Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition : cultural contexts in Monty Python PDF

Preview Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition : cultural contexts in Monty Python

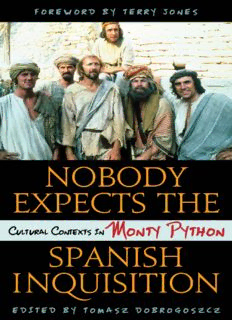

Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition Cultural Contexts in Monty Python Edited by Tomasz Dobrogoszcz Foreword by Terry Jones ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 FORBES BOULEVARD, SUITE 200, LANHAM, MARYLAND 20706 www.rowman.com 16 CARLISLE STREET, LONDON W1D 3BT, UNITED KINGDOM Copyright © 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition : cultural contexts in Monty Python / edited by Tomasz Dobrogoszcz ; foreword by Terry Jones. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-3736-0 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-3737-7 (ebook) 1. Monty Python (Comedy troupe) I. Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, 1970– editor. PN2599.5.T54N63 2014 791.45'028'0922–dc23 2014014377 TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America But remember, if you’ve enjoyed reading this book just half as much as we’ve enjoyed writing it, then we’ve enjoyed it twice as much as you. Acknowledgments The editor of the publication would like to express his most earnest thanks to Terry Jones for honoring the book with his foreword, as well as for his invaluable comments and kind words of encouragement. The editor’s gratitude also extends to Darl Larsen, a fountain-source of expert Python advice and warmhearted support. The inspiration for the idea of the book came from the Monty Python Conference held in Łódź, in October 2010. The efforts and enthusiasm of all its participants are genuinely appreciated. The editor is also deeply indebted to Andrew Tomlinson, whose most punctilious and ingenious copyediting allowed us to produce a more lucid and elegant text. Kevin Kern would like to extend sincerest thanks to Terry Jones for being so generous with his time in reading and responding to earlier drafts of this manuscript. Also reading an earlier draft were Dr. Christopher Stowe, Dr. Michael Levin, Dr. Martin Wainwright, and Christopher Garrett-Kern, and Kevin must thank them for their helpful suggestions. Kristie Kern, Kenton Kern, and J-C Jones-Kern also deserve credit for their patience and support in the course of this research. Last, Kevin must thank the University of Akron Department of History for generously providing funds to defray the cost of presenting this research in Lodz, Poland. The chapter by Katarzyna Małecka is a greatly revised and expanded version of the article that originally appeared in Studia Neofilologiczne VII (2011) under the title “‘Oh . . . and Jenkins . . . apparently your mother died this morning’: Monty Python’s Meaning of Death.” The research for the chapter by Miguel Ángel González Campos was funded by the Andalusian Regional Government (Proyectos de Excelencia de la Junta de Andalucía): Research Project P07-HUM-02507. Lastly, Prof. B. S. Gumby would like to express his most spontaneous and frank imbecility. spontaneous and frank imbecility. * All quotations from Monty Python’s Flying Circus are taken from the book The Complete Monty Python’s Flying Circus: All the Words, vol. 1 and vol. 2 (London: Methuen 1990). The references in parentheses use volume number, followed by page number (e.g., 1.123 is vol.1, page 123). All italicized parts in quotations are action description and appear in this form in the scripts book. The DVD version used for reference in this book is: Monty Python’s Flying Circus. The Complete Box Set. Dir. Ian McNaughton. Perf. Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin. 1969–1974. Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, 2008. All quotations from Monty Python feature films are taken from their DVD versions, with further assistance of the Internet site www.montypython.net (perhaps the most reliable and comprehensive site featuring Monty Python scripts). The DVD versions of feature films used for reference in this book are: Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Dir. Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones. Perf. Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin. 1974. Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment, 2003. Monty Python’s Life of Brian. Dir. Terry Jones. Perf. Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin. 1979. The Criterion Collection, 1999. Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. Dir. Terry Jones. Perf. Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin. 1983. Universal Studios Home Video, 1997. All quotations from the German television show Monty Python Fliegender Zirkus are taken from the DVD version: Monty Python’s Fliegender Zirkus. Dir. Ian McNaughton. Perf. Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, Michael Palin. 1971–72. Rainbow Entertainment, 2002. The preceding sources are not mentioned in references of The preceding sources are not mentioned in references of particular chapters. Foreword I never realized Monty Python was taken so seriously in the academic world, until I learnt of the Monty Python Conference taking place in Łódź (pronounced, I believe, “Wodge”) in Poland, 28–29th October 2010. These chapters are the residue of that conference, and I must say I find them fascinating! Well I would, wouldn’t I? It’s all about what I, and a few friends, were doing in our late twenties and thirties. And we still remain friends, after all this time—doing nothing together for over thirty years. Maybe that’s why we’re still friends. I have to confess to having a terrible memory. So it’s really great to be referred back to some of the things we’ve done in the past—like Edyta Lorek-Jezińska’s “The Corpse and Cannibalism in Monty Python’s Flying Circus Sketches”—I’d totally forgotten about the life-boat sketch (“I’d rather eat Johnson”). Or Eric Idle playing with the Bonzo Dog Do Da Band in Do Not Adjust Your Set in Richard Mills’ “Eric Idle and the Counter-Culture.” I’d also totally forgotten that. And where else can you find Monty Python sketches referenced to Bakhtin, Foucault, Freud, Shakespeare, and Swift? Katarzyna Małecka, in “Death and the Denial of Death in the Works of Monty Python,” starts from the premise that psychologists claim that we tend to deny the reality of our own death, “but can conceive our neighbor’s death, . . . [which] only supports our unconscious belief in our own immortality and allows us—in the privacy and secrecy of our unconscious mind— to rejoice that it is ‘the next guy, not me.’” She concludes: “Thus, being struck on the head with a large axe while trying ‘to recite the Bible in one second’ and being able to say only ‘In the . . .’ is not as far-fetched as it may seem, reminding us yet again that the beginning and end might be nearer each other than we expect.” She obviously has a sense of humor. There are real insights too in this book. Katarzyna Poloczek, writing about “The Representation of the Woman’s Body in Monty Python’s Meaning of Life,” claims: “It is argued here that despite the seemingly surreal content, the aforementioned film [The Meaning of Life] aptly addresses vital gender issues, frequently exhibiting a poignant critique of patriarchal society.” And you know, it does! When I started the chapter I was afraid that she was going to tear us to shreds. But, of course, in the childbirth scene at the start of the film “the experience of childbirth is depicted as a purely medical procedure, controlled entirely by male doctors, the role of a woman in labor is made virtually redundant.” I guess we knew what we were writing about when we wrote it, but I don’t think we knew that if “the Pythons had employed one of their own group members to act out the scene, its mock-documentary ‘realism’ would be destroyed, as the audience’s attention would be focused on the male performer, and not on the surrounding milieu.” We just did it instinctively. Stephen Butler and Wojciech Klepuszewski, in their chapter “Monty Python and the Flying Feast of Fools,” link the bishop sketch, where the bishop becomes an avengers-type hero, to the subverted role of the bishop in the Feast of Fools, “where the Bishop, would be replaced by a Bishop of Fools, usually a child elected by the congregation.” They conclude: “The irony of this skit is that the Pythons themselves would face an equally threatening bishop, the Bishop of Southwark, ten years later in a television debate on the blasphemy of The Life of Brian.” Things I’d never connected before. They conclude: “Rather than seek to transform the existing order, the Feast’s job was to ensure that the hierarchies would remain in place. Whether the same is true of Python’s comedy is difficult to state with any degree of certainty, mainly due to the conflicting statements of each of the members.” And it’s true. I think that we just jumped onto the bandwagon of critiquing authority, which was all the rage in the late sixties. I don’t think we ever thought our little show was going to alter things, but I do think Monty Python was a synthesis of all our ideas. Justyna Stępień claims that the “TV programs contain well- used patterns which viewers would never normally recognize as kitsch” and goes on to prove that “the retro kitsch used by the

Description: