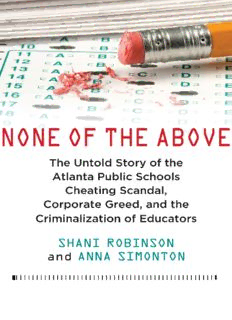

None of the Above: The Untold Story of the Atlanta Public Schools Cheating Scandal, Corporate Greed, and the Criminalization of Educators PDF

Preview None of the Above: The Untold Story of the Atlanta Public Schools Cheating Scandal, Corporate Greed, and the Criminalization of Educators

This book is dedicated to my wonderful son, Amari CONTENTS Prologue CHAPTER ONE: Hook, Line, and Sinker CHAPTER TWO: Finding My Way CHAPTER THREE: The Pot Calling the Kettle Black CHAPTER FOUR: Pushing the Envelope CHAPTER FIVE: The Darker the Night CHAPTER SIX: Between a Rock and a Hard Place CHAPTER SEVEN: Getting Cold CHAPTER EIGHT: Not the Brightest Bulb in the Box CHAPTER NINE: Speak of the Devil Epilogue Acknowledgments Notes Index PROLOGUE ON APRIL FOOL’S DAY IN 2015, I found myself in an unthinkable position. I was a thirty-year-old Teach for America alum, former counselor, newlywed mom-to- be. And I was a convicted felon facing twenty-five years in prison for something I didn’t do. For two years I had lived under the shadow of RICO. Otherwise known as the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, RICO was designed in the 1970s to target the American Mafia. But in 2013, RICO was applied to an unlikely group: the educators of Atlanta Public Schools. Including me. At issue were the district’s scores on a Georgia standardized test called the Criterion-Referenced Competency Test, or CRCT. In 2008, the Atlanta Journal- Constitution investigated suspiciously high score increases on CRCT retests in several school districts, including Atlanta. This prompted a state agency to conduct an audit of CRCT scores in 2009, analyzing the number of wrong-to- right erasures on students’ test booklets and finding a high likelihood that cheating had occurred in dozens of school districts across the state. Governor Sonny Perdue eventually ordered a special investigation to probe Atlanta and one other school district. When the dust settled, thirty-five employees of Atlanta Public Schools were indicted on RICO charges. All but one were black. Some faced prison terms of up to forty years. I never cheated. My first graders’ test scores didn’t even count toward “adequate yearly progress,” a set of benchmarks that the federal government required schools to meet under the No Child Left Behind Act. Nor did the scores count toward “targets,” another set of benchmarks imposed by the Atlanta Public Schools administration and board. But Perdue’s investigation was conducted like a witch hunt, or, as one attorney would later characterize it, “Shoot first and whatever you hit, call it the target.” Investigators used threats to get teachers to talk and offered immunity deals to those who told the “truth.” That often meant dragging educators in for multiple rounds of questioning until their stories changed to reflect what investigators believed the truth to be. This approach produced false accusations against two of my colleagues, me, and probably many more people. The trial that followed—the longest and most expensive in Georgia history— was a tragedy for Atlanta Public Schools, which had long served a majority- black student body under majority-black leadership in a city known as the Black Mecca, a place where black folks have thrived economically, politically, and culturally in spite of bitter oppression. It was a personal tragedy too, as I came from a family of teachers and social justice activists whose legacy I made it my life’s work to build upon. Growing up, I was always known as a “good girl.” It was what my mom, Beverly Robinson, expected of me because of the way she had been raised. Her mother, Dorothy, worked as a salad maker in the cafeteria at Peabody College— which later merged with Vanderbilt University—in Nashville, Tennessee. Dorothy raised my mother and her three sisters as a single parent with the income from her cafeteria job. They lived with Dorothy’s sisters and their children—ten people in a two-bedroom apartment. Dorothy did the best she could with what she had, and she filled the household with a lot of love and laughter. As a single parent, Dorothy was wary of the societal stigma surrounding her life. “I don’t want any attention called to us,” she often told her children. They had to act right, plus some. But she encouraged them too. She valued education and praised them for doing well in school. My mother raised me to care about education and respect, just like Dorothy taught her. On my dad’s side, I was instilled with a social and political consciousness. My dad, Jessie Robinson, was a big proponent of learning about African and African American history. He was mentored by a renowned black scholar, writer, and activist, Yosef Ben-Jochannan, who taught and inspired some of today’s foremost black intellectuals. “You have to know where you come from to know where you’re going,” he often told me. That’s the meaning of the Ghanian word sankofa, which is symbolized by a bird looking backward or by a swirling heart. I have a tattoo of the sankofa heart on my right ankle. My parents met in college and married in the 1980s. They moved to Decatur, a small city on the eastern edge of Atlanta, buying a home in an area that was predominantly black. Ours was the “neighborhood house.” On any given day, seven or so kids would come over to play games with my brother, Jamal, and me. My mom would cook huge meals to feed us all. Then she would sit us down to do our homework and tutor us in reading and math. Like many of the women in my family, my mother was a teacher. Her first teaching job in Georgia was in a town that was mostly white, Stone Mountain. The town was named for a huge mound of granite that had a sordid past. It was on top of Stone Mountain that the Ku Klux Klan was revived in 1915. Throughout the twentieth century, the Klan held rallies and cross-burnings there. Jamal and I attended Stone Mountain Elementary, where our mother taught. Getting in trouble was not an option, and we were expected to do our best to get straight A’s. When I was in sixth grade, I became the first black girl at Stone Mountain Elementary to win a Daughters of the American Revolution award. By the time I reached junior high, more black people were moving to Stone Mountain. My parents talked about moving there to be nearer our school. Our neighborhood in Decatur was having problems with drugs and crime. Sometimes we heard gunshots nearby. One time, a pregnant neighbor escaped a burglar and fled to our house. That was the last straw for my parents—their plan to move solidified. When I first saw it, I couldn’t believe the two-story white house with antebellum columns could become ours. At our old house, my brother and I shared a bedroom, but there we would have our own rooms, plus a family room and basement to play in. Down the road was a clubhouse with a pool. The neighborhood seemed so perfect that I couldn’t understand why so many houses had “for sale” signs in their yards. “It’s called white flight,” my mom explained. “That’s when black people move into a white neighborhood, but the white people don’t want to live with the black people, so they move out as fast as they can. It’s like birds that flock together. When one takes off they all follow.” We moved into our dream house, and as high school approached I enrolled in the Majority-to-Minority program, or M-to-M. In an effort to desegregate schools, the program allowed kids to transfer from a school where they were a racial majority to one where they were the minority. During my freshman year, my friends and I attended high schools that weren’t zoned for our neighborhood. We all caught the same school bus at six in the morning and rode it to a central location that we called “the shuttle.” When all the buses arrived, everyone switched to the bus going to their respective school. There were hundreds of black kids going to the white schools—but where were the white kids going to the black schools? I didn’t see many of them. My bus took me to Druid Hills High School in an affluent neighborhood on the northeast side of Atlanta. One of the city’s first suburbs, Druid Hills was full of lush, tree-lined streets and palatial homes built in the early twentieth century. The high school, also built during that time, looked like it was plucked from the pages of a fairy tale compared to some schools in my area that were known for not having any windows. At first I experienced culture shock. There had been few white people or non- black people of color at my old school and fewer subcultures—definitely none of the kids with purple Mohawks and goth makeup. I grew to love the diversity at Druid Hills High, so it frustrated me to see how segregation persisted. I was one of few black students in the National Honor Society, and there were hardly any of us in the Advanced Placement classes. In 1999, during my sophomore year, a lawsuit by a conservative legal group with an anti-affirmative-action agenda forced DeKalb County schools to end the M-to-M program. Those of us already in the program were allowed to continue, so I attended Druid Hills until I graduated in 2002. When I became embroiled in the Atlanta Public Schools cheating case, I often thought about these experiences as I tried to make sense of the situation at hand. Some of the social and political shifts that shaped my life had also set the stage for what became known as the “cheating scandal.” But the dominant narrative that developed about the scandal rarely acknowledged the bigger picture: federal policies that encouraged school systems to reward and punish educators based on student test scores; a growing movement, driven by corporate interests, to privatize education by demonizing public schools; and land speculation— correlated to new charter schools springing up—that was gentrifying black and brown neighborhoods across the country. In fact, Atlanta’s school board funded gentrification on the backs of students by handing millions of education dollars to private developers to build everything from luxury condos to office towers. Meanwhile, the state cut billions of dollars from its education budget, forcing schools to furlough teachers, increase class sizes, and eliminate enrichment programs. And at the same time that Perdue was persecuting educators, he used the questionable test scores to win a big federal grant. Yet no one involved in those real estate deals or policy decisions has been accused of “cheating the children,” the way that my colleagues and I were. Also missing from the public dialogue was a sense of historical perspective. How badly were children “cheated” by their teachers, relative to decades of racist policies and practices that had torn their families and communities apart? From urban renewal, to the drug war, to the dismantling of public housing— Atlanta might be the Black Mecca, but its black working class has been under attack for years. With the cheating scandal, some of the same people responsible for these attacks hypocritically declared cheating the worst thing to befall the children of Atlanta. Judge Jerry Baxter called it “the sickest thing that’s ever happened to this town,” apparently forgetting about things like slavery and Jim Crow. Perhaps most obscured is what actually went on in the courtroom. Compared to the sensationalized coverage of certain moments, like when educators were jailed, news media paid little attention to the numerous times the case was nearly dismissed, repeated calls for a mistrial, clear examples of prosecutorial misconduct, witnesses who perjured themselves, and some who recanted during testimony. The evidence against us was flimsy at best, but this case wasn’t tried on evidence. It was tried on emotion. People had strong reactions to the Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal because it’s true that there are real problems facing our public education system. Education is integral to a healthy democracy, so our concerns about education often illicit deeper anxieties about societal well-being. But the only way toward a public education that benefits all students, and society as a whole, entails addressing the root causes of the inequities and shortcomings that now exist. The Atlanta Public Schools cheating scandal was a distraction that deferred the real reckoning that we need to have. This book is my story, and it’s an attempt at that reckoning so that someday justice may truly be served.

Description: