of politics and sociology. A search for such understanding constitutes the bulk of this book, but the journey should not end with its last page. Rather, I hope readers will use the chapters that follow as a springboard toward even more readings and discussions, to form a habit of questioning with an open mind and constantly demanding evidence for whatever assertion is being made by whatever self- professed authority— including, of course, yours truly. 2 introduction The starting point for our quest is what mid- twentieth- century philoso- pher of science Karl Popper famously called “the demarcation problem.” Popper wanted to know what distinguishes science from nonscience, including, but not limited to, pseudoscience. He sought to arrive at the essence of what it means to do science by contrasting it with activities that do not belong there. Popper rightly believed that members of the public— not just scientists or philosophers— need to understand and appreciate that distinction, because science is too powerful and important, and pseudoscience too common and damaging, for an open society to afford ignorance on the matter. Like Popper, I believe some insight into the problem might be gleaned by considering the differences between fields that are clearly scientific and others that just as clearly are not. We all know of perfectly good examples of science, say, physics or chemistry, and Popper identified some exem- plary instances of pseudoscience with which to compare them. Two that he considered in some detail are Marxist theories of history and Freudian psychoanalysis. The former is based on the idea that a key to understand- ing history is the ongoing economic struggle between classes, while the latter is built around the claim that unconscious sex drives generate psy- chological syndromes in adult human beings. The problem is, according to Popper, that those two ideas, rather para- doxically, explain things a little too well. Try as you may, there is no his- torical event that cannot be recast as the result of economic class struggle, and there is no psychological observation that cannot be interpreted as being caused by an unconscious obsession with sex. The two theories, in other words, are too broad, too flexible with respect to observations, to tell us anything interesting. If a theory purports to explain everything, then it is likely not explaining much at all. Popper claimed that theories like Freudianism and Marxism are unscientific because they are “unfal- sifiable.” A theory that is falsifiable can be proven wrong by some con- ceivable observation or experiment. For instance, if I said that adult dogs are quadrupedal (four- legged) animals, one could evaluate my theory by observing dogs and taking notes on whether they are quadrupeds or bi- peds (two- legged). The observations would settle the matter empirically. Either my statement is true or it isn’t, but it is a scientific statement— according to Popper— because it has the potential to be proven false by observations. Conversely, and perhaps counterintuitively, Popper thought that scien- tific theories can never be conclusively proven because there is always the science versus pseudoscience 3 possibility that new observations— hitherto unknown data— will falsify them. For instance, I could observe thousands of four- legged dogs and grow increasingly confident that my theory is right. But then I could turn a corner and see an adult two-l egged dog: there goes the theory, falsified by one negative result, regardless of how many positive confirmations I have recorded on my notepad. In this view of the difference between sci- ence and pseudoscience, then, science makes progress not by proving its theories right— because that’s impossible— but by eliminating an increas- ing number of wrong theories. Pseudoscience, however, does not make progress because its “theories” are so flexible. Pseudoscientific theories can accommodate any observation whatsoever, which means they do not actually have any explanatory teeth. Most philosophers today would still agree with Popper that we can learn about what science is by contrasting it with pseudoscience (and nonscience), but his notion that falsificationism is the definitive way to separate the two has been severely criticized. A moment of reflection re- veals that Popper’s solution is a bit too neat to work in the messiness of the real world. Consider again my example of the quadrupedal dogs. Suppose we do find a dog with only two legs, perhaps because of a congenital de- fect. Maybe our bipedal dog has even learned to move around by hopping on its two hind legs, like kangaroos do (in fact, such abnormal behavior has occasionally been observed in dogs and other normally quadrupedal mammals; just google “bipedal dog” to see some amusing examples). Ac- cording to Popper, we would have to reject the original statement— that dogs are quadrupeds— as false. But as any biologist, and simple common sense, would tell you, we would be foolish to do so. Dogs are quadrupeds, exceptions notwithstanding. The new observation requires, not that we reject the theory, but that we slightly modify our original statement and say that dogs are normally quadrupedal animals, though occasionally one can find specimens with developmental abnormalities that make them look and behave like bipeds. Similarly, philosophers agree that scientists do not (and should not) reject theories just because they initially fail to account for some observa- tion. Rather, they keep working at them to see why the data do not fit and how the theory might be modified in a sensible manner. Perhaps the new observations are exceptional and do not really challenge the core of a the- ory, or maybe the instruments used by scientists (whether sophisticated telescopes or simple gauges) are giving incorrect readings and need to be fixed— many things may give rise to discrepancies. This idea of modifying